Report

Next year Fidel Castro will confront his tenth U.S. president, with the antagonism between the United States and Cuba little changed from when the conflict commenced four decades ago. The embargo on trade, initially imposed in stages from 1960 to 1963, remains in place.

When the U.S. government first announced its 1989 "Andean Initiative"—a five-year, $2.2 billion plan targeting coca and cocaine production—the Andes region was largely viewed as emerging from the "lost" economic decade of the 1980s and moving towards democracy. Except in the eyes of drug policymakers, the area was low on the list of U.S. concerns.

The new U.S. doctrine also poses dangers to civil liberties in the United States itself. The Clinton Administration doubled federal spending on counterterrorism between 1996 and 2000, and presided over a massive build-up of national counterterror bureaucracies linking the military, law enforcement and intelligence agencies.

Observers of the August 2000 Republican and Democratic Party conventions who hoped to glean some insight into current U.S. thinking on military policy were sorely disappointed. Neither of the two major presidential candidates devoted more than a few minutes to military affairs in their nomination speeches, and much of what they did say was of the generic, "I will keep American forces strong" variety.

“I don’t see why we need to stand by and watch a country go Communist because of the irresponsibility of its own people,” declared National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger in June, 1970, referring to the democratic election that year of Salvador Allende as president of Chile.[1]

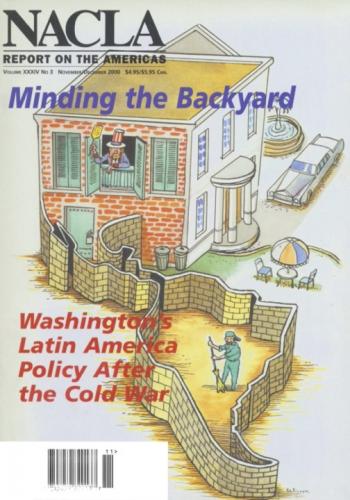

Has U.S. foreign policy dramatically changed with the end of the Cold War? Clearly, the collapse of the Soviet bloc transformed the international system. There is no longer a rival superpower that challenges the United States ideologically, militarily and economically. U.S. security doctrine today is primarily designed to secure and advance the global economic and political predominance of the United States, the main beneficiary of the "new world order" of corporate-driven globalization.

The United States may share a hemisphere with Latin America, but the region is far from the first thing on U.S. policymakers’ minds. In recent years, Washington’s policy towards the region has been reactive—ad hoc responses to what are perceived as problems, like financial panics, immigration, drugs and the Elián melodrama, rather than emerging from any strategic or neighborly vision. Nor has Latin America been much of a concern of electoral politics.

In September of this year, over 2,000 protesters gathered outside the White House demanding an end to the U.S. Navy presence in Vieques, a small island six miles off Puerto Rico that has been used by the U.S. Navy's Atlantic Fleet as a training ground and bombing range for almost 60 years.

Linda Panetta and Randy Serraglio

On November 18 and 19, well over 10,000 people will gather just outside the main gate of the Ft. Benning military base to voice their opposition to the U.S. Army School of the Americas (SOA). Following impassioned testimonies of survivors of violence in Latin America, thousands plan to defy federal law and the warnings of Ft.

Early morning on September 15, El Salvador's Independence Day, the community of Suchitoto was awakened by the roar of planes flying low and fast. "The people knew immediately they were the types flown during the war," observed Sister Peggy O'Neill, a Sister of Charity who has done social work in El Salvador for many years.