While the specific causes, impacts, and responses to protests and violent repression in Nicaragua have been disputed, observers both skeptical and sympathetic to the Sandinista government of President Daniel Ortega seem to agree that the immediate cause of the protests was the government’s mishandling of a wildfire. The fire broke out in the Indio-Maíz Biological Reserve—located in Indigenous Rama-Kriol Territory—in early April. But divergent narratives of the uprising have recast the facts of the Indio-Maíz fire. For some, the government’s response to the fire was slow, insufficient, and hampered by a jingoistic refusal to accept Costa Rican aid, thus reflecting broader failings in an administration perceived to be corrupt, incompetent, and indifferent to a national deforestation crisis. Meanwhile, government sympathizers have argued that the Ortega administration did all it could to prevent and respond to the fire and that U.S.-funded, right-wing civil society groups inspired the protests in response to it.

The dispute over the facts of the fire obscures a long history of government inaction in Indio-Maíz that made the fire virtually inevitable, so much so that back in 2016, one conservation biologist predicted the fire down to its precise cause—a fire set by a settler illegally cultivating rice in palm swamps. It is crucial to correct the record about what happened. The situation also underscores the hypocrisy of Nicaragua’s reputation of environmental stewardship and promotion of Indigenous and Afro-descendant rights, which has earned it leadership positions in international organizations like the UN’s Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues and Green Climate Fund. The causes of the Indio-Maíz fire point to a reality in which the Sandinista government permitted, or even promoted, the destruction of Indio-Maíz and the dispossession of the Rama-Kriol communities in the interest of cattle ranching, agribusiness, and national development plans.

Chronicle of a Wildfire Foretold

The Indio-Maíz Biological Reserve is one of the two best-preserved lowland rainforests in Nicaragua. In addition to serving as a carbon sink, it is critical for the survival of globally-endangered species like the great green macaw and the Baird’s tapir. Ortega established the Great Indio-Maíz Biological Reserve by presidential decree in one of the final acts of his first administration in 1990. The reserve has since become part of the National Protected Areas System under the stewardship of the Ministry for the Environment and Natural Resources. The Rama-Kriol Territory, which overlaps with 80 percent of the Indio-Maíz reserve, consists of approximately 400,000 hectares of land that Ortega titled to nine Indigenous Rama and Afro-descendant Kriol communities in 2009 after his return to office.

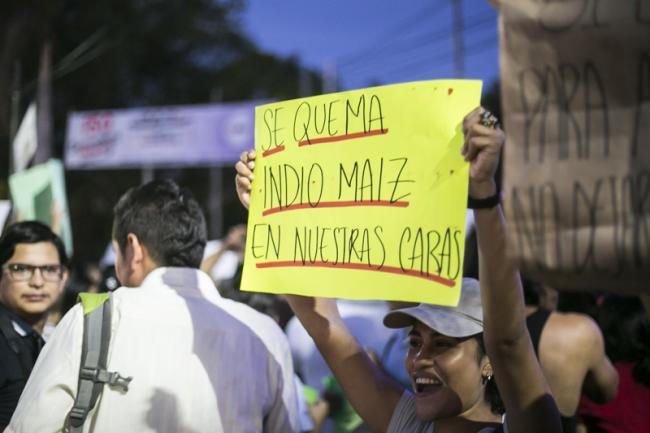

The Indio-Maíz fire broke out on April 3 and burned over 5,400 hectares of land before rains put it out 10 days later. During that time, a protest movement known in Nicaragua as #SOSIndioMaiz took to the streets—in Managua and across the country—to protest the Ortega government’s failure to prevent the fire and slow response to it. Young people—largely students—led the protests and made repeatedly clear, as one group chanted at a protest, “No political party brought us here; indignation brought us here.” Soldiers detained independent media and NGO workers to prevent them from visiting the town closest to the reserve, and Ortega’s supporters were deployed alongside riot police to block and break up the peaceful marches.

Indio-Maíz had become more susceptible to fire when Hurricane Otto hit in November 2016. The storm broke records as the southernmost landfall of any hurricane in Central America and the latest ever Atlantic hurricane to exceed Category 1. Sixteen months before the fire started, conservation biologist Chris Jordan of Global Wildlife Conservation wrote that Hurricane Otto, like hurricanes in the area before it, generated an enormous fire risk in the Raphia palm swamps within Indio-Maíz. Mestizo settlers occupy the Raphia swamps and use fires to clear lands for rice cultivation, even though it is illegal for them to build homes or carry out agricultural activities in Indio-Maíz and the Rama-Kriol Territory. A fire amid the fallen palm fronds can ignite easily and spread across the Raphia swamps, though it would be very unlikely to spread into the much larger broadleaf forests within Indio-Maíz.

Indeed, a settler using fire to prepare a small plot for rice cultivation in the Raphia swamps confessed to having sparked the Indio-Maíz fire. The penalty for igniting a forest fire under Nicaraguan law is two to four years in prison, yet residents of the town of San Juan de Nicaragua near the site of the fire confirmed to me in August that the settler who started the fire had been set free in the town under unclear circumstances.The destruction of Hurricane Otto that provided fuel for the fire was unavoidable, if possibly worsened by climate change, but what was a mestizo settler doing growing rice in the middle of a Raphia swamp in a protected area and an Indigenous and Afro-descendant territory in the first place? This seemed to catch government allies off guard—one argued in Telesur that it was impossible that a settler would have started the fire because the land there was not suitable for agriculture. The settler’s presence speaks to a much larger problem than the fire itself: rampant colonization of a protected Indigenous area, which Ortega’s government has ignored or even promoted.

Communal Lands and (Un)Protected Areas

White and mestizo settlers have colonized Indigenous and Afro-descendant lands on the Caribbean coast of Nicaragua since the 19th century—a history that is central to the dynamics that caused the Indio-Maíz fire and shaped the current uprising. Settler colonialism in the Caribbean coast, including Indio-Maíz, began with the military annexation of the region to Nicaragua in 1894. For several decades after this annexation, Nicaraguan administrations granted private land titles to family members and government officials to settle land where the Rama-Kriol people live along rivers. The Somoza dictatorship (1936-1979) continued and expanded this practice through a colonization project that created incentives for mestizo peasants to settle further and further east. That project particularly focused on settlement in Nueva Guinea, an area that would decades later become a critical hub for settlers who deforest both Indio-Maíz and the Rama-Kriol Territory. In the Somoza years, the growing cotton industry, largely owned by the Somozas and their allies, as well as natural disasters, displaced smallholding mestizo peasants in the Pacific and Central zones of the country. The Somoza regime and the Inter-American Development Bank, which funded the project, saw the Caribbean coast’s Indigenous and Afro-descendant lands as an open space for the peasants’ resettlement.

Colonization as well as the cotton industry contributed to massive deforestation in the region. While this deforestation slowed in the 1980s as residents fled the violence of the Contra war, in the 1990s the neoliberal government of President Violeta Barrios de Chamorro (1990-1997) began to resettle war refugees and ex-combatants on the Caribbean coast. While the Chamorro government ostensibly protected Indio-Maíz under its National Protected Areas System, it simultaneously facilitated the settling of colonists in the areas immediately surrounding it.

Since then, dramatic deforestation and water depletion in the Pacific and central highland regions of Nicaragua—largely attributable to cattle ranching activities promoted by several recent governments—have contributed to an increase in major droughts. With less fertile land available, more settlers have sought to cull the soils of the protected Caribbean coast. In the decades since Chamorro’s presidency, the population of settlers in the area surrounding Indio-Maíz has exploded: the population of the Río San Juan Department, which contains most of Indio-Maíz, increased 79 percent, while the national population increased 42 percent between 1995 and 2014. Indigenous Rama and Afro-descendant Kriol people in the communities of Indian River and Greytown have described to me a three-fold increase in the settler population in San Juan de Nicaragua—just south of Indio-Maíz and within the Rama-Kriol Territory—during approximately the same time period.

Contradiction and Control

Since returning to power in 2007, Ortega has fulfilled his promise to title Indigenous and Afro-descendant communal lands, ultimately titling 31 percent of Nicaragua’s national territory, but in practice his administration has failed to protect these groups from the effects of spreading colonization. The Inter-American Court of Human Rights had already determined the traditional lands of Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples to be inalienable communal property in 2001, but the lands were not titled until 2007. Nicaragua’s communal land law stated that nearly all settlers who arrived in communal lands after 1987 had to come to agreements with the title-holding community or face removal by the state. Yet the Ortega government largely failed to enforce the law or confront the colonization of the Rama-Kriol Territory and Indio-Maíz, reflecting ideological inconsistencies and authoritarian tendencies both in its handling of Indigenous and Afro-descendant issues and more generally. The communal land titles and protected areas have become empty promises as the pace of colonization has continued or even increased from the years of neoliberal governments (1990–2007).

The Ortega administration represents a spectrum of approaches to Indigenous and Afro-descendant issues, from outright racism and dismissal on one extreme to cooptation on the other. For example, Manuel Coronel Kautz, a senior government official who served as the chairman of the ill-fated Nicaraguan Grand Interoceanic Canal Authority, has spoken on camera about Rama people as being too small a group to matter and as racially incapable of doing “serious” business. Coronel Kautz, a loyal Ortega supporter, faced no consequences for his remarks. Meanwhile, senior Sandinista officials in the Southern Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region often express their support for Indigenous and Afro-descendant self-determination publicly, but in practice insist on obedience from Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities in exchange for any government support. It is often impossible to know what is guiding government policymaking—whether overt racism, the desire for control over communities, or some other approach—but the end result has been unmitigated colonization.

Several recent episodes highlight this dynamic, which hides behind seemingly lawful procedures. In the regional capital of Bluefields, the Afro-descendant communal government filed a massive land claim in 2006 that included the city of Bluefields itself and virtually all otherwise unclaimed portions of the Caribbean coast region to its south. Sandinista officials asked the communal government to reduce the scope of their claim. They refused, leading Sandinista officials to exploit an unrelated internal dispute to create a parallel government in the area, through which, the regional party secretary directed to submit a claim to only seven percent of the original land claim, according to emails that communal members showed me.

The parallel communal government received a title to the much smaller claim and, according to my conversations with Sandinista officials, is now allowing mestizo Sandinista settlers to enter the lands in exchange for agreeing to labor on plantations owned by a Kriol ally of the Sandinista government. Meanwhile, the original communal government continues to struggle to have its full land claim titled.

Similarly, the proposed Grand Interoceanic Canal project, which would have bisected both the Rama-Kriol Territory and the original Bluefields land claim, involved a farcical consultation process with the Rama-Kriol Territorial Government. After the announcement of the project in 2012, Rama-Kriol leaders pressured the Sandinista government to comply with Nicaraguan laws and international norms requiring that the state consult with affected communities. According to my interviews with territorial leaders, video recordings, and media accounts, Sandinista central and regional government officials responded by paying a group of territorial leaders the equivalent of two months’ salary to join them in one 24-48 hour visit to each Rama-Kriol community where they presented only the potential benefits of the project. This was termed in official documents a “pre-consultation.”

Yet without further visits, the central and regional governments flew a minority of territorial government members to Managua for a ceremony in which the territorial president signed a “Free, Prior, and Informed Consent Agreement” for the canal—despite the fact that the territorial government had approved a resolution two weeks beforehand instructing him to do no such thing. The chain of events began with the government’s refusal to comply with Indigenous and Afro-descendant rights laws and continued with bribery, coercion, exclusion of critics, and, ultimately, a performance of government compliance with international standards.

In Indio-Maíz itself, the government has failed to respond to Rama-Kriol forest rangers’ thorough documentation of illegal colonization. Perhaps the most egregious is the case of cattle rancher José Solís Durón. In early 2017, forest rangers discovered his 5.4-square-mile ranch inside Rama-Kriol Territory and Indio-Maíz. Solís Durón has admitted to purchasing and deforesting the lands, which violates a slew of Nicaraguan laws. After the Rama-Kriol Territorial Government and ranching industry groups pressured the Nicaraguan government to act against Solís Durón, government forces—without notifying the Rama-Kriol communities—entered the territory and burned down the ranch. But when a government prosecutor then followed up by ordering an investigation and opening criminal proceedings in October 2017, he was promptly fired. No further actions have been taken despite requests from the Rama-Kriol communities for the investigation to proceed, and drone footage from forest ranger patrols shows that Solís Durón’s workers have begun rebuilding the ranch.

Most directly related to the fire, MARENA, the Ministry for the Environment and Natural Resources, and other government bodies have consistently failed to comply with the terms of a Joint Management Agreement for Indio-Maíz they signed in 2011 along with the Rama-Kriol Territorial Government and the regional government. In the original agreement, MARENA and the regional government pledged to strictly enforce laws that prevent the entry of settlers and follow up on complaints against settlement activities, none of which has happened. Further, in a 2017 agreement, the minister of MARENA agreed to involve municipalities in the Joint Management Agreement. Such action could have prevented the settlement activities that sparked the fire.

Instead, the Sandinista mayor of the municipality that included most of the area affected by the fire, San Juan de Nicaragua, has publicly denied that the Rama-Kriol Territory has any land rights within the municipality, claiming their title is either purely symbolic or an error in the land registry. The municipality has seized revenues that rightfully belong to the Rama-Kriol communities, and Rama-Kriol leaders have told me that the state has provided educational and health care services to recent settlers in Rama-Kriol lands within Indio-Maíz that are denied to Rama-Kriol community members in the same area.

The Ortega administration’s actions and inaction have allowed dispossession and deforestation to continue virtually unmitigated, even while legally recognizing Indigenous and Afro-descendant communal lands. The presence of the settler in the Raphia swamps who ignited the Indio-Maíz fire was no aberration; rather, his presence was virtually inevitable due to the Ortega government’s approach to communal lands and protected areas.

Nicaragua’s Climate Hypocrisy

Going forward from the Indio-Maíz fire, the Ortega government’s authoritarianism and pacts with the right all but guarantee that the actions that made the fire inevitable will continue or even worsen. Ironically, this has become clear as Ortega government representatives have continued to defend Nicaragua as a uniquely environmentally-friendly country, even in the aftermath of the fire.

Recall that Nicaragua famously rejected the 2015 Paris Agreement on the grounds that it did not go far enough to reduce emissions and failed to account for global inequalities in terms of both the ability to reduce emissions and the historical responsibility for emissions. Indeed, Nicaragua, which is particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change, has dramatically increased renewable energy sources in its electrical grid under Ortega’s administration—to nearly 50 percent. When Nicaragua finally changed course and signed on to the Paris Agreement in 2017, Paul Oquist, Nicaragua’s lead climate negotiator, seemingly leveraged the move to gain the co-chairmanship of the UN’s Green Climate Fund.

With the Indio-Maíz fire and the outbreak of violence earlier this year, this track record is now being called into question. Since the fire, however, Oquist has made explicit a government strategy that refuses to contend with the causes of the fire and the ongoing crisis of colonization. Oquist claimed in Telesur that the government’s “peer pressure” approach has been “highly significant in reducing slash-and-burn agriculture.” What this means in practice remains undefined, and conservation experts and residents in the area are confused and concerned about these claims. Further, Oquist announced that the government plans to give settlers “farms that have valuable trees, robusta coffee, and cacao: valuable assets they won’t abandon.” Amid the current, virtually non-existent levels of protections for biological reserves and communal lands and communal lands, though, this strategy would reward colonization and do nothing in itself to prevent the same settlers from taking additional lands. When asked about this strategy, one senior Sandinista official in the region told me, “I hope that’s not the plan,” and insisted that she knew nothing about it.

Finally, Oquist has touted the Ortega government’s steps to implement ENDE-REDD+, the Nicaraguan Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries (REDD+) program. Yet Ortega’s alliance with the private sector at the expense of Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples has made residents wary. In the first place, the only consultation for ENDE-REDD+ has been a one-day meeting with the Ortega-recognized presidents of Indigenous and Afro-descendant territories, which includes the leaders of parallel governments rather than the leaders recognized by the peoples themselves. Per Nicaraguan law and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, the consultation should take place through each affected community, not just by the presidents. Worse yet, the proposed $80 million budget for ENDE-REDD+ includes only around $13 million in direct incentives to Indigenous and Afro-descendant territories to reduce deforestation, while giving nearly $41 million in credit lines and guarantees for agroforestry trusts—that is, the agriculture and ranching industries.

These actions in the aftermath of the Indio-Maíz fire point to a few trends in the Ortega government’s policies that make future catastrophes highly likely. Indeed, Rama and Kriol community members report that the pace of colonization in Indio-Maíz has only accelerated since April. To prevent further environmental catastrophes in communal lands, which include most of Nicaragua’s remaining forested lands, the Nicaraguan government must fulfill its obligations to Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples to prevent further colonization. Oquist’s defense of current and planned Ortega government policies gives no reason to hope for such changes.

Yet, interestingly, it is the ruling party itself that has in fact fostered protestors’ passion for environmental issues prior to the #SOSIndioMaiz protests, and their protest strategies come from the same vocabulary of resistance that the Sandinistas employed during the revolution and the years of Sandinista opposition to neoliberal governments. This may be a cause for hope amid the current crisis. The fact that young protestors chose to stand up for their values over their party during and since the Indio-Maíz fire shows that, amid the ideological diversity and contradictions of the opposition, the people willing to risk their lives for a better Nicaragua are unlikely to cave to the interests of big agriculture and big business more generally within the national opposition. The emergent alliance of Indigenous and Afro-descendant folks and leftist students could be the country’s best hope for halting deforestation, reversing colonization, and avoiding the otherwise inevitable sequels to the Indio-Maíz fire.

Josh Mayer is a doctoral student in sociocultural anthropology at the University of California, Los Angeles. Since 2014, he has carried out more than a year of ethnographic research on territoriality, governance, sovereignty, and race in the Indigenous and Afro-descendant Rama-Kriol Territory in southeastern Nicaragua. Mayer was raised in Portage, Michigan, on the ancestral lands of the Bodéwadmi people.