This article originally appeared in the Winter 2013 issue "Latino New York"

In the mid-1970s the New York media alerted the public to a “Latin Boom” in the big city. Back then it was the salsa craze, the emergence of a new wave of politicians and activists, and the surpassing of the one million threshold in the Latino population. Since then, each passing decade has brought on new assertions of a breakthrough moment. Four decades and over a million Latinos later, we seem to be on the verge of another boom.

Booms imply a temporary burst in activity, as in the high-tech sector or housing market of recent years. Those booms led to crashing busts. But the growing Hispanic presence reflects a long-term steady rise. The population may eventually reach a plateau, but there will not be a bust. There is no going back as new arrivals keep coming, and as successive generations of native Latinos make the city their home. In 1950, Latinos comprised less than 5% of the total population and by 2010 they were almost 30%: surely, one of the most significant changes in post-WWII New York.

The growing presence and accompanying changes are manifested in several ways: population size, composition of Latino sub-groups, residential patterns, place of birth, and other important data such as education and language use.1

By 2010, Latinos numbered 2.4 million, 29% of the city’s population. In 1990, by contrast, they were 1.7 million representing 24%. Puerto Ricans were the largest single group during the last century. But the numbers appear to be rapidly changing. The projections of the demographers indicate that the next decennial census will register Dominicans as the largest group (some observers think they already are). Some years later, Mexicans are expected to attain that distinction. (See Gonzales, this report.)

Predictions of this sort are subject to many factors that may throw current trends off track. We do not know, for example, how the new immigration legislation, if indeed there is any reform, will affect the future. Recent reports show that the net migration of Mexicans to the United States is no longer growing. We do not know what the impact of the Great Recession will be on others contemplating a move here. The virtual collapse of the Puerto Rican economy has led to a new wave of migrants from the island, unhampered by migration restrictions. Much attention has been directed at Florida, where rising numbers of Boricuas contributed to Obama’s victory there in 2012, and where Disney World has become a major employer of distressed islanders. But Puerto Ricans are fleeing to New York and elsewhere in the northeast corridor too. (See Morales, this report.)

In the Dominican Republic, hard times have followed upon the heady economic expansion of the early 2000s, encouraging new emigration. Immigrants from that island seem to face less cumbersome barriers to entry than those trying to cross the southwest United States, partly because of the option of going through Puerto Rico where border surveillance is less effective.

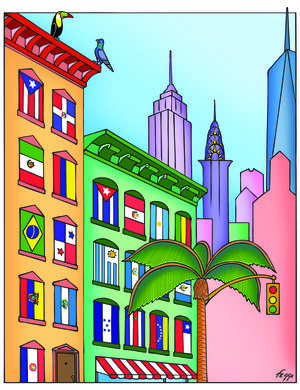

The “Big Three”—Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, and Mexicans—comprise some 70% of all New York Latinos. Yet other nationalities—Ecuadorans, Colombians, and Central Americans—figure notably in the mosaic of Spanish-speaking groups. No other city in the country displays such heterogeneity of Hispanic-origin peoples.

Whatever one may speculate about the shifting shares of Latino sub-populations it is clear that the long arc of population growth will continue unabated. This is because Latino numbers will be driven primarily by the New York-born (or U.S.-born) and not by immigrants. The former are less subject to the sueño del retorno (the dream of returning) and more likely to remain long-term and start families here. Another way of saying this is that Latinos are younger and are having more babies than the average New Yorker. Though they make up 29% of the city, they are 36% of the city’s 18-and-under population. The share of the youth sector for other groups is significantly less: 25% for non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks, and 11% for Asians. Latina fertility rates are also higher than that of other racial/ethnic groups.

With growth comes dispersion. There was a time, in the early twentieth century, when Latinos found themselves concentrated in a handful of city neighborhoods: East Harlem, the Lower East Side, Morrisania in the South Bronx, and Williamsburg and Red Hook in Brooklyn. Now they have cast a much wider net. Since the 1970s whole new areas have been “colonized.” Washington Heights and Inwood in Upper Manhattan have become the core community and political base for Dominicans. Initially, Mexicans gravitated toward East Harlem and to Puerto Rican enclaves elsewhere in Manhattan and Brooklyn. More recently they have settled in various parts of the Bronx. Ecuadorans and Colombians have made parts of Queens (Jackson Heights, Elmhurst, Corona) their own.

There is a deep association of Puerto Ricans with El Barrio (East Harlem) and of Dominicans with Washington Heights, both areas located in the borough of Manhattan. Yet overall, 40% of Boricuas and 41% of Dominicans reside in the Bronx. Mexicans have yet to establish a central geographic home. Since the 1980s their migration and settlement experience is the story of significant spatial dispersion throughout the boroughs.2 Ecuadorans and Colombians are highly concentrated in the borough of Queens. Four out of five Latinos now live in the boroughs of the Bronx, Queens, and Brooklyn. In mid-twentieth century the great majority lived in Manhattan and the South Bronx, a subway ride away from the garment center and other light manufacturing districts. (See Figueroa, this report.)

*

Second only to the demographers in their attention to Latino population trends are the politicians. In the recent race for the mayoralty of the city—which was bereft of a serious Latino contender for any citywide office—candidates proclaimed their appreciation of Latin cuisine and music, and the Spanish language. In elections past, consultants could advise their clients to not trouble themselves over Hispanic voters. They were deemed an insignificant group in the grand scheme of things. But all that has changed in the past years. Today more than three quarters of Latinos are citizens and they constitute nearly 25% of the city’s eligible voters. In 1990 they were only 18% of the voting population. Changing population shares have led to shifts within the Latino electorate. Between 1990 and 2010 Puerto Ricans declined from 70% to 44% of all Latino voters; Dominicans increased their representation from 10% to 23%.

Latinos have engaged in a broad range of organizing and advocacy efforts, formal and informal. There has been an increase in office-holders on the City Council, with Dominican representation adding to the traditional Puerto Rican presence. Most recently, the Democratic Primary assured for the first time, the addition of a Mexican-American to the City Council. Despite the unabashedly pro-Wall Street orientation of the Bloomberg years, New York City is still a union town. Several initiatives have been undertaken to organize restaurant, domestic, and healthcare workers, and to increase the standard of living for the already-unionized sectors (building maintenance and retail workers). Living wage campaigns have seen the active participation of Latinos, as has the effort to unionize car wash workers, los washeros.

The typical Hispanic employee earns a living in the service sector, an amalgam of mostly low-paying jobs in areas such as food service, homecare health, personal service, and maintenance. Older Puerto Rican and Dominican workers tend to be in production, compared to younger workers (especially women) who are in sales.3 Progression into higher-paying professional and management occupations comes primarily with generational change, English-language proficiency, and greater educational attainment. In other words it takes considerable time for upward mobility to be perceived at the collective level, though there has been progress in the case of Puerto Rican and Dominican women. Mexicans, more recent arrivals and generally non-citizens, are less represented in professional and management positions compared to other Latinos. Unlike other Latino groups, for whom service jobs are mainly taken by women, both male and female Mexicans are heavily concentrated in the services sector. (See Figueroa, this report.)

We can summarize Latino socio-economic patterns based on the experience of the past few decades. First generation Latinos work intensively in low-wage jobs, while their native-born children split among three pathways: (1) those who move up into professional positions through higher education, (2) those who gain access to stable, often unionized, jobs providing somewhat decent incomes, and (3) those who get stuck in poverty jobs or are sidelined from the formal labor market altogether. The last group, some 25% to 30% of Latino households, represents the hardest hit by the wrenching economic difficulties of recent years. Latino and African American poverty is between double and three times the level of white New Yorkers'.

*

New York’s Latinos have much in common with their co-ethnics elsewhere in U.S. urban centers. Generally confined to the lower strata of the job market, they have to be content with low-wage work that offers few opportunities for occupational mobility. Unscrupulous employers withhold earnings, ignore occupational health standards, and abstain from providing health care coverage. A certain class of business owner thrives on the vulnerability of immigrants, legal and undocumented, to succeed.

Workers compensate by piecing together multiple employment situations. This results in higher than average labor force participation rates and in higher than average hours worked per week. The real level of labor activity is unknown due to the extent of the informal economy.

The fruits of their labor are not all kept locally. Earnings are frequently sent back to Dominican, Mexican, and Central American hometowns, where families and communities are dependent on income from abroad. Remittances of immigrant workers have replaced U.S. foreign aid as the main external assistance for several poor countries south of our border.

As elsewhere, New York’s Latinos experience transnational lives. They communicate with families back home and visit when they can. The Dominican and Mexican consulates participate in community development projects and interchange programs of youth. The Puerto Rican political parties fundraise for their candidates and lobby locals on the island’s future political status. (For an interesting Mexican example of the transnational life, see Santos-Briones, this report.)

A few characteristics distinguish them from Latinos in other cities. In places such as Los Angeles, San Antonio, Denver, Houston, and Miami, specific groups (Cubans in the last case) hold a dominant influence. In Washington D.C. we see the emergence of Central American strength, primarily Salvadoran. New York is increasingly an incubator of heterogeneous Latino power, as alluded to in the designation of the “Big Three."

Unlike other locales, New York displays a larger component of Caribbean-origin Latinos.

Between the two, Puerto Ricans and Dominicans constitute a majority of the Latino population. (There is also a declining, but still palpable Cuban presence.) But they have not always agreed when the time has come to join forces over local issues. During Congressman Charles Rangel’s 2012 reelection bid, most Puerto Ricans sided with the African American incumbent against challenger State Senator Adriano Espaillat, a Dominican based in Washington Heights. (See Morales, this report.)

The Caribbean background is also expressed in racial terms. An important aspect of the New York Puerto Rican experience was the assertion of an identity that affirmed their partially African origins. This became a prominent perspective of Boricua activists during the political movements of the 1960s and 1970s. Scholars have begun to trace this history back to the pre-World War II era, when Puerto Ricans were faced with a choice: identify as immigrants embarking on a path toward assimilation, or as a racial minority struggling for first-class citizenship.4 Ultimately, the decision by the politically active leadership was for the latter path. This posture, along with concrete factors such as residential proximity and similar occupational location in the public sector, opened the path toward a relationship with African Americans that has favored collaboration over conflict ever since. The evolution of Dominicans’ sense of racial/ethnic identity, especially across generations, is a major interest among scholars inside and outside the community.

Another notable difference is the preponderance of Mexican immigration from the Mixteca region. No other city has attracted nearly the numbers of people from the city of Puebla, for example. What these factors might signify for future evolution of the New York Latino community is rich material for further discussion and research.

*

As Latino communities undergo growth and change, so too has the city. No one doubts Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s impact on New York since coming to power soon after the 9/11 attacks. But there is sharp debate over whether this change has been for the better or worse. Yes, he has beautified and expanded parklands, reduced carbon emissions and pollution, brought down violent crime, and argued sternly for gun control. But these accomplishments are in keeping with his vision of the city as a “luxury product” to be consumed by the wealthy. This was his famous comment early in his administration, predating Mitt Romney’s criticism of the “47 percent.” These improvements have been a boon to the tourist and hospitality industries, and to the financial and real estate sectors. Bloomberg’s project has been to demonstrate that trickle-down urbanism can work for the world-class city.

But one needs to glance past the glossy exterior of Manhattan’s skyline and Times Square’s neon brilliance, beyond the pockets of high-rise development and gentrified enclaves, to appreciate the deeper changes transforming the city.

The Occupy Wall Street movement lambasted the ballooning wealth of the very rich. Their rhetoric was not off the mark. During Bloomberg’s tenure, the “one percent” increased its share of total income from 27% to almost 40%. Even at the height of the Reagan-inspired era of “irrational exuberance,” leading up to the Wall Street crash of 1987, the super-rich took in only 15%.5

Stockbrokers, hedge fund owners, and others in the securities industry have done very well during the Bloomberg years. Their average salary ($362,900 in 2011) was higher than before the financial crisis of 2008-2009, and more than five times the average in the rest of the city’s private sector. As a share of private sector wages, the securities industry grew from 21% when Bloomberg began, to 28% early in his second term, while never accounting for more than 6% of private sector jobs.

In contrast to the stagnating incomes of average New Yorkers during the first decade of the millennium, the median family incomes of families in neighborhoods where financial industry personnel reside (e.g., TriBeCa, Upper East Side) rose an average of 55%.

The so-called “recovery” was not nearly so bountiful for the rest of the city. The poverty rate, at about 20%, has remained unchanged for a decade. Although the number of jobs has risen with the overall growing population, currently the unemployment rate stands at 8.6%, higher than the national average and much higher than when Bloomberg took over. Real wages have declined, as they have across the nation.

Latinos have particular cause for concern in an area where the mayor has direct control: hiring in New York City government. Public sector jobs are among the few arenas in which decent incomes can be earned along with health insurance and pensions (and even here Bloomberg has forced employees to work under expired contracts, passing this headache onto the next mayor). According to a report from the National Institute for Latino Policy (NiLP), Latinos are severely underrepresented in the municipal labor force. Although comprising 25% of the overall civilian labor force, only 18.3% of government employees during the Bloomberg administration in 2011 were Latinos. The hiring gap was especially obvious in the upper echelons of city government. Only one of 11 deputy mayors and four of 80 heads of agencies and offices were Latinos.6

More generally, Bloomberg has consistently opposed basic tenets of economic justice. As Mark Green, a Democrat and former New York City Public Advocate, has voiced: “Can anyone think of a contest between capital and labor—living wage, minimum wage, sick leave, progressive taxes—when Mr. Bloomberg sided with average families?”

For Latino New Yorkers struggling to attain the status of even the average family, the post-Bloomberg years can bring more of the same, or hopefully usher in an era of social and economic justice. This will require self-organization and grassroots activism, creative strategizing and a commitment to cooperation and solidarity—among Latinos and across ethnic lines. We hope this issue of the NACLA Report identifies perspectives and resources that can contribute to future progress.

1. Unless otherwise noted, the empirical data in this article come from reports issued by the Latino Data Project of the Center for Latin American, Caribbean and Latino Studies, (CLACLS), City University of New York. The studies were largely based on U.S. Census studies and were overseen by Dr. Laird W. Bergad, Center Director. All reports can be accessed at http://web.gc.cuny.edu/lastudies/.

2. Robert C. Smith, “Mexicans in New York,” in G. Haslip-Viera and S. Baver, eds. Latinos in New York: Communities in Transition (Notre Dame, IN: Notre Dame University Press, 1996).

3. Occupational trends are reported in S. Ruszczyk, “How do Latino Groups Fare in a Changing Economy,” CLACLS, Report 48, November 2012.

4. Lorrin Thomas, Puerto Rican Citizen (Chicago: U. of Chicago Press, 2010).

5. Data on earnings, income and poverty are drawn from New York Times, Metropolitan section, August 18, 2013; articles by Ginia Bellafante, Jim Dwyer, and Patrick McGeehan.

6. Angelo Falcon, NiLP, “Latinos in NYC Government: A Bloomberg Diversity Cover-up?” July 8, 2013.

Andrés Torres is Distinguished Lecturer in the Dept. of Latin American, Latino and Puerto Rican Studies at Lehman College, CUNY. His most recent book is Signing in Puerto Rican: A Hearing Son and His Deaf Family.

Read the rest of NACLA's Winter 2013 issue: "Latino New York"