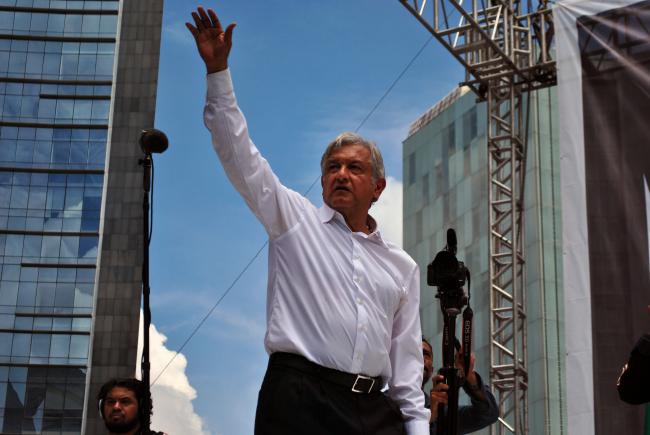

When Andrés Manuel López Obrador was elected president of Mexico last year, many hoped that his presidency would bring a hard shift away from the militarized approach to combating organized crime pursued by previous administrations. Seven weeks into López Obrador’s term, the biggest shift so far has been to emphasize oil theft, or huachicoleo, over narco-trafficking as public enemy number one. After a catastrophic explosion at an illegally tapped oil duct in mid-January, however, this emphasis on huachicoleo might set the president on the path of re-militarization.

One of the central pillars of López Obrador’s election campaign was the need for a more humane security policy. He laced his campaign with slogans such as “abrazos no balazos” (hugs not gunfire, or, hugs not slugs), tapping into broad dissatisfaction with persistently high levels of insecurity in the country. The previous two administrations sustained the so-called war on narco-trafficking, but both administrations left the country with higher levels of violence than they found it. During his campaign, López Obrador floated ideas such as amnesty for low-level recruits in criminal organizations. Since his inauguration, he has maintained the same rhetoric—declaring an end to the war on drugs in late January—while continuing to militarize security through the creation of a National Guard.

Early Moves Against Huachicoleo

López Obrador’s early attention to crime has focused mainly on oil theft. When López Obrador talks about oil, he articulates it as a question of sovereignty. He talks about rescuing the state-owned oil company, Pemex, describing this as vital for the country’s future. He also invokes the legacy of Lázaro Cárdenas, who nationalized Mexico’s oil and founded Pemex in 1938. With oil elevated to the level of national patrimony, its theft becomes a cardinal sin against the nation itself.

Locally known as huachicoleo, oil theft is nothing new in a country crisscrossed by oil ducts. Huachicoleo did, however, increase sharply during the Peña Nieto administration (2013-2018). The majority of oil theft occurs within Pemex infrastructure such as refineries and offshore drilling platforms, and thus directly involves the participation of Pemex officials. The term huachicoleo is, however, more often associated with illegal perforation and tapping of the ducts that transport refined gas throughout the country; this type of theft involves groups of huachicoleros that sell their stolen product to local markets. During 2012, Pemex recorded 1,635 illegal perforations of oil ducts. By 2018, the number had risen to 12,581 illegal perforations. Pemex recorded these perforations, but took little action to prevent them. Indeed, a seemingly corrupt and moribund Pemex suited Peña Nieto’s agenda of privatizing oil production, even as his policy of ending gas subsidies created a domestic demand for the cheaper gas provided by huachicoleros.

Within a month of his inauguration, López Obrador’s government put the Plan Conjunto de Atención a Instalaciones Estratégicas de Pemex (Joint Plan for Attention to Strategic Pemex Installations) into action, which saw security forces take over monitoring parts of Pemex’s oil distribution network, in order to decrease theft by disrupting complicity from within Pemex. The plan was enacted very quickly during the busiest time of year for fuel consumption, and led to shortages at some gas stations, and long lines at others. While some were enraged and viewed the long lines as proof of the Venezuelization of Mexico, López Obrador’s approval ratings steadily increased throughout this period.

As part of the Joint Plan, López Obrador also advocated reforms to mandate harsher punishments for oil theft. In total, the Senate proposed nine crimes that would result in automatic preventive prison—upon review by the Chamber of Deputies, the list of crimes was reduced to three. Oil theft is one of the crimes still under consideration for such punishment, while the crimes removed from consideration include sexual violence against minors, feminicide, and forced disappearance. Automatic preventive prison is hardly a more humane approach to security, and the government is seemingly wary of using it too broadly. That huachicoleo has been prioritized as a crime in need of such a strong deterrent indicates that the government sees the issue as an urgent one.

Public Enemy Number One

The administrations of Felipe Calderón (2007-2012) and Enrique Peña Nieto initiated and continued the country’s war on narco-trafficking with the support of the United States, but each administration focused specifically on different groups as the most urgent security threats. The Calderón administration went after the Zetas, weakening the group in the later years of Calderón’s presidency. This focus led some to argue that Calderón targeted the Zetas because of a special relationship with the Sinaloa Cartel, an accusation that re-emerged during the Chapo Gúzman trial in New York. The Peña Nieto administration, by contrast, made a point of targeting the Sinaloa Cartel (arresting Gúzman not once but twice), but left the Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación (Jalisco New Generation, CJNG) to expand and fill the void created by Gúzman’s fall.

Some security analysts accordingly saw CJNG as the biggest security challenge facing López Obrador. Instead, he has changed the conversation, shifting emphasis from specific groups of narcos, to the phenomenon of huachicoleo and its ties to corruption within Pemex. This could be an astute move, given how little success his predecessors had with winning the war on narco-trafficking. Furthermore, any advances against huachicoleocould see more oil revenue flowing through state coffers, giving López Obrador more resources to devote to social programs.

López Obrador has not declared war on oil theft in the same manner as Calderón publicly announced his war on narco-trafficking in 2006. He rarely uses the term huachicolero; instead, he tries to keep the focus on Pemex. However, once he set the national agenda by identifying oil theft as a national security threat, many in the media interpreted this as a declaration of war against huachicoleo. Even newspapers like Jornada and Proceso, which were critical of militarized security policy under the previous administrations, have repeatedly run headers about a war on oil theft, sustaining a discourse that articulates security in terms of militarization.

The huachicolero was already a well-established trope in the media. The stereotyped huachicolero wears a baseball cap and a bandana covering his nose and mouth; he goes about in jeans or overalls (often stained with grease), and carries a jerry can or possibly a gun, combining attributes both of the mechanic and the bandit. This trope became a convenient image for a new public enemy number one.

As Oswaldo Zavala documents, the image of the quintessential narco—an uncouth but sharp guy from the north in pointed boots and cowboy hat—was a similarly convenient image (albeit one divorced from reality) during Calderón’s presidency. Where the caricatured narco is from northern, rural Mexico, the caricature of the huachicolero depicts him as from the poor, urban peripheries. Indeed, huachicoleo is a regional phenomenon centered on states clustered around Mexico City. Despite these differences, both the narco and huachicolero caricatures represent men from marginalized areas as dangerous criminals.

Tragedy in Tlahuelilpan

On the evening of Friday, January 18, hundreds of people gathered at a perforated oil duct in the municipality of Tlahuelilpan, in Hidalgo state. An illegal tap of an oil duct was hardly a new occurrence in the municipality—23 such perforations were recorded in 2018—but this perforation turned into a geyser, sending high octane gas gushing meters into the air. Soldiers deployed to the site, but they would or could not disperse the growing crowd. While the oil fumes drove some people back, others approached to collect free fuel. Amidst the throng of bodies drenched in gas, the fumes ignited; the resulting conflagration burned for hours. 130 people died during or after the explosion, with many more injured.

The tragedy at Tlahuelilpan raised the stakes of the discourse about oil theft as a national security threat. On one hand, this confirms López Obrador’s agenda. If the president’s handling of the shutdown of parts of the oil distribution network had at first seemed hasty, after the explosion his early moves against huachicoleo looked prescient. On the other hand, the simplest explanation for the explosion is that it was caused by huachicoleros, which drags attention away from López Obrador’s emphasis on Pemex and corruption, and onto local criminal bands. If the huachicolero was already seen as a threat to national security, after the explosion he becomes a direct threat to the safety of innocent people.

After the explosion, López Obrador doubled down on his plans to combat oil theft. Within a week, he announced his Desarrollo para el Bienestar (Development for Wellbeing) plan, which would bring social programs to 91 municipalities crossed by oil ducts. 23 of these municipalities are in Hidalgo state. He continued to emphasize that the roots of huachicoleo lie in poverty. With social programs on the way, he called on people to cut any ties with huachicoleo and denounce those that would not.

López Obrador’s position shows some intent to maintain a more humane security policy, but it also opens up the possibility of greater militarization of the government’s efforts to reduce oil theft. The soldiers at Tlahuelilpan could probably have dispersed the gathering crowd through a more forceful intervention, but that could have led to other kinds of abuses. With the huachicolero elevated to public enemy number one, there will be pressure to use the military more aggressively against this supposed threat.

Days after the tragedy, a huachicolero boss was killed in a municipality adjacent to Tlahuelilpan. This may have been rough community justice, score settling by soldiers in the area, or a turf struggle among gangs. Whatever the motive, the violence is an ominous sign that “abrazos no balazos” is likely off the table as a security policy.

The Road Ahead

At the two-month mark of his presidency, López Obrador finds himself with a strong mandate to tackle huachicoleo. He has shifted security discourse away from narcos and onto oil theft. In doing so, however, his government prioritizes re-militarization over demilitarization and a more humane approach to security. This plays into López Obrador’s plans for the National Guard, but not quite into his plans for Pemex. After the tragedy at Tlahuelilpan, public enemy number one is less likely to be the corrupt Pemex official that sells off the national patrimony, and more likely to be the huachicolero that perforates oil ducts and risks causing another devastating loss of life.

Greater focus on huachicoleros will likely bring a stronger military presence to oil infrastructure and huachicoleo hotspots. For states such as Hidalgo and Puebla, which have avoided the worst excesses of the war on narco-trafficking, this should be a serious concern. While there have been reports of huachicoleros leaving the region around Tlahuelilpan for fear of locals turning on them, some bands dedicated to oil theft are likely to resist any move to diminish their power and revenue. Even if militarization can at times disrupt crime, the past 12 years strongly suggest that it also exacerbates violence.

Furthermore, the public enemies of previous administrations will not disappear simply because they are starved of headlines and public attention. Will narco groups adapt to this opportunity to retreat from the spotlight, or will they double down on the use of spectacular acts to compete for public notoriety? Regardless of who is declared public enemy number one, the global economy of illicit drugs and local economies of extortion remain lucrative.

Finally, the similarities between López Obrador’s early mandate and the initial surge of support for Calderón’s war on narco-trafficking may be instructive. Early cross-party support for Calderón evaporated as the human toll of his war increased, with no clear path away from violence in sight. By nominating oil theft as public enemy number one, López Obrador committed himself to acting decisively against this crime. After Tlahuelilpan, he will have to balance short-term calls for militarization with the long-term risks of doing so. He will also have to balance targeting the obvious figure of the huachicolero with less immediate policies to counter corruption in Pemex and address the root causes of crime in marginalized communities.

Philip Luke Johnson is a doctoral candidate in political science at the Graduate Center, City University of New York. His dissertation research focuses on narco-messages and the media in Mexico. Between research trips he teaches at Hunter College.