For Sandra Rodríguez Nieto, and in memory of the late Mike O’Connor

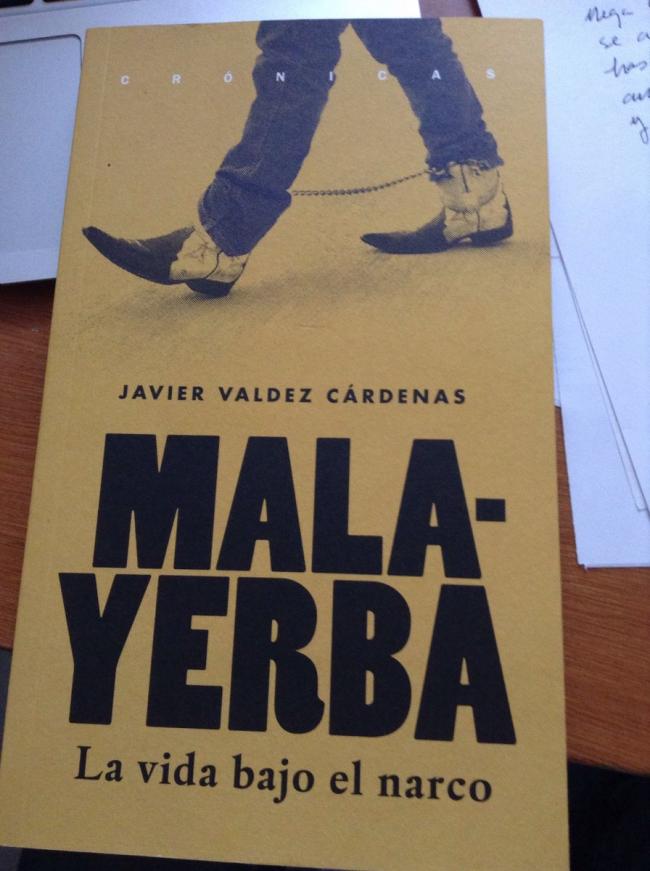

Mexican journalist Javier Valdez, who was slain on May 15, published one of his last “Malayerba” (Bad Weed) stories in the last week of March. The Malayerba was a weekly column appearing on Mondays in the newspaper RíoDoce. It is a type of crónica, a dramatic story in less than 900 words about “life under the narco.” Valdez once said, “all the stories are real.” There are hundreds of them. In “They are going to kill you,” Valdez told the story of a newspaper journalist whose family and friends warned him that his outspoken, critical coverage of corruption would get him killed.

Valdez’s fictional journalist character did not heed the concerns, “using his keyboard, his words, to pelt corrupt politicians for conspiring with criminals, police at the mafia’s command.” The journalist character’s murder – “point blank so as not to miss” – by gunmen came three hours after he posted about a corrupt lawmaker on social media.

Two months later, on May 15, Valdez’s Malayerba came balefully true. In the bleached-out midday sun of a hot street in Culiacán, the capital of the state of Sinaloa, the recently turned 50-year-old journalist met an untimely end.

That day, at least two gunmen ambushed Valdez near his newspaper offices in downtown Culiacán. They forced him out of his car at gunpoint, and then, in what appears coordinated action, fired thirteen shots into him. One of the hitmen fled in the reporter’s car, but quickly abandoned it, taking Valdez’s computer and phone.

Since his assassination, reporters, some close colleagues, and even the Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression for the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, have blamed organized crime. More specifically, these reports attribute his killing to the bloody dispute between dueling factions within the Sinaloa Cartel. The cartel, headless in the absence of El Chapo, who awaits trial in New York, is mired in a conflict within its younger generation, which is likely responsible for a leap in the state’s homicide rate. The dispute worsened last summer with the kidnapping and subsequent release of El Chapo’s sons in Puerta Vallarta, perhaps by Dámaso López, El Chapo's renegade lieutenant. This act, along with the Mexican Army's capturing of Sinaloa Cartel hit men has put the Cartel’s factions on the defensive, and the state on high alert.

Was Valdez a victim of this dispute? It seems beyond question that an interview he published on February 20 in RíoDoce with an emissary from Dámaso López, resulted in ire from other sects of the cartel, and brought him threats, including gunmen touring newspaper stands buying up all copies of the newspaper. In the interview, López denied kidnapping El Chapo’s sons and said he was a friend of El Mayo Zambada, the de facto new leader of the Sinaloa Cartel. But was the interview enough to kill him? Did El Chapo’s sons, newly resurgent and powerful with López’s recent capture in Mexico City and imprisonment in Ciudad Juárez, need to put themselves under the spotlight with Valdez’s murder? His friend, Froylán Enciso, writer, analyst, and historian of the political economy of drugs in Sinaloa, wrote after the assassination that he could not understand why Chapo’s sons would kill Valdez after López’s imprisonment.

The narco thesis behind Valdez’s murder makes a great deal of narrative sense. It makes sense in the absence of forensic evidence and the obvious incapacity of the Mexican state to investigate murder cases (the country has an impunity rate of about 98 percent) and the understandable desire for closure and certainty. But the explanation of Valdez’s murder at the hands of a psychopathic, power hungry narco needs to be placed alongside the statements Valdez made time and time again about where he thought threats came from: politicians or public officials in collusion with, and protecting the narco— but not the narcos per se. Indeed, when journalist John Gibler, perhaps one of the most astute of Mexico’s foreign correspondents, traveled to Culiacán in early February for Al-Jazeera, Valdez did not report that he feared the narco, but rather said, “That’s why it is ‘organized crime,’ because they have people inside the Mexican state—people inside the governmental apparatus—working for them, because the police form a part of the criminal structure, because they have an army of hired killers, because they have financial operatives and business people—whom no one bothers, by the way— also involved.” In this sense, his Malyerba “They are going to kill you,” crónica identified in story form what Valdez said endangered journalists: the politicians and public officials who facilitate organized crime.

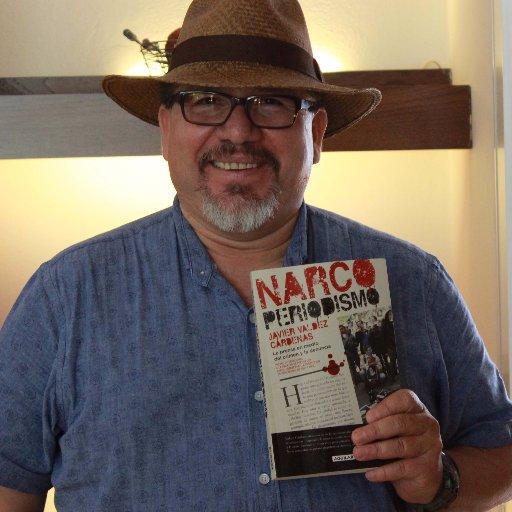

The Risks of Narcoperiodismo

Eight months before his assassination, in October 2016, Valdez had just published the eighth of his nine books, Narcoperiodismo. The journalist and author gave an interview to newspaper Reforma about the months he spent traveling throughout Mexico, interviewing reporters, compiling the threats they faced, and what they did to survive. After all that traveling, the death toll of Mexican journalists mounting all the while he wrote his book, he told reporter Andro Aguilar: “I fear the government more than I fear the narco.” He went on: “There’s drug trafficking because there is no government … the principal problem with practicing journalism is la autoridad [translated as “the government”]. The political class is the child of drug trafficking. Intolerant, dangerous, powerful, colluding with organized crime, every type of criminal.”

Valdez explained that threats to journalists came from reporting on how politicians and officials corrupted themselves with money from the narco. In “They are going to kill you,” Valdez’s fictional journalist would not shut up about a scandal concerning a corrupt legislator, describing the forces imperiling the journalist: “politicians for conspiring with criminals, police at the mafia’s command;” the “shit-covered governor,” and “the mayor flush with funds.” His fictional journalist’s subjects mirrored Valdez’s real life reporting: “the business dealings of the powerful.”

Narcoperiodismo is Valdez’s clear statement— in book form— of the threats that politicians and public officials pose for Mexico’s journalists. It is worth quoting at length:

"There are more and more disappeared, tortured, and murdered journalists in Mexico. Aware of the problem that drug trafficking has angrily chewed across every border, we can think that it’s only the cartels’ emissaries who give the order to execute, kidnap, electro-shock so that they don’t write again for the newspaper that is making things uncomfortable, disturbing and meddling in things. But no. It is not only the narcos who disappear and murder photographers, editors, journalists. Politicians, police, organized crime also have a task of exterminating, so they collude with officers, prosecutors, public officials, and members of the military. The great sin, the unpardonable crime, is to write about the painful events that shake our country. To denounce the mismanagement of the treasury, the alliance between narcos and the government, to photograph the exact moment of repression, to give voice to victims, critics, and the damaged. The great mistake is to live in Mexico and to be a journalist."

Even closer to his murder than the publication of Narcoperiodismo, and according to reports from journalist protection specialists who spoke to Valdez, he did not feel immediately at risk. But he did seem to be increasingly worried about articles RíoDoce had published since January “about links between local politicians and drug traffickers,” he told the Committee to Protect Journalist’s Carlos Lauría. “This is something different,” he told CPJ. He refused to go public with the specific threats, publishing instead “They want to kill you” which nobody— either then or now— links to an imminent danger.

Its author now dead, “They are going to kill you” leaves its reader with an eerie premonition about what happened to Valdez a few weeks later in mid-May. If he was in danger, it seems that he used the threat as the source for another chilling Malayerba. And even though he went to Mexico City the week before his murder in what seems to be a plan to escape, he then returned to Culiacán. His co-editor at RíoDoce, Ismael Bojórquez, told a reporter for Ciro Gómez Leyva’s news program that there was no money to go elsewhere he had to keep working.

“They are going to kill you” is told in the style typical to the Malayerba, a style all Valdez ’s own: in the third person, short, rhythmic sentences, crystalline images, no way to identify his subjects, not even the journalist who was being threatened. Gabriela Polit, the University of Texas academic who first introduced Valdez to an English-speaking readership, wrote after his murder that Valdez had created his own narrative form “combining Poe’s ideas about storytelling with poetry.”

As with every Malayerba, Valdez published the link to “They are going to kill you” on his Facebook page, as did the fictional gunshot journalist in the story. In the comments section, one friend recommended Valdez take care, repeating the same concern the fictional Malayerba journalist failed to heed. Valdez responded with customary poise— or heedlessness— about the closeness of death for a journalist in Mexico: “Thanks, dearest. I don’t know how to do it, really. I have lost all the maps and escape routes. In this country you have to fight with death like you are in the bullring… and involuntarily.” Three days before, on 24 March 2017, a gunman had assassinated investigative journalist Miroslava Breach in Chihuahua, a case that infuriated Valdez who, like Breach, was also a correspondent for national newspaper La Jornada. Several weeks later, assassins’ bullets befell Valdez. As he predicted in his Facebook comment, there was no escape for the journalist when confronted by the two gunmen who forced him out of his car to assassinate him.

“They are going to kill you” is not the only Malayerba in which Valdez described the threat to journalists coming from politicians. In “La Costeña,” published in RíoDoce on 24 October 2016, about three weeks after his Reforma interview, Valdez wrote about a young, recently graduated female journalist filled with idealism, “writing with dignity in indelible ink.” She published a story that grabbed headlines in the region and beyond.

"One day a case came into her hands. The governor’s corruption. Money in all of his pockets, pedaling influence, taking advantage of public services for personal benefit, or for the benefit of a few. All in private.

That night she went home to celebrate her success with her parents. Instead, when she opened the door to their house she found them dead, lying on the ground. Their murders forced her into exile, “hidden. The same fate as those whom he sent to kill.”

Valdez’s life ended like many of the people - including the reporters - who populate the Malayerba: at the barrel of a gun, without explanation.

A More Nuanced Understanding of Valdez's Life Work - and Death

The Malayerba, and his other work, including plenty of interviews and presentations at book fairs, shows that Valdez was not a drug war journalist. It’s a significant misconception.

Valdez did not report on cartels and their inner workings— he left that task, as he intimated in Narcoperiodismo, to Ismael Bojórquez another of RíoDoce’s cofounders. In that respect Valdez was unlike the drug war reporting practiced by Bojórquez and journalists like Anabel Hernández, herself the subject of serious and repeated threats.

Valdez was always interested in the social effects of living with drug traffickers and their politician and public official facilitators—“life under the narco,” he called it. And yet in every interview, journalists seemingly unfamiliar with his output always asked if he wrote about the narco. Five days before his murder, SinEmbargo published an interview with Valdez on the publication of Malayerba’s second edition, asking him, “Are you a person who specializes in the narco?” He gave more or less the same answer he gave everybody who asked this thoughtless question:

“Look, I think I’m an expert in people ... specialized in telling the story of people who are in the narco. Yes, I do have information from the grassroots about the bosses, but my work has been more about people who have had to suffer the narco.”

The SinEmbargo interview is one of Valdez’s last interviews about the Malayerba. He clarified what “narco” meant to him, it wasn’t a person. Narco is something that exists inside all Mexicans.

“Its presence within us has spread and now we are not just talking about Sinaloa and the North, but the whole country. Our narco is the one in the mirror staring back at us, recognizing us. We suffer and we enjoy being the narco.”

For Valdez, Malayerba was a series of stories with impossible endings. First published in 2010 with a prologue by Carlos Monsivaís, it was his favorite of his nine books. Readers agree: Editorial Jus, its publisher has just published a second edition, and Valdez had been presenting it on a book tour. Since May 15 and its author’s murder, Malayerba is also the book of what it is like to die under the narco: without quarter.

Valdez was a journalist of considerable stature and importance, and part of the proof was his immense, lyrical and empirical output. RíoDoce— the newspaper he cofounded with Ismael Bojórquez and Alejandro Sicairos—provided stable, gainful employment to its journalists and production team. Valdez trained a generation of provincial Mexican journalists in a country dominated by a media elite in Mexico City. He mastered and innovated within the crónica, a narrative form of journalism popularized by Gabriel García Márquez, among others. Valdez authored many books – one of which, Levantones, about the human costs of disappearances, has just appeared in a sparkling English translation and magisterial introduction to Sinaloa by Everard Meade as The Taken. He gave interviews to all comers, and guided foreign journalists around his state, even though he also satirized them in Malayerba (see, “Todos los güeros son gringos,” or “All the Light-Skinned Are Gringos." As a foreign correspondent for Agence France Presse, he is also one of the few journalists attached to an international media organization killed in the context of Mexico’s drug war.

Given his accomplishments as a writer and human being— he leaves behind a wife, and two children —Valdez warrants the same nuanced, complex approach to his murder that he provided others in his detailed, thoughtful narratives. And, along with the scores of journalists murdered in contemporary Mexico he also deserves justice.

Whether the Mexican justice system can deliver a complex interpretation of his death based on evidence, including his journalism, and according to international human rights norms, is everybody's hope and nobody’s expectation: since 2000, more than 100 journalists have been killed in Mexico, with most cases mired in the morass that is impunity in drug war Mexico. The Mexican state’s capacity in the murder of journalists, human rights defenders, migrants and citizens, is to reproduce— systematically — its widespread incapacity to prosecute cases.

Malayerba’s author knew the immense dimensions of impunity in Mexico: he worked with mothers of the disappeared. He saw the problem of impunity with clarity – in Huérfanos del Narco he wrote about children with parents killed in the drug war. He refused to back down or off from threats that paralyzed other journalists. But one problem with the murder that Valdez himself foretold is that few seem to have been reading his Malayerba to understand how trapped he was. And that terrible awareness, for somebody like myself who translated some but not enough of the stories into English, is a hit of very bad weed indeed.

Patrick Timmons is an independent human rights investigator, journalist, and sometime community college history professor. He edits a blog, the Mexican Journalism Translation Project, which showcases English translations of exceptional articles by Mexican and Central American journalists, including a fraction of the Malayerba. Timmons published, “Trump’s Wall at Nixon’s Border,” in the Spring issue of NACLA: Report on the Americas. Last September for NACLA’s website he published “Every Journalist Mourns a Journalist,” about threatened Veracruz reporter, Noé Zavaleta.