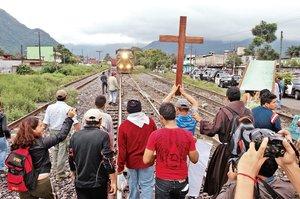

About a week and a half ago, a group of activists and immigrants began a trek by car, bus, and train from various locations in Guatemala and Mexico’s southern border (with Guatemala and Belize) to Mexico City, demanding that the Mexican government put an end to the horrific violence inflicted on undocumented Central Americans passing through Mexico, particularly in the gulf-coast states of Tabasco, Veracruz, and Tamaulipas.

The group was composed of human rights activists and family members of the newly “disappeared.” There were anguished mothers and fathers carrying portraits of their missing sons and daughters; angry brothers and sisters demanding justice and respect for countrymen seeking what they hoped would be a better life. The mothers, in particular, looked, talked, and mourned like any other “mothers of the disappeared”—decades ago in Argentina and Chile; more recently in Guatemala and El Salvador—only this time their sons and daughters were not disappeared for being radical activists, but for being undocumented migrants trying to make their way northward.

The group was composed of human rights activists and family members of the newly “disappeared.” There were anguished mothers and fathers carrying portraits of their missing sons and daughters; angry brothers and sisters demanding justice and respect for countrymen seeking what they hoped would be a better life. The mothers, in particular, looked, talked, and mourned like any other “mothers of the disappeared”—decades ago in Argentina and Chile; more recently in Guatemala and El Salvador—only this time their sons and daughters were not disappeared for being radical activists, but for being undocumented migrants trying to make their way northward.

Their arrival in Mexico City is captured in a moving three-and-a-half-minute video shot by filmmaker Alberto Torres for the Mexican daily paper El Universal. (Video—in Spanish—below).

The march was organized to pay homage to those who had disappeared into forced participation in criminal gangs, into people-trafficking networks, into common graves, and to demand that federal deputies pass an “authentic” migratory law that would decriminalize undocumented migrants on their way to the U.S. border, and protect them from the predatory acts of criminal gangs and extortionists.

Members of Mexico’s National Commission of Human Rights (CNDH) accompanied the caravan—called Step-by-Step Toward Peace—along the traditional migrant routes on the gulf coast, providing a degree of protection for the migrants and the workers in the network of migrant refuges. When the caravan reached Veracruz, it turned inland, to the cities of Puebla and Mexico City

One of the prominent defenders of human rights, among the 600 or so marchers, was a radical priest from Puebla named Alejandro Solalinde, who invited some of the victimizers, the brutal, infamous Zetas to, join the march for peace. He even—in the name of Mexico—asked for their pardon for being themselves victimized (damnificados) by a corrupt, neoliberal, failing government.

Unlike the pacifist marches led by the poet-turned-activist Javier Sicilia, this one was escorted part of the way by armed Oaxacan police officers, recruited following threats received by Father Solalinde’s parish. In Puebla, the activist priest was briefly arrested, his escorts sent home, and his parish searched for arms. But the caravan continued.

The mobilization of this small caravan for peace allows us a glimpse of a small corner of the struggle against the counterproductive, U.S.-sponsored war against organized crime and drug trafficking. It also allows us to see a small corner of the struggle against the equally counterproductive war against undocumented migration. These struggles leave plenty of room for solidarity.

El Universal TV - Demandan a México detener asesinatos a migrantes

Did you find this useful? Donate to NACLA