Join us this Thursday, October 20, from 6:30-9:00 PM at the Jerry H. Labowitz Theatre for the Performing Arts, Gallatin School (1 Washington Place, New York, NY) to learn more about the situation facing child refugees from Central America, and help us to galvanize public opinion about the barriers they are facing in rebuilding their lives.

Sixty million people around the world became refugees in the year 2015, half of whom were children. While the majority were Syrian refugees, who have been highly visible with good reason, U.S. Border Patrol statistics suggest that more than 120,000 unaccompanied children (and an almost equal number of families with children—primarily single mothers) have also become de facto refugees over the past two and a half years. Nearly all of these individuals have made a very dangerous journey from Central America in an attempt to find safety in the United States.

The International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY) is one of several non-governmental organizations that has heeded the call to respond to this grave situation. IBBY is a global NGO, founded in 1952, that conducts international projects in areas impacted by natural disasters and in conflict zones. In 2008, for example, IBBY built two libraries in Gaza, both of which were destroyed in the recent war but have since been rebuilt. When IBBY visited the site in 2013, during the Egyptian Spring, many parents told us that their children attended the library every day after school, and explained the remarkable psychological impact that reading had on their children’s ability to sleep, learn, and find a sense of calm.

IBBY’s “Children in Crisis” program has also taken place in Lebanon, where IBBY has worked with Syrian refugees, using books to help children to work through conflict and develop empathy skills; in Iran, where IBBY has helped Afghan refugee children to prepare for entry into the formal educational system; and in Aghanistan, where IBBY has supported eight “bibliobuses,” run adults trained in reading promotion, storytelling and reading aloud, and in Pakistan, where IBBY has been commissioned to build 500 school libraries.

IBBY also launches projects following natural disasters—for example, ongoing programming in Indonesia and Japan following tsunamis, a bibliotherapy project in Venezuela following landslides, and in Peru, Chile, Ecuador, and Haiti following devastating earthquakes. In-country IBBY member volunteers set up points for children to practice reading aloud on a regular basis. Sometimes this has meant recreating libraries in the rubble, on the backs of motorcycles, or on small trucks. Essential to the success of all these interventions is the presence of a mediator, an adult, who is present consistently, respectful, knowledgeable, and caring.

In response to the arrival of tens of thousands of child refugees fleeing Central America, Known as the “border surge” IBBY travelled to the U.S.-Mexico border in 2015, as part of a delegation aimed at bringing the power of reading to the thousands of mostly Central American children who have fled violence and organized criminal actors in Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala. These children have faced shocking levels of trauma, both precipitating their journey and along the dangerous path to the United States. According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, 57 percent of Honduran children, and 38 percent of Guatemalan children, should be eligible for international protection as “refugees,” given the circumstances of their departure from their home countries. But despite the fact that children from Central America are facing imminent danger in the countries in which they live, most have found it almost impossible to be accepted in the U.S. as legal refugees..In 2014 and 2015, just over 3% of unaccompanied child minors had succeeded in obtaining refugee status and only 30% had been given temporary relief, according to the Migration Policy Institute (MPI). And the backlogs present another problem – as of January 2016, 69% of families with children and 60% of unaccompanied children still have pending immigration decisions.

What’s more, very few children have any legal support when and if they appear before a judge. While only one in ten children with legal representation is deported, half of those who don’t are deported, according to the New York Times. While in South Texas, we met with an organization comprised of pro-bono lawyers who explain the refugee process to the children. But they do not accompany the children as they move on. For the vast majority this is the only contact they will have with a lawyer in the refugee process. Very few are able to obtain free legal assistance. Pro-bono services, where they exist, are overwhelmed with potential clients, and in many places they do not exist. The federal government has stated it has no legal obligation to provide legal services.

As of July 2016, approximately 40,000 children have either been deported or are facing orders of deportation. The situation in Mexico—the country through which nearly every Central American refugee must travel—is scarcely better. The number of children detained by Mexican officials increased by 75% between July 2014 and 2015, largely due to the implementation of Plan Frontera Sur—a program funded by the U.S. and Mexico to increase border security on Mexico’s Southern Border. The program has also led to increased violence against migrants and asylum-seekers in transit through the country.

Various NGOs, both in the U.S. and Latin America have tried to respond to the situation facing Central America’s child refugees. IBBY responded in the way that our expertise allowed—through literacy and bibliotherapy. The two-day fact-finding delegation that our organization conducted in 2015 included IBBY members from the United States and Mexico, as well as colleagues from REFORMA (the National Association to Promote Library and Information Services to Latinos and the Spanish-Speaking), an organization of librarians from the United States.

When we arrived in the Rio Grande Valley in South Texas, we found that little has changed since photographs of children and families in detention centers leaked during the so-called border surge of the summer of 2014. Unaccompanied children usually present themselves at the border, claiming asylum. They are then detained in U.S. Customs and Border Protection facilities. We visited the inside of one such location, where children were held in a gym-like space in floor to ceiling cages with televisions for viewing and space blankets for warmth. According to agents we spoke with, the detainees are kept here for no more than 24 hours. Some children are immediately deported, while others are placed in nonprofit group home facilities. We asked repeatedly during our visit what criteria determined these decisions. We never received a reply to this very pertinent question and concluded that these are likely highly subjective.

We also visited one of the group homes where children stay for anywhere between a few weeks to several months while they await placement with a relative in the United States, regardless of the relative’s legal status. While this is the best option in terms of family reunification, it also opens the children to the threat of further abandonment if their guardians are to be deported. In the meantime, according to our interviews, children are fed, provided access to some kind of schooling, health care, and allowed to call their families in their home countries and at their intended destinations. Schooling, however well-intentioned, rarely seemed well-adapted for the children’s ages or reading levels. Consider, for example, though many of the children we saw were illiterate or barely literate, they were assigned to read Don Quixote.

Until very recently, once the children left these facilities, often heading off alone on a bus across the U.S. to meet a family member who is willing to take them in, the only organization that monitored their ongoing cases were various branches of the Department of Homeland Security. Some of the children processed between 2014 and 2015 were sent to places that had not been properly assessed, resulting in instances of exploitation and sexual abuse. The Department of Health and Human Services is supposed to have overall responsibility for the children, but they failed to provide regular home visits or even check in on the children’s well-being.

During our delegation’s visit, we were not permitted to talk to children individually. However, we were allowed to visit a detention facility— the name of which we were asked to keep anonymous— and to address the children as a group. Our goal was to connect them with a public library at their eventual destination that could help them access services, information, and basic assistance for getting settled. In talking with the children, what we found was a group that had faced serious traumas and abuses—some of the girls had been raped, while others were in isolation because they had contracted tuberculosis. Language barriers – a significant proportion of the Guatemalans only spoke Mayan languages – presented another challenge for their potential representation in court. (While Spanish is spoken widely at the border there are virtually no services available for non-Spanish speaking children or women.) And because of either interrupted schooling or the absence of it altogether, most had very low reading levels.

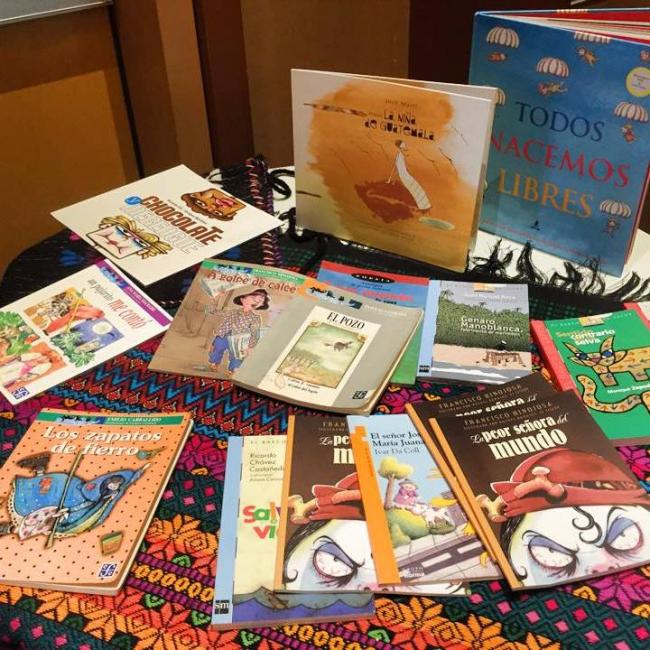

Though U.S. Customs and Border Protection has agreed to accept donations of books for the children, they will not allow anyone—no matter their qualifications—to come to the detention facilities to conduct any kind of ongoing bibliotherapy sessions—something that IBBY and its partner organizations specialize in. To get around this, we determined that each child should be given both a book and information urging them to go to their local public library when they arrived at their destination. In many cases, librarians, particularly bilingual REFORMA librarians, can help fulfill the role of mediator and guide that these children require.

Following our trip, IBBY and REFORMA have actively fundraised and donated high-quality, bilingual books to child refugees; our organizations have also provided information urging the children to visit their local library as they leave facilities to get plugged into our growing network of activist librarians. REFORMA has even produced a tool kit for libraries, giving them suggestions on how to work with these populations in those areas where they are most likely to end up. And the American Library Association and its various affiliates have donated funds and held webinars for its members in the primary locations where these children are going. Members of REFORMA, children’s librarians, and IBBY members are now working on the difficult task of following up with the children once they have reached their destination.

Among other things, IBBY’s border delegation made one thing very clear: The situation that has driven Central American children to become refugees is not the product of unseen forces in faraway countries. It is the direct result of the past seventy years of U.S. foreign policy, the persistent demand for drugs in the U.S. and the failed war on drugs. Many of the root causes for violence in Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras today derive from the armed struggles during the Cold War, so heavily funded by the United States. In Guatemala, very few of the steps outlined in the Peace Accords were enacted. In El Salvador, intra gang warfare has entered the social vacuum that the Salvadoran state failed to fill after the country’s long civil war. And the 2009 coup against Manuel Zelaya in Honduras exacerbated the country’s already rising homicide rate. In general, high levels of inequality and social injustice persist in Central America.

Even where governments, and especially civil society, struggle to assist those children who are the pawns in this unsettling situation, it is virtually impossible to protect them. Families give what they have, and send their children alone into danger, but only because they have no alternative. To return them once they have made the extraordinarily difficult journey to Mexico and on to the United States is, in this author’s opinion, a crime against humanity. These children are our joint responsibility. They need protection. They need lawyers. They need advocates. They need to be educated. They need access to books and librarians so they can receive the great benefits of becoming readers. Most critically, perhaps, they need the opportunity to live safely at their destinations so that they can have an opportunity for a decent life.

Patricia Aldana is a Guatemalan who came to Canada and became a citizen in 1971. She was the founder and Publisher of Groundwood Books, a leading publisher of books for children, a former President of IBBY and now President of the IBBY Foundation. She was named to the Order of Canada in 2010.