This piece appeared in the Spring 2021 issue of NACLA's quarterly print magazine, the NACLA Report. Subscribe in print today!

Even if only psychologically, the beginning of the new year represented a chance to exhale. In the United States, 2020 was tarred not only by Covid-19 and its 350,000 deaths, but also by an ongoing pandemic of state violence, particularly against Black people. Black Americans are twice as likely to die from Covid-19 as their white counterparts, and U.S. police shot and killed 226 Black people last year—twice the rate of white people. The descent into more overt white supremacy sharpened as the presidential contest approached, from Trump openly emboldening the Proud Boys to a militia plotting a coup against Michigan’s governor. Hundreds of migrant children were locked up during the pandemic in guarded hotels—shadowy operations advocates warned endangered minors. Voters rejected Trump’s vision for making America great again (again) by over seven million votes.

Before celebrating the end of Empire, it is worth remembering that over 74 million voters gave Trump their approval, which is more people than had voted for Obama. And President Joe Biden’s ties to the international revolving door between lobbyists and multinational corporations have been long been exposed. And yet, as the January 6 coup attempt graphically underlined, Empire is in crisis, and it is flailing to restore itself by descending into fascism.

On January 1, 2021, Haiti commemorated 217 years of independence. Instead of large celebrations or protests, the streets of Port-au-Prince were notably empty. Some posted videos of tires burning, blockading main thoroughfares, but mostly people were at home out of fear of being kidnapped. Abductions spiked dramatically in the last two months of 2020, coincidentally since the U.S. presidential election. This “gangsterization” has spread into far-flung areas of Haiti such as the Grand-Anse department. In addition to a generalized state of fear, activists have denounced increasing targeting, including legal persecution: President Jovenel Moïse issued a decree last year establishing that certain forms of protest constitute “terrorism.” According to the United Nations Integrated Office in Haiti (BINUH), 944 people were murdered in the first eight months of 2020. Although Moïse’s term expired on February 7, there isn’t even a pretense of an end in sight to the violence or the regime.

In the two oldest nations in the Americas, born of revolution, the processes of state violence in all its forms are symptoms of the structural inequalities of racial capitalism. The two nations also share a history, as the United States transformed into a global superpower as a result of France losing its “pearl of the Caribbean.” The Haitian Revolution and first constitution offered amnesty and citizenship to any person seeking freedom from slavery. Slaveholding powers, particularly the United States, systematically punished Haiti for this precocious assertion that Black Lives Matter. Industrial capitalism was built on Caribbean sugar plantations, which is to say on slavery.

Aside from serving as an example and inspiration for slave revolts across the Caribbean and the United States, newly independent Haiti offered timely assistance to Simón Bolívar in 1815, enabling him to liberate Venezuela, and thus South America, from Europe. This vision of pan-American solidarity outside U.S. control was interrupted in 2019 when Trump ally Moïse severed ties with Venezuela. In exchange for Haiti’s decisive vote against Venezuela in the Organization of American States (OAS), the Trump administration rewarded Moïse with ongoing support. As was the case following a similar OAS vote in 1962 that ejected Cuba from the bloc with Haiti’s support, the U.S. blessing emboldened the Haitian state to consolidate power by any means necessary. History has judged Haitian president-for-life François Duvalier (1957-1971) as a dictator abetted by Washington. Solidarity movements have been slow to come to this same conclusion in the contemporary context.

In other words, the situation in Haiti is directly connected to U.S. Empire. It is at the other end of racial capitalism’s brutal accumulation and the repressive state apparatus necessary to maintain it. To look at the situation in Haiti is to look at U.S. Empire, and vice versa. As Empire’s decline triggers fascist efforts to cling to power, these states sanction ongoing police brutality and paramilitary terror against dissenting Black bodies, embodied in white vigilantes or militias in the United States and neighborhood-based gangs in Haiti. At the same time, both states have rendered women and LGBTQI+ people more vulnerable.

More specifically, in Haiti, since January 13, 2020—a day after the 10th anniversary of the devastating earthquake—President Moïse has ruled by decree. The parliament’s term expired, and general elections remain stalled, currently scheduled for September 2021. The 2011 election of President Michel Martelly and his subsequent consolidation of power in his Haitian Tèt Kale Party (PHTK) gave rise to a bandi legal or “legal bandit” toxic masculinist state that has intensified a culture of rape and impunity. Several government officials, influential media personalities, and notorious gang leaders have been accused of (but not tried for) systematic sexual assault. Neighborhoods known for resisting their organized abandonment have been targets of massacres. Many activists including artists, movement leaders, journalists, legal scholars, and some state officials have been jailed, received death threats, or been assassinated.

Continue reading the rest of the introduction here. Check out the table of contents here.

Mamyrah Dougé-Prosper is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Africana Studies at Davidson College. Her doctoral work centered on a coalition of social movement organizations calling for an end to the ongoing “non-governmental” occupation of Haiti. She is currently working on my monograph entitled Development Contested in Occupied Haiti: Social Movements, NGOs, and the Evangelical State. She has also served as an organizer with land and housing rights organization Take Back the Land-Miami and is presently the International Coordinator for Community Movement Builders.

Mark Schuller is Professor at Northern Illinois University and affiliate at the Faculté d’Ethnologie, l’Université d’État d’Haïti. Author or co-editor of eight books, including Humanity’s Last Stand, he has written over 40 book chapters and peer-reviewed articles and more in public media. Recipient of the Margaret Mead Award and the Anthropology in Media Award, Schuller is president of the Haitian Studies Association and the United Faculty Alliance, NIU’s faculty union.

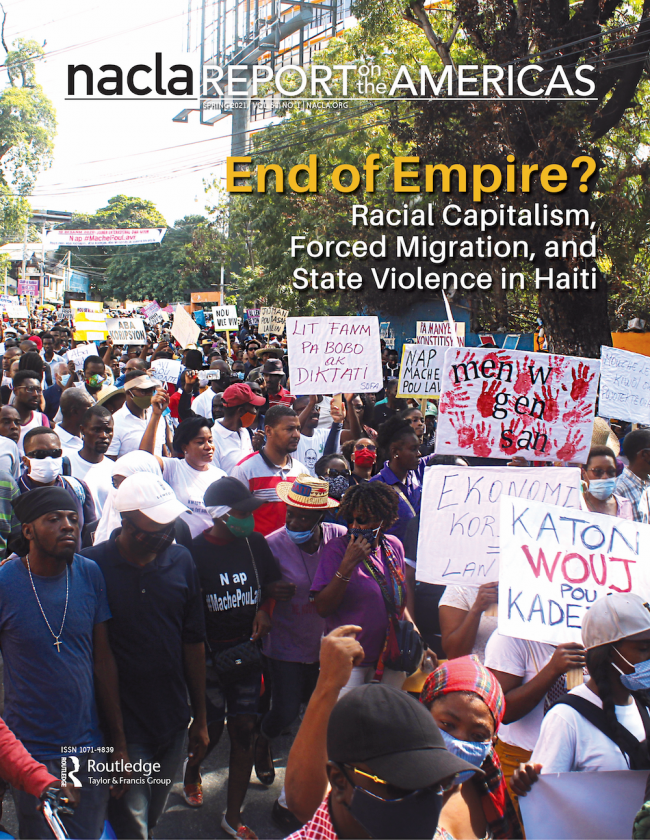

Cover photo by Stephen William Phelps.