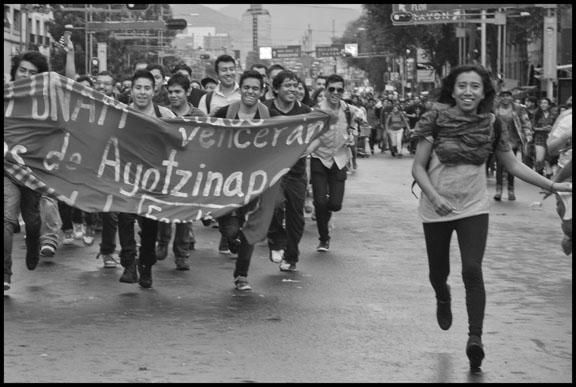

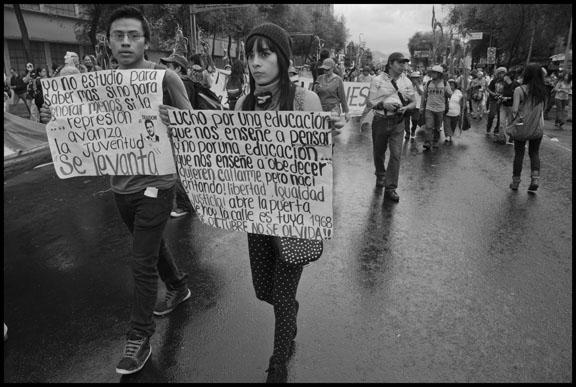

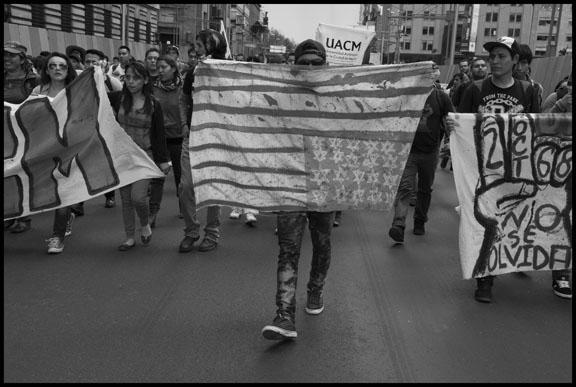

Every year on October 2 thousands of Mexican students pour into the streets of Mexico City, marching from Tlatelolco (the Plaza of Three Cultures) through the historic city center downtown, to the main plaza, the Zócalo. They're remembering the hundreds of students who were gunned down by their own government in 1968, an event that shaped the lives of almost every politically aware young person in Mexico during that time.

This year, just days before the march, the municipal police in Iguala, Guerrero, shot students from the local teachers' training college at Ayotzinapa. More demonstrations and marches are taking place all over Mexico, demanding that the government find 43 students still missing. Many speculate that graves found in Iguala contain their bodies—murdered by the same police, acting as agents of the local drug cartel. Students marching on October 2 were in the streets for them as well, aware that the bloody events of 1968 were not so far away in some distant past.

Raúl Álvarez Garín was one of those whose world changed at Tlatelolco. He was a leader of the national student strike committee, organizing campus walkouts and street mobilizations through the spring of 1968. This rebellious upsurge was simultaneous with student protests in France, the United States and, it seemed then, the whole world. In Mexico it culminated in a huge rally at Three Cultures Plaza.

The Mexican government was preparing for the Mexico City Olympics that year. It had never tolerated political dissent beyond very narrow limits, but then it was even more defensive than usual, fearing any social movement that appeared to challenge its hold on the country's politics. The authorities decided to bring out the army and shoot the students down.

Somehow Álvarez survived the bullets in the plaza, and was then shut into a cell in the notorious Lecumberri prison for two years and eight months. He died two weeks ago on September 27, having spent a lifetime trying to assign responsibility for the decision to fire on the crowd. There was actually no mystery about it. The orders for the massacre were given by then-Secretary of the Interior (Gobernación) Luis Echevarria. But Echevarria was acting for Mexico's political establishment, organized in the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). Álvarez wanted the crime acknowledged publicly and the guilty punished. By spending the next half-century pursuing that goal, he became not just a hero to the Mexican left, but its conscience.

Álvarez was already a man of the left when he got to Tlatelolco. He'd joined the Young Communists, but then left before 1968. He married María Fernanda Campa, daughter of Valentín Campa, one of Mexico's most famous radicals who lived underground and went to prison after leading a railroad workers strike in 1958. After his release, Campa became the 1976 presidential candidate of the Mexican Communist Party, before it merged with other parties and eventually disappeared.

Later in life it was hard to imagine Álvarez as he was described by friends in ‘68—a skinny intense youth of 27. When I met him in 1989 he was already a man of substantial girth. We'd go to lunch with his brother, economist Alejandro Álvarez, and spend hours talking politics. Raúl would get animated, talking beneath his huge mustache faster than my broken Spanish could keep up. He'd ask a hundred questions about Mexicans and unions in the U.S., and we'd plan articles for the newspaper he edited, Corre la Voz (Spread the Word).

Álvarez believed that words have power. Long before Corre la Voz, he started another famous Mexican leftwing journal, Punto Crítico, with other 1968 veterans. His goal was to make his politics accessible to ordinary people, not to inspire debate among dogmatists. "He put our debates into context and showed their limits," remembered Luis Navarro, now an editor at Mexico's leftwing daily La Jornada. "His language was always understandable."

Through the years after 1968 he supported every worker's fight that seemed capable of improving conditions, but that also challenged the political order. As Mexico's political structure began to change in the 1980s Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas ran for President in 1988, against the PRI his father had founded 40 years earlier. Álvarez and others saw the Cardenas campaign as an opening to wrest power from the PRI, 20 years after Tlatelolco. As the votes for Cárdenas were being counted, and it was clear he was winning, the election computers suddenly went down. When they came back up the next morning the PRI candidate, Carlos Salinas de Gortari, one of the country's most corrupt politicians, was declared the winner.

During and after that campaign, many currents of the Mexican left came together and organized the Democratic Revolutionary Party. Álvarez was a founder. He began to look for a way to break workers and unions free of the PRI, to give the new party a working-class base. I met him that year after the election, when I came to Mexico with other U.S. trade unionists. The North American Free Trade Agreement was already on the horizon. Raúl and Alejandro Álvarez were some of the first people who saw the advantage of cooperation in trying to fight it on both sides of the border.

I was beginning to work as journalist north of the border. Raúl and Alejandro helped me understand that for all of NAFTA's disastrous impact on the workers of my country, the trade agreement would have much worse consequences in Mexico. I spent last week as a judge in the Permanent People's Tribunal investigating the causes of migration from Mexico to the United States and the terrible violations of the rights of migrants in both countries. It's clear that if anything, they underestimated the damage. And repression in Mexico is not just a thing of the past. As we met as judges in the Permanent People's Tribunal, just days after Raúl Álvarez died, we heard testimony about yet other mass killings—of 73 migrants killed and buried in the desert in northern Mexico, and the discovery of 193 more in 47 graves less than a year later.

The PRI finally lost the Presidency in 2000, although not to the left but to the rightwing National Action Party. Nevertheless, Álvarez believed it might be possible to get a new government, even a conservative one, to call the murderers of 1968 to account. A new office was created, the Special Prosecutor for Social and Political Movements of the Past. Álvarez, Felix Hernández Gamundi and Jesus Martin del Campo filed a legal case against Echevarria over the Tlatelolco massacre, the killings of other students in a street protest in 1971, and the "dirty war" in which the Mexican government targeted leftists for assassination through the rest of the 1970s.

Formal charges were finally made against Luis Echevarria Alvarez and Luis Gutierrez Oropeza for the Tlatelolco murders, and Mario Moya Palencia and Alfonso Martinez Dominguez, among others, for the 1971 attacks. In the end, however, these former functionaries were able to avoid trial after invoking legal technicalities challenging the ability of prosecutors to indict them. In reality, the political system itself was reluctant to unearth a network of responsibility that would have spread to include many others. Nevertheless, Raúl Álvarez and his two co-complainants felt their work made plain to the Mexican people the terrible acts of repression that had cost many lives, and who had given the orders for them.

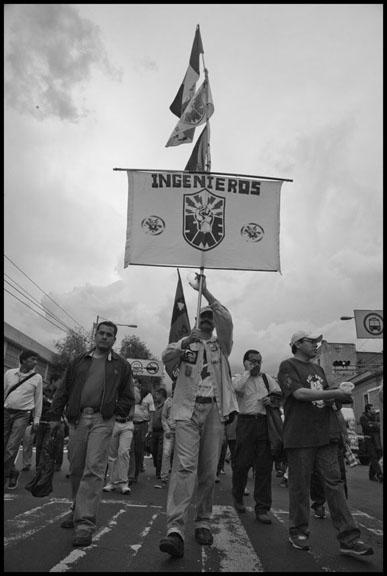

Bringing up the rear of the October 2 march were members of the only union visibly present—the Mexican Electrical Workers (SME). Both Álvarez and this union have been anchors of left wing politics in Mexico City. For twenty years the SME campaigned to stop the Mexican government from turning over the nationalized oil and electrical power industries to private corporations. To neutralize its opposition, the SME's 44,000 members were fired five years ago. The PAN administration of Felipe Calderón ordered the army to occupy the generating stations and declared the union "non-existent." When the PRI came back into power last July, it pushed through a constitutional amendment permitting the privatization.

Raul would have pointed out that there is really no difference between the pro-corporate policies of PRI and PAN. He fought to keep parts of the PRD from supporting the same privatization reforms. Just days before his death, a delegation of SME leaders went to his home in Mexico City, and gave him a union card, making him member #16,600. He told them he was proud to be a member of this "union in resistance."

Raul Alvarez' photograph, taken on another October 2 march a few years earlier, was carried as the banner at the head of the marchers this year. If he'd been alive, he would undoubtedly have been there in front himself.

David Bacon is a photojournalist, and has been a labor and immigrant rights activist for four decades. He's the author of four books, the latest of which is The Right to Stay Home (Beacon Press, 2013).