This article is the first in a series of NACLA reflections on Fidel Castro’s passing—and his significance for Cuba, Latin America, and beyond.

Yesterday morning, Cubans woke up to the news that the 90-year old leader Fidel Castro had died. It was an event much expected and anticipated, given Fidel’s ailing health and advanced years, but it still took Cubans and the world by surprise. It was a particularly hard blow coming so soon on the heels of the election of Donald Trump to the U.S. presidency. In some ways these events represent the waning of one era marked by wealth redistribution downwards, international solidarity with oppressed peoples, and pro-poor governance to another that signals an intensification of free market capitalism, wealth redistribution upwards, and a rhetoric of borders and walls that unleashes rampant xenophobia and racism.

The American mainstream media and hardliner Cubans in Miami have long presented the Cuban socialist system as entirely dependent on the iron fist leadership of Fidel Castro, with his much awaited death leading to celebrations in the streets and the downfall of the system. Yet this view is wrong on several counts. Fidel managed a transition in leadership to his brother Raúl ten years ago, when his health started to decline. In practical terms, Fidel’s death presents little to no challenge to the everyday functioning of the Cuban government. And when Raúl retires in two years, there will be a transition in leadership to Vice-President Miguel Díaz-Canel, ensuring a continuity with the Castro brothers’ policies and programs.

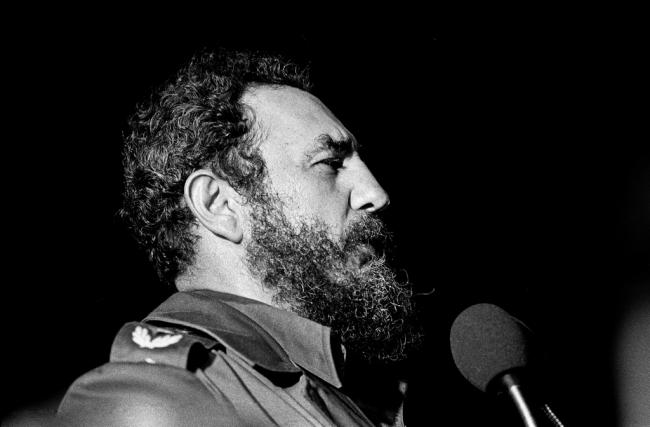

While there have been mixed reactions in Cuba to Fidel’s death, there are no large celebrations on the streets. This is only partly due to fear of reprisal: for many Cubans, particularly of an older generation, Fidel still represents the idealism and hopes of an earlier generation that they could create an independent and equitable socialist system on an island under the yoke of the United States. For all of Fidel’s errors and flaws in leadership, and they were many, he pursued this dream single-mindedly for many decades. He survived numerous assassination attempts, outlived many U.S. presidents, and always sought to extend the outreach of the Cuban revolution abroad through solidarity with liberation struggles and medical and educational assistance, which will be some of his greatest legacies as leader of Cuba.

There will be no quick transition to a market society as a result of Fidel’s death. While the media has often presented Cubans as clamouring for market freedoms denied to them, the past few decades of experimentation with market reforms have resulted in widely increasing racial and economic divisions in Cuban society. Although the Cuban socialist system became dysfunctional after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Cuban leadership has had to tread carefully in their market reforms to preserve the most important and cherished aspects of Cuban socialism, including the health care and education systems. Cubans could see the vast inequalities that opened up in Russia and Eastern Europe after the collapse of communism, and that was not a model they wanted to emulate.

Fidel was beloved by many for his charismatic style of leadership that kept him close to the people and to their concerns. A Cuban friend of mine, now in her mid-40s, recalled the day that Fidel came to her elementary school. There was no formal visit announced and the children didn’t even realize he was coming until they saw him enter the schoolyard with a few of his guards. He sat with the children and asked them about their day, and what they were learning about in school. For my friend, that day forever marked her view of the president as someone who cared about the people and wanted to get their input.

At other times, he could be seen as a micro-manager who demanded people’s attention and allegiance. On the evening of September 11, 2001, Fidel reflected on the events of that day in a nationally broadcast address from a new elementary school that he was inaugurating. In front of a group of ten and eleven-year-olds, Fidel expressed sympathy for the American people, offered the resources of the country for treatment of the victims, and urged caution on the part of the American government. In the middle of a statement about why the United States should not be carried away in a fit of rage and start dropping bombs on innocent people, he paused to reprimand a young schoolgirl sitting at her desk: “Put down that pencil. Don’t doodle. Try to pay attention while I’m talking.”

Cuban musicians and artists tended to refrain from references to Fidel in their artistic productions partly in a bid to avoid censorship. They sometimes used veiled references to Fidel, such as Daniel Díaz Torres’ 1991 film Alicia en el pueblo de Maravillas (Alice in Wondertown). Alicia is a satirical comedy about a drama coach who goes to a small town called Maravillas for her obligatory year of community service. The director for the corrupt and mismanaged Sanatorium for Active Therapy and Neurology (SATAN) in Maravillas was rumored to be a caricature of Fidel, and the film was withdrawn from theatres after four days. In 1989, an exhibition at the Castillo de la Real Fuerza was closed when it was found to include a portrait of Fidel Castro in drag with large breasts and leading a political rally. This period was one of provocative political art and confrontations with the art establishment, but in the wake of censorship, artists again moved to safer topics.

Despite the lack of tolerance for anti-establishment art in Cuba, Fidel showed himself willing to engage with new cultural genres like rap music during the 1990s. At a National Championship baseball game in 1999, when the Cuban national team played the Baltimore Orioles, instead of the obligatory salsa song, before the game started they chose to play a song by the Cuban rap group Doble Filo. The whole stadium rapped along with the group, including Fidel Castro himself. American actor Danny Hoch, who was present at the game, called Fidel “the first world leader to embrace hip-hop.”

A much maligned figure seen by some as the Castro dictator, and loved by many others who referred to him endearingly as Fidel, he is remarkable for his very survival in a world that sought to eliminate young black, indigenous, and third world revolutionaries. Lumumba, Che, Sukarno, Malcolm, Allende, Anna Mae Aquash, Fred Hampton—all were gunned down before they could bring to fruition the visions of equality and justice to which they dedicated their lives. By sheer luck or ingenuity, Fidel and the Cuban revolution survived to provide an alternative model of a socialist society. In the current dystopian Trump era, it will be important to keep alive the memory of what Fidel Castro and others of his generation stood for.

Sujatha Fernandes is Professor of Political Economy and Sociology at the University of Sydney. She is the author of Cuba Represent! Cuban Arts, State Power, and the Making of New Revolutionary Cultures.