It was not a surprise in Miami, where recent immigrants may vociferously oppose immigration, deny racism, find the idea of free healthcare and education distasteful, and admire Trump. But the Florida International University 2020 Cuba poll has made it official. New Americans from Cuba identify with the Republican Party at a higher rate that their predecessors in the 2000s and the 1990s. The expected bluing of the Cuban American electorate as a result of U.S.-born generations being more liberal than their exiled forebears has been, in effect, neutralized by recent immigrant waves. In a swing state’s most populous region, where close to a million Cuban supervoters make up about a third of the total population, this finding has mystified analysts. It begs the questions: Who are these new voters? What sways their vote?

Hialeah is the place to go to find out. Two thirds of its 95.5 percent Hispanic population or a quarter of a million people identify as Cuban, and of those, Republicans are in the majority. Mayor and council members are all both Cuban and Republican, but presidential candidate Hillary Clinton, like Obama before her, only lost in the so-called City of Progress by a split hair. During the last election, a Trump campaign office on main street was easy to miss, with only a small window poster and a tiny staff of elderly English-speaking out-of-towners. Few houses featured electoral signs at the time, and “Cubans4Trump” flash mobs garnered barely a few dedicated families, transfers from the defunct Jeb Bush campaign. Trump won, but without fanfare.

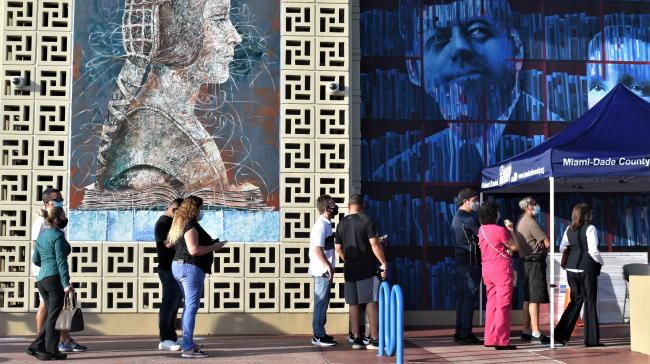

Now, in the fall of 2020, no city block is spared from large Trump banners and tall flags. Voters outfitted with MAGA hats and t-shirts line up for hours outside Hialeah’s central library, the city’s only early voting location. Its parking lot has become a jungle of Trump and various U.S. flags, and Los 3 de La Habana’s viral salsa hit, “I am going to vote for Donald Trump” blasts without pause. On a Tuesday evening, there is no trace of Biden or the Democratic Party among the cheering crowds, and there is no talk of Cuba tomorrow among them, but of America today.

What is the promise of President Trump and Republican policies to the average Hialeah Cuban resident? After ethnographic research, formal interviews, and weeks of canvassing for the local Democratic Party, knocking on thousands of doors and talking to hundreds of residents, I came to the conclusion that not a single issue sealed or broke the deal. Neither the economy, the Second Amendment, immigration, nor U.S. Cuban policy were definitive. The allure was not of policy but of pomp. It was the structure of feeling provided by an effervescent project that would propel a nation into the future. Because what is a nation, after all, other than a project, expressed through symbols?

No president, much less a presidential candidate including Trump four years ago, offered that to them before. The appeal seems to take part in a nation’s pomp, adopt its friends and enemies, and join in as a chosen people with a clean slate. This was also their opportunity to reconstruct a collective mental mapping that would allow them to project themselves forward. No longer exiles, refugees or even immigrants: now they could be Americans first and foremost, all without leaving Hialeah, the most Cuban place outside of Cuba.

Walking Hialeah

In Hialeah the temperature is a few degrees higher than on other greener areas of Miami-Dade County. There are no trees, no shade, and few people out during the day, other than in the corner malls that dot the suburban-looking streets. Front yards are often paved, or have fake grass, more friendly to barbequing than the native South Florida brush. Only the sound of air conditioners betrays human habitation. Inside, the elderly, often visiting from Cuba, take care of babies and toddlers, and children and youth are home now too, attending school online. Then in the late afternoon driveways begin to fill up and neighbors come out. They wash their car, sweep up their front steps, check their mail, or set up a camping table from which to sell plantains, pineapples, and jams. “Things are tough right now,” says one.

The next person on my canvassing list is not home. “That’s my grandmother, she’s in Cuba,” says the youth that opens the door. “She will not be back in time to vote because of the Pandemic,” she explains. A few doors over, the man I ask about moved to Cuba with a new wife and only comes back now and then to cash his social security checks. These are mostly immigrants arrived in the United States after the fall of the Soviet bloc, and many just in the last decade, outnumbering earlier exiles who have moved to more affluent areas of Miami Lakes and Miami Springs. The connection with Cuba is very much alive, and many travel to and from the island regularly.

In multi-generational homes, those under 30 or over 75 are more likely to be Democrats, according to my list of registered voters. At times, I can find the Democrats in rental efficiencies built on the sides or back of the main house. I duck under a huge Trump sign to reach one: “Shhhh, I don’t want them to know that I am for Biden,” the resident tells me. But a significant number of these presumed Democratic voters inform me that they will vote for Trump this time. The reasons are varied but seldom do specific policy issues come up. Occasionally, it is the 401k, or Hialeah becoming great again, before the factories left for China and “you could get a job just like that,” according to a woman who had three jobs in order to make ends meet. “All the countries take advantage of us,” some say. And immigration must be curtailed, just because “no hay cama pa’ tanta gente” (there’s no room for so many people), as many put it.

Many criticize Obama as a weakling who “lowered his pants” before the Cuban leaders and expect no less from a Biden government. Indeed, the FIU Cuba poll has pointed at a reinvigorated support for hardline policies that will choke up the Cuban government. They all cherish their affective ties with relatives and friends in the island and understand that separating the government from the people is just not the way things work. But they are ready to choose the future over the past.

After a while I can tell the Trump supporters’ houses from the Democrats’, not just because of their Blue Lives Matter, QAnon, Trump or plain U.S. flags, but because of their spectacular displays of all kinds. Over the top Halloween decorations, yachts that dwarf the houses, and new European cars. A man with a Goya Foods delivery polo shirt parks his Maserati in front of his modest brick house. He votes for Trump, he says.

One thing is missing from these scenes. The Cuban flag is no longer ubiquitous, as if there were no pride on being Cuban anymore. Cuba is a “shithole” country, tells me one new Cuban-born American. The only possibility for pride is being an American, or better yet, a great American. One man spells it out, “We are here to make America great, this is why we came.”

Trump encourages the kind of bombastic fanaticism usually reserved for sports teams. “He does not need to knock on doors to remind anyone to go to vote,” says a woman without clarifying who is “he.” “He will fix things,” says another traveling avocado peddler. “I am voting for ‘him.’” “For him, who?” “Well, for Trump.” I have a dejá vu that becomes uncanny when a man calls him “el caballo” (the horse, which is the number one in the Cuban numerical charade and used to refer to Fidel Castro). A good number of people do not know which party they are registered with (“It must have been when I became a citizen, that they put that down”), or which one is Trump’s. “Are you with Trump?” they inquire. “With the Democrats,” I respond. “Is that Trump’s party?” “No, it is the other one.” “Oh, we are not interested.” They do not vote in primaries or belong to party clubs. In this election, policy is an afterthought, and many could go whichever way. Theirs is a vote for Donald Trump.

A Vote for Cuba

Many analysts and journalists have attributed this apparent turn-around of new Cuban immigrants toward the Republican Party to Cuban American, Spanish-speaking YouTube sensation Alexander Otaola—a member of the surprise cohort identified by the FIU Cuba poll. Otaola’s daily tirades against the Cuban government, the U.S. Democratic Party, and local “collaborators,” along with his relentless praise for Trump have garnered him an audience of hundreds of thousands. Claiming that Trump’s mano dura (iron fist) will finish off the Cuban regime, while Kamala Harris will “open her legs” to the Communists, Otaola goes a step further: the danger lies not in Cuba but here at home, where the Democratic Party threatens to bring that failed Communism to this shore.

With his high energy style and bling fashion, Otaola has given expression to a younger, social media savvy generation that easily amplifies his message. This is a generation that did not live the Cold War divide that kept Cuban popular culture out of sight and families out of reach. It is a generation that, on the contrary, took advantage of fluid travel, exchanges, and visas to migrate to the United States while still participating in a binational public sphere, also fostered by local media like America TV.

Carlos Otero, for instance, a famous host of the popular Cuban television show Sabadazo, arrived in Miami in 2007 with the promise of employment at America TV, the station known as “Cuban TV in exile.” Like other entertainers from his same age bracket and migratory cohort, now he too is a trumpista. “I voted for Cuba,” said Otero solemnly looking into the camera from his show set on Hialeah Gardens’ America TV, barely a week before the 2020 presidential election. “A vote for Cuba is a vote for Donald Trump.” “True,” seconded comedian Boncó Quiñongo, another Sabadazo transplant and the only Afro-descendant on the staff. “Remember,” continued Otero, directly addressing the audience in Cuba: “During Obama, all eight years, you underwent a lot of hardship. More than today. And today you are also in need, and we are in pain to see our kinfolk in Cuba suffer. This is why I voted for Donald Trump. Because it is a vote for Cuba.”

Yet in 2015, Otero had defended generous immigration policies, penning open letters to both Obama and Trump in support of the Wet Foot, Dry Foot policy that allowed Cubans reaching U.S. land borders to settle in the United States. Now, by contrast, he was supporting the shutting down of remittance channels, a key element in the maintenance of cross-border family bonds. “You can just as well send money through third countries,” advised Quiñongo, apparently unaware that such a thing would defeat Trump’s purpose. For years, both their livelihoods, their show, and their place of employment, America TV, hinged on open circuits of artists, entertainers and popular culture to keep up a local audience eager for a transnational and lively public sphere. But it was time to leave all that behind.

La Buena Vida

Outside the central Hialeah library, a MAGA-hatted man hands me a fanzine in Spanish entitled “The One Percent.” I feign surprise, saying, “Those are the millionaires!” “Like us one day,” he answers. Los 3 de La Habana’s viral video clip comes to mind. There, images of sharply dressed people tossing dollar bills around, young and healthy people partying on a boat, and lines like “How sharp is Melania, with her bag and her dress from Louis Vuitton,” suggest that a vote for Trump is a ticket to living in style. Trump, at minimum, validates an immigrant journey in pursuit of material prosperity that will not be reached through salaried work but through entrepreneurship.

A vote for Trump, thus, may be a vote for Cuba. But above all, it is a vote for America. In this worldview, elections are not about the minutia of policy, but about competing visions of self and the future. The roadmap that Trump offers is uncharted but one thing is certain: It takes Cubans in the United States farther away from the Cuba they left behind. They are new Americans insofar they are also Cubans anew, breaking free from the old country. “Raise your hands if you are both Cuban and American,” sing Los 3 de La Habana. They, having arrived in the United States in 2007, embody the powerful vision of the self-made immigrant that has gained full membership, and for them, Trump makes it possible.

As they recounted in a television interview with Carlucho, another comedian from the same generation and cohort, the pandemic had shuttered their livelihood, giving them no choice other than to apply for unemployment. When an acquaintance hired them to play at a private party, they were warned that the neighbor, a Democrat, might call the police. Their response was a chorus line to playfully provoke him: “I am going to vote for Donald Trump.” Before they knew it, the live feed had gone viral. Trump retweeted it and eventually hired them to play at rallies, while also using their song in campaign ads.

Trump, president of their adopted country, broke through hierarchies to reach down to three new citizens, inviting them to join in the pomp. Political legitimacy might look like it is organized from the top down, but it cumulates from the bottom. Such is the theater of the Trumpian state, and the ideological home that gets out the new Cuban vote.

Ariana Hernandez-Reguant is a cultural anthropologist and a visiting research assistant professor at Tulane University’s Stone Center for Latin American Studies. She is the founder of the HICCUP project (Hialeah Contemporary Culture Project), and has widely published on Cuban and Cuban American political and popular culture. This article is a follow up to her 2016 “Miami Cubans 4 Trump and the Battle for the Nation,” published in Cuba Counterpoints.