“I thought that it was raining,” education students wrote the day after police killed as many as 12 and injured dozens at protests in the majority- indigenous southern Mexican state of Oaxaca on June 19. “But Oaxaca is crying.”

The heavy evening rain that followed the massacre accentuated the atmosphere of mourning and resignation – but also rage and resilience – the following day. Rarely have I seen so many stores closed in Oaxaca City, even in 2006, when a similar pattern of protest and repression led to the six-month popular takeover of Oaxaca City to protest the state government’s repression of striking education workers. Some residents feared a federal police assault on the central city plaza (Zócalo), where education workers and supporters continued to hold an occupation (plantón). The movement’s main demand: the end of the neoliberal “education reform” enacted in 2012, which eliminated the constitutional guarantee of a free public education established in Mexico after the Mexican revolution 100 years ago.

Other residents took the day to march in protest against the federal police’s armed intervention. The blunt rhythm of their chant— “Assassins! Assassins! Assassins!”— ricocheted off the stone buildings of the central plaza, a UNESCO World Heritage site. Though education workers and supporters staged a large mega-march a week earlier, before the killings, this march sent an even stronger message to the state and federal governments. Protesters continued to stream into the plaza more than two hours after the first ones had arrived. Some education workers I spoke with had left the rural district of Putla at 3 A.M. to arrive in Oaxaca City in time for the protest. Others had slept overnight in the Zocálo.

In indigenous towns elsewhere in the state, families held public funerals for the slain.

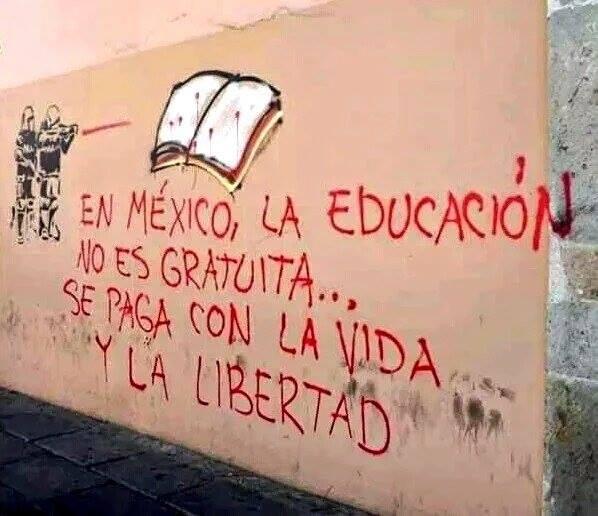

"In Mexico education is not free. It is paid for with life and with freedom.”

Much like in 2006, the street art that blossomed on the streets of downtown Oaxaca City after the killings captured essential truths in a moment when official voices offered orchestrated untruths. The prior day, the Mexican Secretary of the Interior affirmed that the Mexican federal police were unarmed, even as photos circulated on social media showing them with high-caliber firearms, and witnesses saw bodies fall.

On social media, at least one federal police officer postured and bragged, sending images of bloodied Oaxacan bodies as trophies and threats.

Oaxaca has proven to be one of the last strongholds in resisting a global wave of similar education reforms in the last two decades, and its state-wide local union (Sección 22) is one of the most radical in the hemisphere. It successfully resisted the reform until last year, when a sophisticated and extensive mass media campaign demonized Oaxacan teachers and smoothed the way for the state government to suddenly impose many of the reform’s measures. The social movement that has emerged against the reforms, which are sponsored by a host of national and international corporations and financial institutions, rejects the policy as a back-door way to discipline and shrink the educational labor force, require local residents to pay for education, sell access to schools to foreign corporations, and absolve the federal government of responsibility for educating its citizens.

As in 2006, few predicted the nature and breadth of the popular groundswell that has risen to support education workers as they contended with violent repression. In 2006, then-governor Ulises Ruíz broke with the routinized pattern of mobilization and negotiation, in which Sección 22 presented its annual demands in February, and then launched an occupation of the central plaza in May as it negotiated with the state government. Ruíz Ortiz refused to negotiate, and attempted to evict education workers from their customary plantón. Social and indigenous organizations, along with Oaxaca City residents and education workers, helped form the backbone of the 2006 movement as they created the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca (APPO).

In 2016, the support looks different, yet recent events make evident its breadth. Oaxaca City is no longer the main site of contention. While Sección 22 has called for strategic road blockades in Oaxaca, the union’s state assembly itself never actually called for the takeover of the main highway to Mexico City at Nochixtlán, as Luis Hernández Navarro has noted. Parents and supporters in this highly indigenous (Ñuu Savi) town helped lead the way, and they are now demanding explanations for why the federal police chose to attempt an eviction on the town’s market day, when thousands of regional residents visit the town to buy and sell. As the police attacked on the June 19, officers peppered their tear gas volleys with racial slurs.

In nearby Chiapas, another majority-indigenous state, education workers have also stood up to the reform, and teachers reported that police called them “damn monkey-eaters.” Since the killings, Mexican supporters have staged marches everywhere from Cancún to conservative Chichuahua and Monterrey, and numerous cities across the globe have been witness to local actions. The United Nations is investigating the attack in Nochixtlan for excessive use of state force and in denying medical care to civilian victims, an international war crime. Many in the area report that the main hospital attended only wounded police. One Oaxaca City doctor told me doctors who came to help were retained at regional police checkpoints.

The repressive strategies of the state and federal government resemble those in 2006, but also differ in significant ways. In 2006, residents prevented the police from controlling the city for six months until the federal police arrived. In 2016, state and federal governments sent in the federal police after only one month. As Scott Campbell has noted, no single day in 2006 was as fatal as June 19, 2016. In the evening after the murders, as movement supporters built barricades around the Zocálo in light of what seemed to be an eminent attack, federal police helicopters swept slow and low over downtown streets, intimidating locals with the thunder of their engines. Earlier that day, helicopters had veered, extra-low, into the sea of protesters, repelling them with the sheer force of the air currents produced by rotor blades, much like the water cannons used against them in 2006. In blockades in the Isthmus region, education workers reported spy drones circling their encampment.

Yet other control strategies, like the terror inspired by selective killings, closely resemble those of 2006. On Sunday, a community journalist and anarchist was killed in Huajapan (near Nochixtlán), where he long supported the radio station Tu un Ñuu Savi (Voice of the People of the Rain), which played a critical role in spreading information on the 19th. In Oaxaca City, armed porros (hired thugs) roamed Radio Universidad in the nights after the 19th, and movement supporters guarding the radio de-escalated confrontations. As in 2006, the state government has successfully blocked the frequency of Radio Plantón, the union’s radio station, leaving Radio Universidad as the sole radio voice of the movement in the capital city. In Nochixtlán, the mayor-elect has affirmed that locals live in a kind of psychosis. Many injured by firearms are scared to seek medical help for fear of being captured by police. Likewise, in 2006, some teachers buried documents that identified them as teachers for fear of being persecuted.

The local media has also contributed to the fear by inspiring public anxiety about the movement itself. The PRI-supporting El Imparcial has followed the governor’s lead in distinguishing “good” protesters from “bad” ones as a divide-and-control strategy. According to the media, the downtown barricades the night of the 19th were populated by “common criminals” and people dedicated to “assault,” the newspaper claimed, and locals were terrified of being out at night. Yet a friend and I spent several hours walking around the perimeter of the Zocálothat evening and into the early morning of June 20, at one point stopping for tacos at a taqueria open less than 100 feet from a barricade. I spent time at the downtown plantón after midnight several nights last week, and I have observed that a significant percentage of those occupying the plaza at night are women.

The militancy of the regional roadblocks, many of which are supported by local municipal authorities, is particularly threatening to the government, as it indicates the depth of popular antagonism. Government officials and cooperative media have tried to claim the roadblocks reflect the union’s lack of concern for Oaxacans in general, since they are causing a dangerous scarcity of goods in Oaxaca. Yet my conversations with locals in both central Oaxaca City and in outlying areas over the last week reveal the exaggerations of government claims, at least as they pertain to the central valley of the state. Sección 22 has repeatedly focused on blocking corporate goods, like Coca-Cola, at roadblocks, and Coca-Cola distribution was limited last week. While price upticks for products like chicken and avocado from central Mexico undoubtedly affected many, my conversations with working-class locals have also revealed a pride in the self-sufficiency of the state in the face of crisis. Shelves in small stores and food markets were full, they reiterated, and several joked about the presumed inability of Oaxacans—many of whom come from rural, farming families who have endured centuries of racial discrimination —to take care of themselves. In 2006, many striking teachers survived because family members sent food from their farms; in some cases, they lent land to striking education workers, who themselves took to cultivating crops.

“Urgent! Urgent! Evaluate the President!”

I spent much of June conducting interviews with working-class residents of Oaxaca City’s outer neighborhoods, and the slogan above — a chant often heard at education workers’ marches— nicely captures the double standards that outrage many of these residents feel.

Why do teachers face stringent standardized evaluation exams, but not politicians like the President, long ridiculed for being unable to list three books that have influenced him? How can the government arrest and detain union leaders for corruption and other charges, when major political bosses – including Ulises Ruíz – commit mass fraud and violence, but are politically rewarded rather than punished?

Many Oaxacans have invested time and money in their local schools. Many helped to physically build them. On weekends, through collective work arrangements called tequio, they help maintain and beautify schools. They have done so even though the federal constitution guaranteed free public education. While the June 19th killings reiterated for many Oaxacans the Mexican government’s willingness to write off their lives and labor, they also helped bring together a wide range of popular and indigenous struggles in the state, particularly around mining and energy projects. Until double standards about government treatment of elites and everyday citizens, including union members, are addressed, life in Oaxaca after the June 19 massacre will likely continue to be defined by the wide-ranging movement against neoliberal education reform.

Eric Larson is assistant professor of Crime and Justice Studies at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. He can be contacted at elarson@umassd.edu.