If anyone had any doubts that the struggle to save Chican@ Studies is separate from immigration and border enforcement issues, the cross-section of the community that turned out to a board meeting of Pima Community College in Tucson, Arizona back in February should have shattered those doubts. The associated efforts are now on the brink of a monumental victory for education and cultural rights.

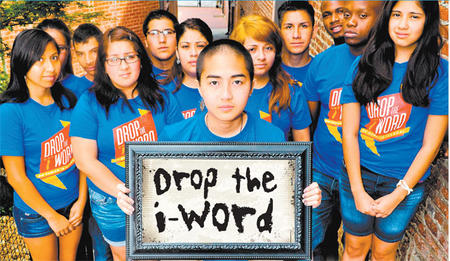

A source on the Board of Governors at Pima, an institution with a large undocumented student population, reports that they are close to a deal with students from within and without the institution. The deal would make Pima the first known U.S. college or university to drop the ‘i’

word (i.e. using “illegal” to describe human beings) from inside classrooms. Although other post-secondary schools administratively use “undocumented” over “illegal,” Pima’s case challenges the term “illegal” within classroom curricula.

The campaign to drop the ‘i’ word has already scored significant success in the media. After two years of national advocacy by immigrant rights groups, The Associated Press made headlines recently when editors finally decided they would no longer use “illegal immigrant” to describe people of various immigration statuses. Youth efforts calling on their school to drop the ‘i’ word, gaining ground in Tucson, Arizona, would mark an unprecedented breakthrough in the U.S. educational sector. Recent news of “immigration reform” (that includes a more than 10-year path to citizenship restricted to “illegal” immigrants who arrived in the United States before 2011) only underscores the importance of such a victory.

It all started at the February 27 board meeting. A local DREAMer group, Scholarships A-Z, had long been advocating for a resolution (approved by a landslide that night) allowing undocumented students to pay in-state tuition and access scholarships just as anyone else, regardless of immigration status. The DREAMers had mobilized a massive support base of families and local organizations that came out in full force to back the youth.

One such group of supporters is UNIDOS (United Nondiscriminatory Individuals Demanding Our Studies), a youth coalition formed in 2011 to save and expand the only K-12 program of Chican@ studies in the country, outlawed by Arizona state authorities in 2010.

UNIDOS gained national attention in April 2011 when nine youth members chained themselves to the Tucson Unified School District (TUSD) board members’ chairs and dais to stop a vote that would have eliminated the country’s only K-12 Mexican-American Studies program.

Three fellow UNIDOS members and I (spanning from high school- to college-age) spoke during the Call to Audience section that night. During our speech in front of the board, we noted facial expressions of abject shock among some board members as we recounted stories of harassment by authorities outside the campus confines. It was the way these stories impacted us as Pima students within the classrooms, however, that we urged the board to heed closely and act upon.

Although language is not made of “sticks and stones” as it were, language can dull or sharpen the instruments of repression. Language plays a main role in the dynamic between the “motivating passions” (culture) of the nation and political and economic issues, particularly those represented by state policy. After all, as sociologist Hugh Mehan points out: “The language we use in public discourse and the way we talk about events and people in everyday life makes [sic] a difference in the way we think and the way we act about them.”

UNIDOS member Arturo Duran’s story was specially compelling on this point. Last June—shortly after President Obama’s promise to halt deportations of DREAM-eligible youth—then 19-year-old Duran and his family got the nightmare of a lifetime. While driving in Marana, near Tucson, Arturo was pulled over by a local Pima County sheriff’s officer. When asked for documentation, Arturo could only show the officer his Pima school I.D. In compliance with the now nationally-sanctioned SB 1070 law, the sheriff called Border Patrol, whose agents came and picked up Duran, and placed him in immigration detention overnight.

As Arturo told the Pima board that night, “My Pima I.D. card wasn’t good enough for the officer of the Sheriff’s department who stopped me and called Border Patrol agents who then threw me into a detention facility this past summer. But I do expect my college’s institutional culture to be good enough to be free from harassment in viewing me as an ‘illegal’ human being.”

We as UNIDOS representatives gave the board until the following week to enter into negotiations with us over the conditions and a timetable for dropping the ‘i’ word from the institution, including updating Pima’s anti-Hate Speech and anti-Harassment policies.

Challenging the ‘i’ word comes at an opportune time in history, I told the Pima board  back in February. Like the ‘n’ word, for a long time, the word ‘illegal’ was unassailable because it was too entrenched in American society. But now nationwide many people are organizing anti-harassment efforts to challenge it. In this way, the ‘i’ word today is at a comparable historical place that the ‘n’ word was by the late 1930s.

back in February. Like the ‘n’ word, for a long time, the word ‘illegal’ was unassailable because it was too entrenched in American society. But now nationwide many people are organizing anti-harassment efforts to challenge it. In this way, the ‘i’ word today is at a comparable historical place that the ‘n’ word was by the late 1930s.

Scholarships A-Z organizer Allie Salazar felt “overjoyed” that night, tears dampening her face as the board voted overwhelmingly in favor of the proposal she and her community fought so long and hard for. But, as she told us in UNIDOS, this is just the beginning.

“There’s still a lot more to be done to help our undocumented youth,” she said.

The current campaign urging Pima Community College to drop the ‘i’ word is one indicator of the ongoing movement for migrant justice in the United States. Now, the so-called “immigration reform” that appears to be on offer is a sign of more challenges to come, given that the root causes (political and economic factors) of migration remain unaddressed.

In other words, the struggle over language revealed at Pima represents citizen and noncitizen youth alike fighting for the rights of those for whom the future holds no “path to citizenship” but more stigmas of “illegal.”

Students are fighting for the future now. Because we won’t settle for anything less.

Gabriel M. Schivone is an alumnus of Tucson High School and has been a member of UNIDOS since 2011.