This article originally appeared on Lobelog.

On September 19 and 20, world leaders will convene at the UN General Assembly for the first-ever Summit for Refugees and Migration. Although focusing primarily on the refugee crisis in Syria, the Summit provides an opportunity to reflect on a humanitarian crisis that persists much closer to our borders in southern Mexico.

In the summer of 2014, 70,000 Central American children arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border, seeking refuge from the life-threatening conditions they faced in their home countries of Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. In response, the U.S. government devised the Southern Border Plan, or Plan Frontera Sur, to stop migrants and asylum-seekers in Mexico before they reach the United States. Since July 2014, the United States has provided the Mexican government with additional funding to increase migration authority staff, as well as new detection technologies and detention centers.

By prioritizing border security over human security, the U.S. and Mexico have both defied international law according to which a person cannot be sent back to a country where they face threats to their life and person. Not until January 2016 did the U.S. government announce any specific refugee program to allow Central American child migrants to remain in the country. In late July 2016, President Obama finally announced an expansion of the program. At the same time, the Obama administration has led raids specifically to deport Central Americans. Between January 2014 and October 2015, as many as 83 U.S. deportees were murdered upon their return to El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.

The U.S. media has provided little coverage of Central Americans who apply for refugee status in Mexico—and is a topic that deserves discussion at the Summit. In 2015, the Instituto Nacional de Migración (INM) apprehended almost 36,000 people from Central America. But according to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), 3,423 people, mostly from El Salvador and Honduras, have applied for refugee status in Mexico. The director of the UNHCR office in Tapachula, Chiapas, Perrine Leclerc, said in a meeting in July 2016 that in the first half of 2016, 80% of asylum applications for Central Americans settling in Mexico were accepted. In 2014 and 2015, just 21% of asylum applications from Central Americans seeking asylum in Mexico were accepted. According to numerous studies, the INM often fails to inform people they apprehend about their rights to apply for asylum.

In addition to the INM reneging on its duty to inform migrants of their rights to apply for asylum, capacity for intake and processing of asylum applications is disturbingly inadequate. Along the 500-mile border, there are just two UNHCR offices—in Tapachula and Tenosique, Tabasco—while the Mexican refugee agency, COMAR, has only three offices throughout all of Mexico. The numerous migrant shelters in Chiapas, Tabasco, and Oaxaca struggle with overcrowding and poor conditions. This stands in stark contrast to the at least $79 million supplemental aid package that the U.S. government sent to Mexico in 2015 to securitize the border, in addition to the yearly budget for the U.S.-Mexico bilateral security initiative, Plan Mérida, which has included over $2.6 billion in U.S. funding since 2008.

On the Ground in Mexico

The results of Plan Frontera Sur have been called “vertical.” Perversely, the borders themselves remain fairly easy to cross, but further north migration checkpoints and detention centers begin to crop up with more frequency. In July, I traveled to Tapachula and surrounding areas in Chiapas to observe its impact on the thousands of Central Americans with persuasive claims to refugee status in Mexico and the United States.

There are two border crossings directly outside of Tapachula—in Talísman and at the Rio Suchiate. Both are notoriously easy to cross. The “securitization” here is much less obvious than a wall or the presence of migration officials at the border itself.

At the Talísman border crossing, dozens gather around the INM building each day, their heavy backpacks covered in dust from long journeys. Here, one can simply walk into Mexico. At the Rio Suchiate, boats travel back and forth between Mexico and Guatemala with seeming tranquility. For these migrants, the overt, violent threats had come before and would likely come again in the form of the bureaucratic games these migrants face while attempting to apply for asylum.

At least 10 security checkpoints have been set up on the most traditional migrant route along the Pacific Coast of Mexico—between Huixtla and Tuxtla Gutierrez, the capital of Chiapas. One of these checkpoints in Chiapas, near the small city of Comitán, is an imposing concrete behemoth and giant empty parking lot, equipped with INM officers and soldiers holding kill-grade weapons. Built in 2015, the checkpoint has over 100 staff members, according to a report by the Washington Office on Latin America.

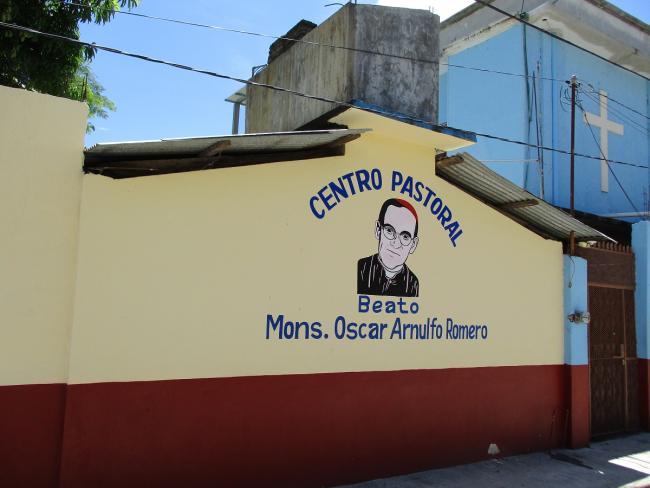

Because of surveillance like the new detention center in Comítan, more people have begun taking a route through central Chiapas. Since the implementation of Plan Frontera Sur, the Catholic Church has opened two new shelters in Central Chiapas, outside of the traditional shelter network along the Pacific trail.

Civil Society Steps In

As government policies are counterproductive to migrants’ safety, local people and civil society have stepped in to help. The Catholic Church has opened a new shelter in Comalapa, a border crossing that has become more popular in the last two years. Churchwomen run a comedor (dining room) where they serve meals to migrants and others who settle temporarily while waiting to hear the results of their asylum applications—a process that can officially take up to 90 days but often takes longer in practice. However, migrant shelters usually allow people to stay only up to 72 hours before they continue on their journey, due to extreme space shortage and overcrowding.

Some shelters specialize in people awaiting the results of their asylum applications, but they are severely under-resourced. Some migrants, like a family we met in Comalapa, have to somehow scrounge together funds to rent an apartment while they wait, though they are not legally allowed to work during this process. Others have been forced to wait out the process in detention centers such as Siglo XXI, located in Tapachula itself, with a capacity of 1000 people, according to Salva Lacruz, who works at Centro de Derechos Humanos Fray Matías de Córdóva. The facility is often overcrowded, however, with up to 15 people sharing a single cell, he said. Legally, people can only be held in a detention center for up to 72 hours, but in practice, this is often not the case.

For people traveling through central Chiapas, it is even harder to receive refugee status in Mexico than in Tapachula or Tenosique. In Comalapa, I met a young family—Pablo, his wife Daniela, who was pregnant, and Pablito (names changed)—who had fled El Salvador after gangs killed Pablo’s brother and threatened to kill Pablo next. Pablo broke down in tears as he told his story. “I worry most about my parents,” Pablo said, “I worry about their safety every day.” Despite his credible claims for asylum, he will have difficulty winning his case.

If a person wants to apply for refugee status in a place without UNHCR or COMAR offices, they must apply directly with the INM, where the likelihood of receiving refugee status is much lower. There are just two UNHCR offices and COMAR offices in the state of Chiapas. Plus, the bureaucracy and difficulty of the application process have led some to abandon their applications entirely. “COMAR is doing a very deficient job,” said Laura Díaz de León, the director of the Human Rights and Migration program at the Instituto para la Seguridad y la Democracia (Security and Democracy Institute), a Mexico City-based NGO. According to Díaz, many applicants begin the asylum process but never hear from COMAR again. She added that such bureaucratic deficiencies have not been adequately monitored or investigated.

I spoke to one man in Tapachula, who preferred that his name not be used, whose story illustrated these deficiencies. He had initially travelled from Honduras to Mexico City, where he’d worked under the table and applied for asylum status with the COMAR office in Mexico City. However, in Mexico City, he had been told that because he entered the country in Tapachula, he would need to apply in the state of Chiapas. In Chiapas, he was told that because he worked in Mexico City, he would need to apply there. Now he was stuck in limbo in Tapachula, not knowing whether his application was being processed, as his money dwindled away. He’d originally gone to Mexico City to be further from the gang threats he was facing.

Central Americans awaiting the status of their claims are forced to work odd jobs under the table, everything from packing fruit and laying bricks to making scarves and ironing. They frequently face abuse and xenophobia from their employers. One young pregnant girl from Honduras told me that she’d worked 20-hour days in a fruit factory from 5 AM to midnight, six days a week, for 100 pesos (about $8) a day. She told me that many others at the shelter where she was staying resorted to begging.

The Central Americans fleeing their homes due to real threats of violence deserve international protection. The misguided, insufficient responses by both the U.S. and Mexican governments constitute human rights abuses. When world leaders come together to talk about migration next week at the UN summit, they must push Washington and Mexico City to provide the resources and the attention that these refugees need.

Laura Weiss is the web editor for NACLA and a master's student at NYU's Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies.