Report

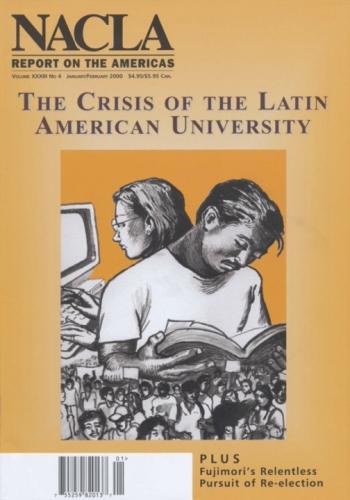

The technological advances of the twenty-first century will transform higher education as we know it. Latin American public higher education will be no exception.

"It's a national disgrace! There's money for Pinochet and not for education!" With this angry message, the students of Santiago's Metropolitan Technological University took to the streets in April 1999 to denounce the Chilean government's generous financing of General Augusto Pinochet's legal defense while it fails to provide sufficient funding for public universities.[1]

Carlos Ivan Degregori and Javier Avila Molero

The first university in Peru, San Marcos National University, was founded in 1551, just a few years after the arrival of the Spanish. As an institution it was fundamentally directed toward the training and education of priests and the colonial creole aristocracy, with professors holding static, life-long positions, poor support for students, and little in the way of solid scientific formation.

One cannot talk about the future of education without talking about the future of work. There are immediate questions of unemployment, the dwindling number of industrial workers, automation and robotization, even the massive redefinition of jobs.

A few brief moments of institutional splendor aside, the history of the Latin American university is a history of crisis. Indeed, because the words "crisis" and "university" go hand in hand in Latin America, and because the deep problems in which the university system now finds itself are so complex and vary so much from institution to institution, it is difficult to talk about the "crisis" in the singular.

On Friday, October 29, just a few days before Halloween and the Day of the Dead, Mexico's then-Minister of the Interior, Francisco Labastida —now his party's presidential candidate—disguised himself as Mary W. Shelley and rewrote the story of Baron von Frankenstein and his out-of-control monster. The literary pretentions of this loyal stalwart of the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) were not without political motivation.