Visibly moved, President Barack Obama offered heartfelt words in the aftermath of the tragic events in Newtown, Connecticut in mid-December. He suggested that all of us in the United States should “hug our children a little tighter and . . . tell them that we love them.”

In doing so, he made clear that his expression of love was not limited to his biological children. Referring not only to the young people killed in the Newtown elementary school, but also to those slain in “a shopping mall in Oregon or a temple in Wisconsin or a movie th eater in Aurora or a street corner in Chicago,” he asserted that “These neighborhoods are our neighborhoods, and these children are our children.” In other words, love at its best can and should be expansive, not confined by the boundaries of space and time.

eater in Aurora or a street corner in Chicago,” he asserted that “These neighborhoods are our neighborhoods, and these children are our children.” In other words, love at its best can and should be expansive, not confined by the boundaries of space and time.

It was hard not to think of these words two days after they were uttered when reading an article by Seth Freed Wessler in Colorlines.com about the impact on children of the Obama administration’s deportation dragnet—one that “removed” even greater numbers of people in Fiscal Year (FY) 2012 than in the previous record-setting year. The federal government, states the article, “conducted more than 200,000 deportations of parents who said their children are U.S. citizens in a timespan of just over two years.”

While certainly costly to immigrant families and communities, the deportations also exact a high financial cost to the federal government—as does the larger apparatus of immigration and boundary control. According to a report issued earlier this week by the Washington, D.C.-based Migration Policy Institute and that garnered considerable attention, the budget of what it characterizes as a “well-resourced, operationally robust, modernized enforcement system” has reached record levels.

In Fiscal Year 2012, spending on U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), the parent agency of the Border Patrol, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and a biometric tracking system called U.S.-VISIT totaled almost $18 billion. This staggering sum is approximately 24% greater than the combined budgets in the last fiscal year ($14.4 billion) of the FBI, Secret Service, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), the U.S. Marshals Service, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF).

on U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), the parent agency of the Border Patrol, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and a biometric tracking system called U.S.-VISIT totaled almost $18 billion. This staggering sum is approximately 24% greater than the combined budgets in the last fiscal year ($14.4 billion) of the FBI, Secret Service, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), the U.S. Marshals Service, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF).

While there are many ways by which the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and its champions justify such levels of spending, one is by invoking the well-being of children. ICE’s “Operation Predator,” for instance, “targets and investigates child pornographers, child sex tourists and facilitators, human smugglers and traffickers of minors, criminal aliens convicted of offenses against minors, and those deported for child exploitation offenses who have returned illegally.”

Whatever the merits and demerits might be of such an initiative—one that ICE frequently touts in its extensive public relations efforts—the resources that go into it pale in comparison to those invested in breaking up families via deportation. Nonetheless, DHS uses endeavors such as Operation Predator to mask how it polices families and children.

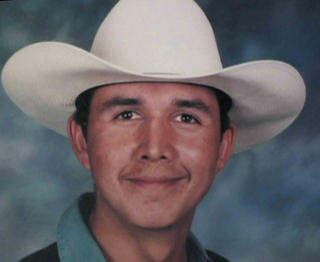

Presidio County, Texas, which abuts the U.S.-Mexico divide, has long been at the epicenter of such efforts. It was there—in the tiny town of Redford specifically—that a U.S. Marine, Clemente Manuel Banuelos, mistakenly, and perhaps criminally, shot and killed 18-year-old Esequiel Hernández Jr while he was herding his family’s goat on May 20, 1997. Banuelos and his fellow Marines were there to monitor individuals smuggling drugs from Mexico across the Rio Grande.

Recently the drug war took a new turn in Presidio County. There, the U.S. Border Patrol began inspecting school buses in the area for contraband when they pass through the agency’s highway checkpoints. Previously, school buses had been exempt from such inspections, but the Border Patrol changed its policy after almost 500 pounds of marijuana were found hidden on a bus.

The Border Patrol has promised to undertake the inspections in a careful manner, and not to ask students about their immigration status. “Our objective is the safety of the children,” Chief Patrol Agent John Smietana told a meeting of local school officials.

The federal government has seemingly endless amounts of resources to police and “protect” children—but only in very select ways. This in a country where about 16 million children live below the poverty level.

As Enrique Madrid, a local historian in Redford, Texas asserts in the documentary film, The Ballad of Esequiel Hernández, “Presidio County is one of the poorest in the State of Texas, one of the poorest in the nation, and South County is the poorest part of that poor county. And yet they send us Marines instead of educators. They send us Border Patrolmen instead of doctors.”

More than 15 years after the tragic killing of Esequiel Hernández, Washington’s misplaced priorities have become only more pronounced. How the ruling class effectively defines the boundaries of the well-being of children has become increasingly narrow and harmful—in Redford and throughout the borderlands.

Joseph Nevins teaches geography at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York. Among his books are Dying to Live: A Story of U.S. Immigration in an Age of Global Apartheid (City Lights/Open Media, 2008) and Operation Gatekeeper and Beyond: The War on “Illegals” and the Remaking of the U.S.-Mexico Boundary (Routledge, 2010). For more from the Border Wars blog, visit nacla.org/blog/border-wars. Now you can follow it on Twitter @NACLABorderWars.