Fiscal Year 2010 saw the U.S. government deport a record 392,862 immigrants. Approximately half of them, according to the Department o f Homeland Security (DHS), were convicts—an increase of more than 81,000 “criminal alien” deportations vis-à-vis the G.W. Bush administration’s final year.

f Homeland Security (DHS), were convicts—an increase of more than 81,000 “criminal alien” deportations vis-à-vis the G.W. Bush administration’s final year.

For many, the deportation of dangerous criminals is the main justification—and should be the focus—of the ballooning deportation program carried out by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), a DHS agency. Indeed, President Obama recently bragged that his administration has “increased the removal of criminals by 70 percent,” while emphasizing that Washington is focusing its “resources on violent offenders and people convicted of crimes; not families, not folks who are just looking to scrape together an income.”

a DHS agency. Indeed, President Obama recently bragged that his administration has “increased the removal of criminals by 70 percent,” while emphasizing that Washington is focusing its “resources on violent offenders and people convicted of crimes; not families, not folks who are just looking to scrape together an income.”

An Associated Press (AP) report last week, however, shows that the deportation dragnet is much wider than Obama’s words suggest. In doing so, it illustrates the dangers of embracing the slippery slope of deportation and the immigration enforcement apparatus more broadly—a mistake committed in the name of political expediency by all-too-many advocates championing what is known as “comprehensive immigration reform” (as demonstrated in a very important article by Seth Wessler in Colorlines).

According to the AP, those convicted of drug offenses were the biggest group of crime-related deportees. At the same time, a significant share was comprised of individuals arrested for violating traffic laws or drunk driving. Meanwhile, the number of people deported for immigration-related offenses—e.g. overstaying a visa, entering the country without authorization, or making a fraudulent statement on an immigration application—jumped 78 percent in comparison to two years ago.

For the myriad deportees who were legal permanent residents (a status they lose if found guilty, for example, of most drug offenses or any crime carrying a penalty of one year or more), these numbers illustrate the double jeopardy they face. Convicted immigrants do their sentence, and then, due to ever-more draconian laws, are automatically sent into exile (with few exceptions) regardless of how long they have lived in the United States or the strength of their ties to the country, such as having U.S. citizen children.

The response of many immigrant advocates and analysts to the huge numbers of deportations of individuals convicted of minor legal transgressions is to call upon the Obama administration to keep its promise to focus on the “worst of the worst,” and to devote its energies to deporting the truly dangerous. As the head of the National Immigration Forum, Ali Noorani, for example, stated, in criticizing the federal government for a bloated and wasteful enforcement system and a failure to “fix the broken immigration system,” Washington needs to “adhere to its publicly stated policy of focusing resources on deporting criminals and dangerous threats.”

Such rhetoric helps to legitimate a criminal justice system that imprisons people at a greater rate than any other country in the world, one that sees lawbreakers—especially the low-income and nonwhite—as permanent criminals beyond redemption. It also falls into the trap of making a politically perilous division between good and bad immigrants and thus helps to legitimize the ever-growing apparatus of immigrant regulation and exclusion. Moreover, it validates banishing individuals from “our” territory while making a simple distinction between “us” (those of who benefit from an accident of birth) and a less-deserving “them.”

In Sentenced Home, a remarkably illuminating and heart-wrenching documentary (see trailer below) that follows three young Cambodian-American men from the Seattle area as they negotiate the deportation process, Patricia Vroom, a Chief Counsel for ICE, articulates the underlying logic: “The issue is . . . what are the rules that people who have been given the right to live in this country must follow in order to get to stay here? And there’s something of a quid-pro-quo. We’re giving you something of tremendous value. And in exchange for that we expect you to do nothing more than live like all people who got this for free. That’s all. That’s all we’re asking. And if you can’t do that, we’re going to have to take it away from you.”

Of course, what “we’re asking” of “people who have been given the right to live in this country” is not to “live like all people who got this for free.” Instead, we’re holding “them” to a different standard than “us,” and if they fail to meet it they will face a set of sanctions that simply don’t apply to citizens—exile being the worst among them.

In carrying out the deportation regime, we erase the fact that many, if not most, of the deportees are far more U.S. American than they are some other nationality given their often tenuous-at-best ties to their country of birth. We also obscure U.S. responsibility for helping to create the conditions that drive the now-unwanted immigrants from their former homeland—Cambodia being just one example of many.

While justified in the name to public safety—even though immigrants as a whole, and unauthorized immigrants in particular, are significantly less likely to commit crimes than native-born U.S. citizens—the system of deportation first and foremost is about the inherently inhumane process of nation-state-building, one that necessitates, especially in a world of profound socio-economic inequality, violent exclusion of various sorts.

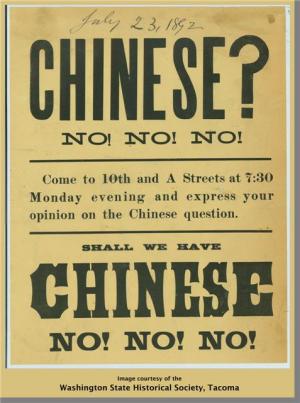

Whether it be the supposed dangers of Chinese immigrants in the late 1800s, “communists” and “anarchists” in the early decades of the twentieth century, or “terrorists” and “criminals” today, the U.S. exclusion regime has focused its gaze and grip on the antithesis of what dominant groups in this country define as “American.”

Whether it be the supposed dangers of Chinese immigrants in the late 1800s, “communists” and “anarchists” in the early decades of the twentieth century, or “terrorists” and “criminals” today, the U.S. exclusion regime has focused its gaze and grip on the antithesis of what dominant groups in this country define as “American.”

It is highly questionable at best if the system does anything to enhance the wellbeing of U.S. society as a whole—especially for its most marginalized members. What is irrefutable is that it helps to cause great pain and suffering within families and communities across the country.

Such a system is not “broken.” It is fundamentally unjust, and thus needs a lot more than reform.