This article was originally published in Spanish in Revista Común.

Translation by Liza Schmidt.

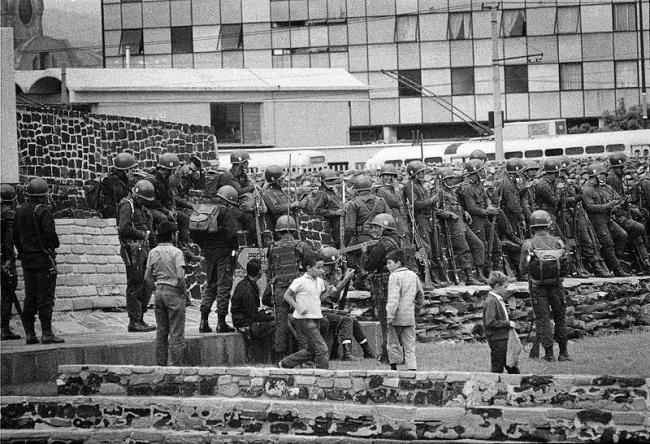

A year ago, Revista Común published a section of Sergio Aguayo’s book reviewing the events of the Tlatelolco Massacre on October 2 and how the CIA contributed to them. This text explores the CIA’s actions in various universities, especially the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), during the 1960s.

Reviewing the CIA’s operations in the 1960s through Mexico offers a privileged point of observation for two reasons: first, the fact that Lee Harvey Oswald traveled to Mexico City a few weeks before assassinating John F. Kennedy in 1963 has allowed several investigations to make public the CIA’s files on our country. Secondly, the CIA officer assigned to the Olympic Games in 1968, Philip Agee, quit shortly after and published a book, Inside the Company (1975), on his work in Latin America.

The U.S. Congress’s deadline for publishing all the government files in their entirety related to the assassination of JFK passed in October 2017. Although President Donald Trump blocked the declassification of many documents, some new documents emerged in which names or previously redacted lines now appeared, providing new facts and confirming many suspicions.

In the ‘60s, the CIA station in Mexico City established an extensive espionage network including photo surveillance, wiretapping, and undercover operations without the Mexican government’s knowledge. At the same time, the CIA carried out a joint operation with the Mexican government through which they received all kinds of support from government officials, the office of the president, and the Mexican secret police and intelligence agency, DFS, in exchange for dollars. The code name for that joint operation was LITEMPO.

The CIA assigned this type of code name, or cryptonym, to its agents, operations, and the various political actors they worked with. The code names included two letters that indicate the location or general category, followed by a word or more letters. The ones that correspond to Mexico start with “LI.” The Mary Ferrell Foundation created a useful catalogue of these code names.

When violent groups known as “porros” began to appear in marches or on campus at Mexican universities, it raised the questions, what political force is behind them and how are they directing them? Guillermo Sheridan has written about a series of student groups managed by the CIA. The most well known of the groups was Movimiento Universitario de Renovadora Orientación (MURO), a rightwing Catholic group that was the student arm of the fascist organization, los Tecos. MURO’s code name was LIEVICT and the group’s leader was in regular contact with the CIA, according to a memo signed by Willard C. Curtis, the pseudonym used by Winston C. Scott, who was the CIA station chief from 1956 and 1969. LICOAX and LILISP-C were other active student groups in Mexico City used by the CIA for political purposes.

The relationship between the CIA and MURO also involved businessman Alfonso Rudolph Wichtrickh (LIHUFF-1), manager of Royal Crown Cola who, during WWII worked in military intelligence, and Agustín Navario (LIHUFF-2), director of the anti-communist Institute of Social and Economic Research. Wichtrich was responsible for organizing and directing the student groups, as well as planning and instigating attacks on university students. He was also the vice president of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in Mexico and received $500 a month—the equivalent of $4,500 today—from the CIA. On August 26, 1966, with the blessing of the U.S. ambassador, the CIA sent a group of porros to attack an exhibit of communist Chinese art in the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters at the UNAM.

According to Agee—who enrolled as a postgraduate in Latin American Studies at the UNAM after leaving the intelligence agency—the CIA planned psychological and paramilitary operations against members of the communist party, creating propaganda, spreading false information, incriminating party members, coordinating repressive measures with partners like the DFS in Mexico City, and directly organizing porros. He adds that these groups, which sometimes included off-duty police officers and supporters of allied political parties, intimidated communists and other leftists by crashing their meetings and demonstrations.

To break up meetings, Agee says the CIA used a range of weapons and devices out of a science fiction movie: vials of foul-smelling liquids, flavorless substances that could be added to food and cause physical discomfort, or itching powder administered to flyers or toilet seats. A DFS report in the General Archive of the Nation offers one example of this arsenal in action: in 1961, a stink bomb was set off in the Mexico-Cuban Institute to prevent a conference by philosopher and UNAM professor Luis Villoro. The Cuban embassy staff cleaned the room with deodorizing spray and the conference continued with an audience of 50 people. The report was signed by three DFS agents, including Miguel Nazar Haro, who became the head of the DFS in 1978, raising doubts about how many of the audience members were actually spies.

A few years later, another CIA cable boasted that they’d gotten three marxist university heads fired from the Nuevo León, Puebla, and Morelia universities within a few months. The cable reported that the first case, in Nueva León, was the result of a long campaign against the dean orchestrated by the CIA station in Monterrey. In the cases of Morelia—where Elí de Gortari was dismissed—and Puebla, CIA agents and student groups coordinated on the slander campaigns, which “were financed and materially supported by LIHUFF, LISIRE, LICOAX, and LILISP C.”

Among the new documents that appeared in 2017 is a report of nearly 200 pages about the LIHUFF operation that commanded the MURO student group at UNAM, with dates through October 1971. The report includes a March 11 cable describing how the CIA station could covertly incite MURO student demonstrations at a cost of $1,200-1,600 using CIA-designed posters and banners that could not be traced back to them. The station had previously organized successful demonstrations with “poorer Mexicanos” who had been individually paid posing as rail workers.

The same report contains another cable from August 24 mentioning that station chief Scott was providing funds and plans to LITEMPO-4, the code name for DFS director Fernando Gutiérrez Barrios, to protect the LIHUFF-1 operation and hide U.S. interference. It explains that MURO covered the city in flyers encouraging people to protest. Finally, in a footnote, the report adds that the station had the ability to increase the number of MURO protestors in front of the Soviet Embassy to 5,000 for a fee of $4,000 via LITEMPO-4. This was six weeks before October 2.

One of the most important internal documents on this topic is the history about the CIA station in Mexico from 1947 to 1969, written by CIA officer Anne Goodpasture, who was the right hand to Scott. Since the end of the ‘70s, about 200 pages of this text have been made public. In the most recent version, names and dates that were formerly redacted have been revealed. Goodpasture mentions that among the students detained by the army in Tlatelolco there was an undercover CIA agent, LIEMBRACE-4, who was freed a few days later.

After this passage there are ten blank pages. Already more than half of the document has been removed, so why were these ten pages included and completely censored? And why do they remain blank even after the release of data in 2017? An appendix to the document mentions that the missing section concerns undercover student operations. Is it possible that these blank pages have more information about the role of the CIA in the events leading up to October 2 as well as what happened that day?

A new phase of declassification will begin on October 26. It remains to be seen what documents and sections appear and whether they will include these blank pages. If not, the blank pages will remain a mystery that fuels our suspicions and theories.

Gonzalo Soltero is an author and professor at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) in ENES León, Guanajuato. He has published five books of fiction and several peer-reviewed articles. His research interests include the impact of narratives upon culture, conspiracy thinking and subjective well-being.