Chicago's spatial landscape has been home to numerous multiethnic and transnational communities over the centuries. Very seldom is the Mexican experience part of this story in the Midwest, let alone the legacy of the third-largest city in the United States. Mike Amezcua's Making Mexican Chicago: From Postwar Settlement to the Age of Gentrification centers Mexicans within the historical narrative of the Windy City as community builders and placemakers. The "Mexicanization of Chicago" was formed through pitched political battles, civil rights protests, and calls for urban reform to fight against segregation, immigration policy, and urban displacement in the contested neighborhoods of the Near West Side, Pilsen, Back of the Yards, and La Villita.

Chapter One, “Crafting Capital,” recreates the physical reality that many Mexican Chicagoans encountered. In the early 20th century, the city became a laboratory for Homer Hoyt’s racial and ethnic neighborhood property value ranking system. Hoyt’s system was a precursor to the New Deal’s security maps enlisted by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation and Federal Housing Administration during the Great Depression, a measure that became known as redlining. In Chicago, Hoyt’s initial ranking system was the first to identify Mexicans as a residential racial class linked to property devaluation. As white residents moved to nearby suburbs, ethnic Mexicans faced the reality that they could not move outside segregated neighborhoods due to restrictive racial deed covenants. Mexicans were also concentrated in the inner city, where they could find housing—although segregated—near manufacturing and packinghouse jobs that paid well. As Chicago began deindustrializing in the mid-20th century, however, these employers moved to other parts of the country, leaving Mexican workers and communities without reliable means of employment. These actions resulted in their concentration in urban colonias with limited political representation, substandard housing, urban renewal schemes, gentrification policies, and the onslaught of the U.S. immigration regime.

In Chapter Two, “Deportation and Demolition,” Amezcua examines the effects of immigration policy and U.S. slum clearance causing mass displacement and deportation of ethnic Mexicans in the Near West Side in the post-war period. The McCarran-Walter Act of 1952 and Operation Wetback in the 1950s ushered in new immigration strategies that surveilled and deported Chicago Mexicans. Although Chicago is removed from the U.S.-Mexico border, Amezcua demonstrates that the policing of Mexican bodies in the United States was an endeavor that extended into the Midwest. In the ruins of deindustrialized factories, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) and Border Patrol created deportation facilities meant to apprehend and confine Mexican immigrants. In Chicago, the INS's goal during Operation Wetback was to apprehend and deport “twenty-five thousand to forty thousand undocumented immigrants.” Amezcua explains that INS records do not indicate if this goal was ever met. Yet, the record of deportations by airplanes out of Chicago cataloged over 11,000 deportations between 1954 and 1955.

The INS weaponized segregated Mexican neighborhoods by targeting them for deportation campaigns. These neighborhoods were considered blighted, and Mexicans were also labeled transients and aliens. However, Near West Siders actively combatted their perceived illegal status by participating in Chicago politics and urban renewal movements through community-based planning. Among them was Anita Villarreal, the first Latina licensed real estate agent and political broker who in the 1950s advocated for neighborhood preservation and ensured that Mexican residents could purchase property in these communities. In time, Near West Siders were quickly displaced as they became targets of slum clearance to create the University of Illinois Chicago campus.

In Chapter Three, “From the Jungle to Las Yardas,” Amezcua examines racial coalitions and divisions in Las Yardas, the neighborhood written about in Upton Sinclair’s book The Jungle. After World War II, racial animosity and white flight to new suburbs intensified in Chicago. Mexican Back of the Yarders, as Amezcua identifies these neighborhood residents, operated in an urban borderland that allowed them to purchase property between white and African American neighborhoods like Bronzeville. Mexican Back of the Yarders actively created community spaces through storefronts, renovating dilapidated buildings, and religious institutions like Immaculate Heart of Mary Vicariate.

Back of the Yarders worked alongside notable organizer Saul Alinsky to create a community action group comprised of a coalition of white and Brown residents and packinghouse workers to fight against class and labor issues within the neighborhood. Alinsky, with organizations like the Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council (BYNC), tried to convey a sense of racial unity and cultural pluralism between the groups, but those alliances only went as far as organization and mobilization efforts. Racial segregation in Chicago persisted, and white residents continued to speak out publicly against Brown and Black residents moving into white neighborhoods even as they were forcefully being displaced by slum clearance. In calls for neighborhood preservation and conservation, local institutions such as the University of Chicago Settlement House, later known as the McDowell Settlement House, collected community support against urban renewal in the Back of the Yards. Still, major organizations like the BYNC reinforced the color line by supporting white residents’ efforts to prohibit public housing and the selling of homes to Black and Brown residents.

In Chapter Four, “Making a Brown Bungalow Belt,” Amezcua examines the collective effort by ethnic Mexican and African American leaders to organize against segregated real estate markets and urban renewal. The Pilsen neighborhood witnessed an influx of Mexicans that sparked a new wave of Brown suburbanization. Fearing the shifting neighborhood demographics, realtors encouraged white residents to sell their property and move into other neighborhoods. With the community in mind, local ethnic Mexican realtors created a third housing market that bought and sold houses to Mexican residents looking to secure well-kept affordable housing with lawns and living space for growing families. Local organizations like the Illinois Federation of Mexican Americans (IFOMA) organized to relocate and support Mexican residents amid local white political opposition.

During the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, South Lawndale rebranded itself as Little Village and overhauled its urban aesthetic to prevent further white flight. However, over time Little Village transformed into La Villita, a thriving ethnic Mexican enclave with substantial political power, Mexican real estate acquisitions, and community institutions. As white councils sought to reinforce the color line, leaders like Anita Villarreal—who was once again displaced—moved into the neighborhood and instantly became a La Villita power broker by gaining the attention of Mayor Richard Daley. The political power enlisted by La Villita and spearheaded by Villareal allowed for the first Mexican American judge to be appointed to the city.

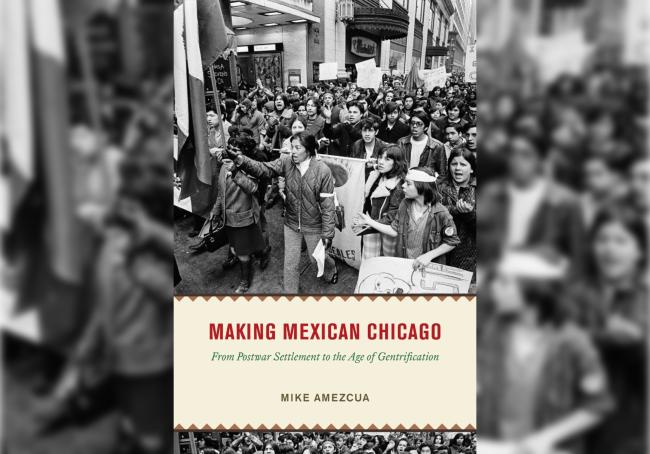

Chapter Five, “Renaissance and Revolt,” examines how ethnic Mexicans dealt with the changing political, social, and built environment in Chicago from the 1960s-1970s. Overcrowded neighborhoods like Pilsen had reached new poverty levels, pushing residents to call for further political participation and funding for education and healthcare. The Chicano Movement ushered in government oversight to try to resolve community issues. During the period, residents had redirected their support for Daley’s mayoral administration into more radical civil rights politics and others directed toward the Republican Party. During Daley's fifth term in office, he enacted Chicago Plan 21 in 1973. The downtown redevelopment plan was meant to renovate the central city by using urban renewal to condemn and remodel older buildings to create luxury condominiums and a central business district connected through a highway system. Instead of supporting policies like the Chicago Plan 21, ethnic Mexicans partook in community-based approaches to placemaking and servicing neighborhoods, such as creating Casa Aztlan and new Chicano murals across Chicago-based Mexican communities. These new institutions and artworks profoundly impacted residents and created a community renaissance of activism and ethnic empowerment.

The following chapter, “Flipping Colonias,” discusses the onset of gentrification in Chicago Mexican colonias. From the 1970s-1990s, South Chicago used grassroots mobilization and organization efforts to push back against gentrification. The new colonization of urban America translated to revitalization and economic development that paralleled the growth of ethnic Mexican populations. Developers like John Podmajersky embarked on a mission to transform Pilsen into an Art Colony, citing the neighborhood’s unique architecture and character. Measures like this only reinforced previous misconceptions about Mexicans as a transient class with limited roots in the neighborhood, not considering their decades-long residency and organizing. Ethnic tourism became another method by city officials to showcase the uniqueness of Pilsen even as Mexican residents protested against it.

In the 1980s-1990s, calls for cultural nationalism and youth activism for civil rights and against displacement changed as a new Latinx culture grew in Chicago. Members of this cultural shift included writer Sandra Cisneros, the punk rock scene, and new wave music crews. In the political arena, Mayor Richard Daley’s neoliberal agenda sought to reinvigorate the Latinx voting bloc in Chicago around significant issues that included suburban housing and bringing affluent residents back to the inner city. This represented another push-and-pull factor that tried to resettle Chicago Mexicans outside the barrios they helped create throughout the twentieth century.

Amezcua shows the multigenerational roots that ethnic Mexicans have in Chicago and how politics, immigration policy, segregation, civil rights, and urban reform all contributed to the placemaking of their communities. The fresh analysis adds to the already growing canon of historical works that examine Latinx communities in Chicago by historians such as Lilia Fernández, Deborah Kanter, A.K Sandoval-Strauss, and Felipe Hinojosa. Making Mexican Chicago provides a foundational approach to the ever-growing field of Latinx Urbanism that analyzes the Latinx community not as a monolith in American society, but as a changing and dynamic force in urban environments like the Windy City.

Dr. Gene Morales is a Lecturer of History at El Paso Community College-Mission Del Paso. His research focuses on Latinx civil rights, urban policy, and borderlands history in the twentieth century. He has written for The Journal of South Texas, The Journal of Southern History, and The Washington Post.