Remember that old song from the children’s television show Sesame Street that opens by rhetorically asking, “Who are the people in your neighborhood?”, the one that responds with the words “the people you meet each day?” Among the non-threatening types of people the song references are a baker, teacher, dentist, and grocer. Imagine what an ominous song it would be if one of the “people you meet each day” were a U.S. Border Patrol agent.

While the Border Patrol has long stalked neighborhoods in the U.S. Southwest, the agency has now established a threatening presence in the U.S.-Canada borderlands as well, most notably in little towns and small cities in Washington State. That it has done so speaks to the dangers inherent in a law enforcement agency whose mandate is one of “homeland security,” a quest without bounds, while highlighting the need for extraordinary vigilance by civil and human rights advocates.

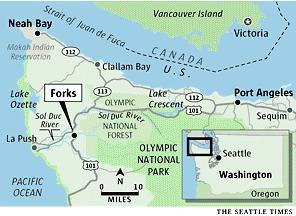

In the last several years, the Border Patrol has experienced dramatic growth in northern Washington, a place where the agency’s presence was symbolic not too long ago. According to a recent article in the New York Times, the number of agents in the small area of the Olympic Peninsula alone, for instance, has increased tenfold over the last six years, from 4 in 2006 to 40 or so today. There, in Port Angeles, a city of 19,000 or so, the agency has just completed the building of a new station—at a cost of approximately $10 million—one with a 40-foot radio tower, two holding cells, a kennel, three dog runs, and a fitness center. It can house up to 50 agents.

There, in Port Angeles, a city of 19,000 or so, the agency has just completed the building of a new station—at a cost of approximately $10 million—one with a 40-foot radio tower, two holding cells, a kennel, three dog runs, and a fitness center. It can house up to 50 agents.

As is typically the case, Border Patrol spokespeople point to the threat of terrorism and cross-boundary crime (emanating from Canada in this case) to justify the agency’s growing presence and power. But as whistleblowing agent Christian Sanchez revealed last year in relation to what actually goes on in the Olympic Peninsula, the agency has “no purpose, no mission.”

Testifying to the Congressional Transparency Caucus of his own experience, Sanchez stated that “there was rarely any casework to be done, if at all, so I just roved from X to X, wasting gasoline.” According to the sheriff in the county in which Port Angeles is located, Border Patrol agents in the area simply don’t have much to do. Speaking in 2011, he said: “I know (the Port Angeles section's) activity. I think they made less than 20 arrests last year.” In the view of Sanchez, who experienced retaliation from his supervisors for his outspokenness, the growth in resources that the agency has seen “is to expand bureaucratic turf.”

According to the sheriff in the county in which Port Angeles is located, Border Patrol agents in the area simply don’t have much to do. Speaking in 2011, he said: “I know (the Port Angeles section's) activity. I think they made less than 20 arrests last year.” In the view of Sanchez, who experienced retaliation from his supervisors for his outspokenness, the growth in resources that the agency has seen “is to expand bureaucratic turf.”

With little to do in terms of the national and community threats invoked by the Border Patrol, its agents end up focusing their attention on everyday residents and workers, often seeking human prey on roads and lurking around grocery store parking lots, gas stations, local schools, and the like in the never-ending search for “illegals.” As one local denizen critical of the agency asked, “What’s the purpose of the Border Patrol in a place that has no border problems?”

With its “bureaucratic turf” enlarging throughout Washington, this is a question that is not limited to the Olympic Peninsula. Skagit, Whatcom, and Snohomish counties (to the east of the Peninsula), for example, have also seen marked growth in the number of Border Patrol agents.

The result there, says a report issued in mid-April by the immigrant advocacy group OneAmerica and the University of Washington’s Center for Human Rights, is a marked increase in surveillance and harassment of local residents as they go about their everyday activities.

The elevated policing is compounded in municipalities such as Blaine, Lynden, and Sumas, where the Border Patrol plays what the report characterizes as “a particularly unusual role:” the dispatcher for 911 calls. “Upon receiving a call, Border Patrol agents “dispatch civilian law enforcement or emergency services, and if requested, accompany as backup or to provide interpretation. Some interviewees reported that when they called 911, Border Patrol agents arrived alongside first responders, and asked about their immigration status.”

According to the report, three patterns of abuse have emerged in the three county area. They are comprised of “systematic” ethno-racial and religious profiling by Border Patrol agents; “dangerous fusion” in terms of collaboration between the Border Patrol and local and other law enforcement agencies; and deep and widespread fear and mistrust among community members and hence (among other problems) an unwillingness to call upon emergency-service-providers when needed.

In response, the ACLU and the Northwest Immigrant Rights Project filed a class-action lawsuit in late April challenging the Border Patrol’s use of traffic stops and interrogation of vehicle occupants without any legal basis. On a more popular level, groups like the Olympic Peninsula’s “Stop the Checkpoints” contest the Border Patrol’s practices, while the loved ones of unauthorized residents and workers in the region organize communication “trees” to warn when agents are seen in particular locations.

Local and other law enforcement bodies sometimes call the Border Patrol when they encounter individuals who don’t speak English for help with translation. Agents often exploit these requests to inquire about the immigration status of the individuals involved. Moreover, the Bord er Patrol sometimes doesn’t even wait for a request for backup or translation assistance. In Spokane in the eastern part of the state, agents have shown up uninvited in response to municipal law enforcement calls—much to the surprise of some within the Spokane Police Department and the city’s government.

er Patrol sometimes doesn’t even wait for a request for backup or translation assistance. In Spokane in the eastern part of the state, agents have shown up uninvited in response to municipal law enforcement calls—much to the surprise of some within the Spokane Police Department and the city’s government.

In May 2011, Benjamin Roldan Salinas died when he drowned in the Sol Duc River as he fled Border Patrol agents who were trying to arrest him while he harvested salal (an ornamental shrub) in Olympic National Forest. While an extreme example, the tragic case illustrates how heightened immigration and boundary can only lead to greater levels of repression, violence, and suffering. What is taking place in Washington State has profound implications for the ability of families to maintain their unity and the wellbeing of communities in the U.S.-Canada borderlands (see the video below), as well as for human and civil rights more broadly.

For more from the Border Wars blog, visit nacla.org/blog/border-wars. And now you can follow it on twitter@NACLABorderWars. See also "Undocumented, Not Illegal: Beyond the Rhetoric of Immigration Coverage," by Angelica Rubio in the November/December 2011 NACLA Report; "The Border: Funneling Migrants to Their Doom," by Óscar Martínez, in the September/October 2011 NACLA Report; and the May/June 2007 NACLA Report, Of Migrants & Minutemen.