Off the cliffed coast of La Guajira, Colombia’s northernmost province, two neat lines of 20-story-tall wind turbines tower over a cluster of clay huts and goat herds. Since 2004, the wind energy pilot project known as Jepírachi, created to study the prospect of wind power in the region, has stood as the only wind farm in Colombia.

But with wind proven to be a viable renewable energy option, companies are flocking to the region in a bid to transform La Guajira into the country’s wind power provider. Nineteen national and multinational corporations plan to mount 60 projects in the province, almost all on Indigenous Wayuu land. It’s a move that would ensure clean energy for a rapidly growing population, but it is also prompting age-old questions about the rights of Indigenous peoples.

At first glance, the advent of wind power in Colombia may seem like an uncontroversial policy decision. Wind power is expected to provide up to 20 percent of the population’s electricity needs—an important feat as the weather phenomenon known as El Niño strengthens with climate change and dwindles the capacity of hydroelectric dams, Colombia’s main energy source.

But the development has also provoked discussion about how to safeguard Indigenous rights when they stand in the way of lucrative, albeit green, businesses. The issue has surfaced around the world, particularly in Latin America, as the wind energy industry booms. According to the international Business and Human Rights Resource Centre (BHRRC), more than 50 percent of reported conflicts surrounding renewable energy projects in the past decade have been in Central and South America.

Just as European colonization and a slew of modern development projects have displaced native communities from their fertile lands, BHRRC reports that clean energy companies are stripping Indigenous people of their territories, particularly for hydroelectric development, but also increasingly for wind farms. UN special rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples, Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, has highlighted the imposition of renewable energy projects—including solar, wind, and hydropower—without adequate consultation of local residents. In La Guajira, rights activists warn that Indigenous communities could forfeit control of their lands to wind energy companies—for little compensation—if poor consultation practices persist.

Questionable Consultation

La Guajira is the ancestral home of the Wayuu nation, the largest Indigenous group in Colombia with more than 400,000 people. Here, the Wayuu have lived since before borders existed, resisting colonization and residing between modern-day Colombia and Venezuela for more than a millennium. La Guajira is also a province where companies have extracted coal, natural gas, salt, and other precious materials since the 1980s. Persistent multinational projects have failed to translate into long-term development for this region fraught with poverty and corruption.

Supporters of the wind energy industry argue that Wayuu communities—many living without running water or electricity—will finally see a favorable deal. Still, there’s doubt and a lot at stake: According to a recent study by the Colombian think tank Institute for Development and Peace Studies (Indepaz), 288 Wayuu communities could be affected and 35 percent of ancestral lands could be allocated for wind farms. It’s a “gigantic project,” the report reads, with close to $6 billion in investments.

An Indepaz map shows that proposed wind farms—about 2,000 turbines in total—would dramatically transform the region’s landscape. Most are expected to dot the Venezuela-Colombia border, the northernmost point of the peninsula, and the shores of the popular tourist destination, Cabo de la Vela, in the northeast. But some would even reach farther south, near the foothills of the Sierra Nevada massif.

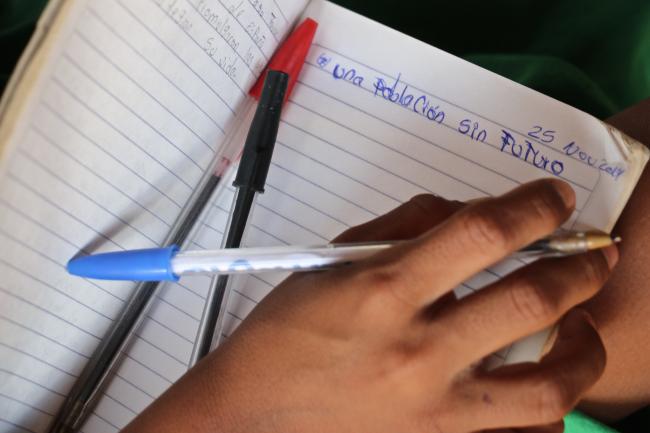

According to the 186-page Indepaz study, one of the few reports that has explored the ramifications of a wind energy “revolution,” neither the communities interviewed nor the population at large reported to understand the scope of the projects nor their potential impacts. Coauthor Joanna Barney attributes this to the failure of the prior consultation processes. According to Colombia’s 1991 Constitution, companies must seek the consent of Indigenous and Afrodescendent communities before intervening on their lands.

But this right has often been trampled in Colombia. In La Guajira, the El Cerrejón open pit coal mine has faced criticism for its failure to adequately consult local communities. While El Cerrejón started operations years before the 1991 Constitution mandated this measure, families who sold their land to the multinational claim any prior information given on the project was misleading. Then, in 2017, Colombia’s top constitutional court ordered the mining company to pause plans to expand the area of coal production due to concerns over consultation rights violations.

A 2015 Oxfam report concluded that despite a growing body of regulations and jurisprudence, Colombia has faced problems in implementing these protections. Human rights organizations such as Nación Wayuu argue that in the case of the wind farms, corporations are engaging with communities superficially, failing to provide the Wayuu with the technical and legal assistance needed to make informed decisions, as prescribed by law.

“These prior consultations with Indigenous communities that are underway are completely illegitimate,” said José Silva, president of Nación Wayuu. “They should include the participation and accompaniment of independent experts in Indigenous relations and human rights, specialized in prior consultation.”

Santiago Villegas, director of planning and energy production at the public utilities company EPM—which plans to build three wind farms in addition to the already operational Jepírachi wind farm—agrees that Indigenous rights groups such as the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia should accompany these dialogues to advocate on the behalf of communities in the design of sustainable development projects and to guarantee a clear and accurate exchange of information.

Still, Silva says that most communities—many of them uneducated about their legal rights—are left alone to negotiate with large national and multinational companies. “What happens to those communities that aren’t accompanied? What kind of deals can they reach?” Silva asked. These questions are at the heart of a brewing conflict surrounding the wind energy boom.

A Matter of Survival

La Guajira, a diverse region of desert flatlands, vast coasts, and tropical forest mountains, is the fourth poorest province in the country. Uribia, a windswept desert plain in La Guajira where many wind farms are projected to take shape, is Colombia’s poorest municipality, with 92.2 percent of its people living in precarious conditions. Many lack access to education, health care, employment, and basic utilities such as electricity and running water. This is attributed to a history of state abandonment, an inaccessible geography, and wide-spread corruption—the inspector general has removed four governors from office since 2000. Meanwhile, climate change-induced droughts increasingly cause crops and livestock to perish, giving way to a lethal malnutrition crisis among lactating mothers and children.

Human rights organizations say these conditions of desperation and extreme state neglect have tipped the power balance toward the green energy companies, which offer payments in the form of development projects instead of cash that communities can use as they see fit. “These communities are dying of hunger and thirst so they ask for things that the state should give them,” said Barney of Indepaz. “They ask for water, education, electricity, and transportation. They’re negotiating with a grocery list.”

In Jasaainmou, a rural hamlet of some 10 families located about three hours away from the nearest town of Uribia, the Italian multinational Enel Green Power has reached a preliminary agreement with local traditional authorities to build a 200-megawatt wind farm capable of powering 60,000 U.S. homes.

Adelco Larrada, one of these leaders, says a corporate representative first arrived in 2014. “At that time, we lived in complete abandonment. I would seek help from the province—and nothing. I spent three years knocking on doors to see if we could get help from family welfare for children who were suffering from malnutrition,” said Larrada, the tall, yet soft-spoken leader.

After a prior consultation period of about four years, 16 communities have consented to the 1,500-hectare wind farm. As compensation, the communities will each receive $19,500 in projects annually for 30 years. Each community will also receive about $306 in projects per month from the time Enel receives its environmental license until construction begins. The company promises to provide running water, electricity, and health centers.

Larrada admits he’s unsure whether the payments agreed upon may be low, as others have suggested to him. He wasn’t informed about the profits the wind farm would make, acknowledging that neither independent lawyers nor experts advised him. He says that he didn’t trust individuals, outside of his community, to be free of the company’s interests.

Yet, he’s optimistic that the extra income promised will benefit his community.

“A politician told me I was being too permissive with the companies,” Larrada says. “I replied that I didn’t think I was being too permissive, rather that given the conditions my communities live in, we see the companies as hope. And I told him that that was their fault—the government’s.”

On a starry November night in Jasaainmou, Larrada says he dreams of pooling his community’s share with that of another three to build a much-needed aqueduct. This community has many urgent needs: Farms have shriveled up from the lack of rain, and families struggle to feed everyone. Work is scarce, especially as family members have returned from Venezuela. The Wayuu people are binational and claim land on both sides of the border.

Addressing the water crisis is Jasaainmou’s top priority. Due to the light rainfalls this year, families must drink murky water from a nearby rain-fed lake that causes stomach problems. Larrada says sometimes it gets worse. During long droughts, when the lake dries up, people wait in long lines before sunrise to retrieve salty water from artisanal wells. “It’s not very fresh, but it’s water,” he said.

Amid an ongoing malnutrition crisis that claimed the lives of 4,770 children in La Guajira between 2008 and 2016, Colombia’s Constitutional Court ruled in 2017 that the state must protect the lives of Wayuu children and lactating mothers by guaranteeing healthcare, potable water, and food security in La Guajira’s northernmost municipalities, where corporations hope to build their wind farms.

More than two years later, change has yet to arrive. Although officials met with Wayuu authorities and local representatives in November 2019 to lay out a plan of action, a few weeks later the Inspector General’s Office and the Ombudsman’s Office declared the government had so far failed to comply with the court decision. They noted that the government had yet to finalize a plan of action as of December 2019.

These conditions are driving communities to support wind energy proposals, say critics. Most already are. Only a handful—about 20—have declined companies’ propositions, said Silva. Indepaz reports that most projects are still in the prior consultation phase, but construction on those that have secured environmental licenses could begin this year. As of February 14, the national government has granted licenses to three wind energy projects. Operations could start as early as 2022 once substations are completed.

According to Silva, the government must level the playing field by protecting the Wayuu people’s basic rights before these projects proceed. Otherwise, communities will fall prey to the pressures of the renewable energy industry. He also argues that these companies’ outsized role in the province could lead to the Wayuu people’s dependence on the private sector, perpetuating state abandonment and keeping communities in a state of submission.

Others insist that most communities won’t wait around any longer to see if the state complies with its obligations. “Either they depend on the private sector or on help from the public, which will never arrive,” said Eliumat Maza, an official at Corpoguajira, a state entity that oversees environmental licensing for smaller projects in the province. “It’s about survival.”

Differing Visions

At a community meeting in Ipapure, a goat-herding hamlet only a stone’s throw away from the border, some 20 elders speaking the traditional Wayuunaiki language discuss EPM’s offer to build a 200-megawatt wind farm of about 67 turbines. Following the Jepírachi pilot project, EPM plans to erect another three wind farms, including one in Ipapure.

Everyone voices different concerns—that there will be less land for their herds to graze or that the arijunas or outsiders will change their way of life—but the consensus is that a wind farm would bring more harm than good. Elders also underline the importance of the land, considered in Wayuu culture the mother of the Indigenous nation. It’s also where they build their homes, where their animals feed, where their ancestors are buried, and where sacred natural forms, such as mountains and rivers, reside.

“We don’t want to lose the only thing we have,” said 69-year-old Brinolfo Epieyuu, the community’s cultural steward.

Ipapure is one of the few Wayuu communities that has stood against the advance of the wind energy industry. In contrast to other communities, the people of Ipapure are better off. Drought is still an issue, but everyone has clean water to bathe, cook, drink, and clean. Cultural preservation is also a key tenet of the boarding school that lies at the center of the community.

Knowledge of EPM’s track record in La Guajira also informed their decision. Ana Iguarán, a teacher and a community leader of Ipapure, said the precedent set by the Jepírachi wind farm discouraged their ancestral authorities from greenlighting any wind energy projects on their land. They visited the 15-turbine wind farm in 2007 to see what future they could expect for themselves. But what the elders saw disappointed them.

“I asked [EPM officials] why the houses next to the wind turbines were so poor,” Iguarán recalled. “I saw my Indigenous sisters cooking a small fish, the only food they had, with firewood on the floor.”

In 2003, the community of Kasiwoluin, one of the two ancestral landowners of the area where the 15 turbines are located, received a one-time sum of roughly $13,500. Along with the community of Aerutkajui, Kasiwoluin also received nine fishing boats and a sea wall. EPM granted compensation in the form of housing, new traditionally-built reservoirs, supplies for the school and health center, a desalination plant and its maintenance, among other benefits.

Still, communities live in poor conditions. Homes have water but no electricity—despite their close distance to a wind farm. EPM, which offers a handful of security guard and janitor positions at its offices, has tried to implement a series of business efforts, such as a fishing cooperative, without success.

Community advocates say that rampant unemployment and the failure of self-sustaining business initiatives has made some 80 families reliant on EPM—a worrying scenario as the company contemplates the possibility of shutting down Jepírachi.

Meanwhile, conflicts over benefits, especially over the few jobs EPM offers,

has opened a rift among communities. A third Wayuu group claimed ownership of the lands in 2016 and argued they deserved a share of the compensation, too. From late 2016 to early 2017, they blocked operations with a general protest, and EPM yielded to their demands without consulting the other two communities first, claimed Nancy Gutierrez, a local leader. Since then, tensions have remained high between communities.

These conflicts could spread throughout La Guajira, according to experts. “If communities on one ranch are doing fine, but next to them are people who’re starving, there are going to be territorial conflicts,” said a provincial official who wished to remain anonymous. Families who live just outside the project’s perimeters and receive nothing are likely to get into confrontations over compensation, he said. Notably, renewable energy companies that invest 50 percent of carbon credits in affected communities are exempt for 15 years from paying revenue taxes that would benefit all communities in the province.

In Ipapure, community members are already concerned about potential divisions due to disputes over who—whether the ancestral or traditional authorities—can negotiate with outside companies. Ancestral leaders, determined by the antiquity of their clan’s cemetery in the area, typically hold these rights. But Iguarán, who sees the ancestral authorities as her elders, said that when the ancestral authorities rejected the company’s offer, EPM turned to the traditional leaders, who approved the construction of a wind measurement tower.

In Jasaainmou, the drought-devastated community where Larrada and other traditional authorities have signed off on a 200-megawatt wind farm, a 120-meter-tall wind measurement tower was knocked over last year during a quarrel among neighbors over economic benefits.

Officials at the mayor’s office of Uribia, the largest municipality in the La Guajira peninsula, say they seek to avoid conflicts like the ones provoked in Jepírachi by sending Indigenous culture experts to ensure deals are made in accordance with Wayuu cultural conventions. But oftentimes, communities don’t want the local government to get involved in negotiations for fear of corruption. Advocates also believe that to get at the root of the conflict, the mayor’s office must provide relief for impoverished communities.

EPM’s Villegas said the company is addressing a growing chorus of concerns. Although EPM has a wind measurement tower set up in Ipapure near the Colombia-Venezuela border, EPM plans to relocate the proposed wind farm to a new area due to local opposition. Villegas also said that, in the event that Jepírachi closes, the company will develop an adequate exit strategy.

Additionally, the company hopes to support development, not assume the role of the state, he says. “We want to accompany the communities in building a health center or a school, but the services of a health center or a school aren’t guaranteed by the construction of a building,” Villegas says. “That is the responsibility of the state, and we will never be able to supplant that role.”

He added that renewable energy companies in La Guajira are working together to consolidate a single development plan that will benefit the entire region, based on its social, economic, and cultural needs. This includes plans to strengthen the capacity of social organizations and institutions, improve the living conditions of the Wayuu people, energize the local economy, and preserve the region’s environmental and sociocultural riches.

Communities directly affected by individual projects will also be involved as business partners in the future and compensated 2 percent of profits, paid in development projects that promote water security, quality health care, and employment. Although the new company policy is an improvement, community advocates argue it’s still below the renewable energy industry standard in Colombia, which experts report provides 4 percent of profits for community participants in thermoelectric projects and 6 percent for partners in hydroelectric dams.

Most economic models used by Latin America’s wind energy industry can be described as a joint venture between companies—the investor—and communities—the property owners. The communities benefit from land-lease or land-use payments and tax revenues.

But Indepaz points out other business models, used in Denmark, Germany, the U.S., and Japan, that could provide better options. In Denmark, most energy is produced by community-owned wind farms. As one organization reported, ordinary Danes are closely involved with development, help fund the installation of turbines, and own a 50 percent stake in revenues. Communities make big economic returns and generate electricity for their towns.

Nación Wayuu’s Silva asked why the same model can’t be replicated in La Guajira. If the Wayuu could provide electricity for themselves, this would dramatically improve living standards and offer people the opportunity to develop businesses. Fishermen would finally be able to freeze their catch to sell later, for example. The management of wind farms would create high-paying jobs and profits would be distributed among communities.

In a millennium, the Wayuu have survived the onslaught of conquistadors and the encroachment of outside corporations. But Silva imagines more than just survival for the Wayuu. With the possibility of collectively owned wind farms, he envisions wide-spread development, educated young professionals, and an undivided people, who fight to protect their traditional customs and land. “Why can’t we dream?” he asked.

Reporting for this story was supported by the Foundation for Sustainability and Innovation.

Christina Noriega is a journalist based in Bogotá, Colombia. Her work covers human rights, gender equality, the environment, culture, and social movements.