Last week, the Bolivian government launched a highly contested community consultation process on its plan to build a highway through the Isiboro-Sécure Indigenous Territory and National Park (TIPNIS). Affected communities responded with a creative range of tactics—some in support and others in resistance—attesting to the deep divisions the process has created.

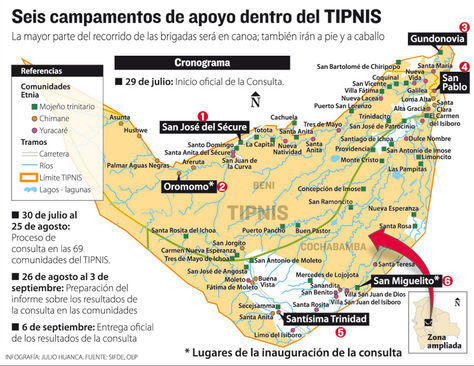

Over the next four weeks, 16 government-sponsored brigades are scheduled to travel to remote regions of the vast reserve by canoe, foot, and horseback to carry out the consulta, spending 1-2 days in each of 69 communities. Each brigade will include two public officials, a logistical coordinator, and three indigenous facilitators. Decisions will be made by the local assembly in each community in accordance with its traditions and customs. If all goes according to plan (which is unlikely), the results will be reported by September 6.

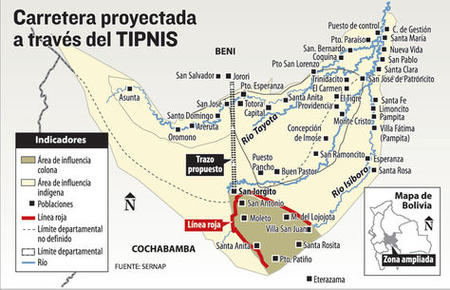

The consulta was inaugurated in Oromomo, a community located in the northwestern section of the park close to the route of the proposed road (see maps). Last March, Oromomo was the first TIPNIS community to benefit from the government's gift of outboard motors, delivered personally by President Evo Morales. Following this visit, a pro-government faction took over the contested Sécure Subcentral, the indigenous governing authority in which Oromomo participates, which had previously opposed construction of the road.

Not surprisingly, the consulta in Oromomo concluded with a decision to endorse the road. But the community added its own twist, conditioning its support on an economic compensation package including health services, education, and community development. “The road brings development, and only if it’s built will we be able to get the basic services we need,” said Jhonny Ervi, an indigenous Oromomo authority.

By adding this proviso, the community sought to exploit the linkage between the proposed highway and development that has been a central theme of the Morales government’s pro-road campaign. At the Oromomo ceremony inaugurating the consulta, Environmental Minister Felipe Quispe presented the community’s upcoming decision on the road as a choice between remaining in poverty or advancing through education and development. Indigenous authorities who signed an agreement with the government last month say they were promised development and services in exchange for supporting the road.

Oromomo also rejected the continued designation of the reserve as a protected “untouchable” zone, a legal status secured by the first TIPNIS march last October. A successful ecotourism program (generating $20,000 per month for five TIPNIS communities, including Oromomo) was terminated by the Morales government last year, based on the government's interpretation that the law precludes even sustainable development initiatives managed by park’s indigenous inhabitants.

Oromomo also rejected the continued designation of the reserve as a protected “untouchable” zone, a legal status secured by the first TIPNIS march last October. A successful ecotourism program (generating $20,000 per month for five TIPNIS communities, including Oromomo) was terminated by the Morales government last year, based on the government's interpretation that the law precludes even sustainable development initiatives managed by park’s indigenous inhabitants.

As Amnesty International has noted, the wording of the consulta reinforces this prejudicial view, by asking communities to decide “whether the TIPNIS should be a protected zone or not, in order to make possible the development of activities of the Moxeño-Trinitario, Chimane, and Yuracaré indigenous people, as well as the construction of the Villa Tunari-San Ignacio de Moxos highway.“ AI has broadly criticized the consulta for “link(ing) the development of the communities—including in health, education, and the use of natural resources for subsistence—to the construction of the road,” despite the fact that “the rights of indigenous people, such as health and education, are an obligation of the state, independent of any highway construction.”

The second community to implement the consulta, San Miguelito, rejected the reserve’s “untouchable” status but also decided to oppose the road. The decision surprised many, since this community, while affiliated with the TIPNIS Subcentral which has opposed the road, is located in the southern zone of the park adjacent to communities that are increasingly linked to the coca economy, who support it. “We know that the road won’t benefit us, and therefore we have opposed it,” said mayor César Davalos, criticizing government officials for failing to fully disclose the road’s potential environmental impacts.

To date, a total of eight consulted communities (mostly clustered in the park’s southern zone) have officially decided to support the road while two have opposed it. Another 18 have announced plans to actively resist both the road and the consulta. The resistance is centered around Gundonovia, gateway to the park in the northeast, where communities have blockaded the rivers with barbed wire to impede the entry of additional brigades. At least six port communities are currently blockaded, along with the San Pablo airport.

Distant from the proposed road, these communities perceive the risks associated with its construction as far outweighing any potential development or service benefits. As Fernando Vargas, president of the TIPNIS Subcentral, explains: “We are defending our territories so we don’t disappear. We’re fighting for our lives. We don’t want to depose President Evo; we only demand respect for our rights and territories.”

TIPNIS leaders and allied organizations are also pursuing three legal remedies in different courts to block implementation of the consulta (one claim has been rejected, but will be appealed). They argue that the Morales government has failed to comply with the Constitutional Tribunal’s order issued last June (and recently reaffirmed), requiring consensus to be achieved with affected groups on the consulta process and content so that it can proceed with mutual respect. According to the government, communities that dissent from (or resist) the consulta process or its results must abide by the views of the majority under the Bolivian constitution. Indigenous leaders say the consulta law requires the process to be conducted in accordance with the traditions of affected communities, who operate by consensus.

TIPNIS leaders and allied organizations are also pursuing three legal remedies in different courts to block implementation of the consulta (one claim has been rejected, but will be appealed). They argue that the Morales government has failed to comply with the Constitutional Tribunal’s order issued last June (and recently reaffirmed), requiring consensus to be achieved with affected groups on the consulta process and content so that it can proceed with mutual respect. According to the government, communities that dissent from (or resist) the consulta process or its results must abide by the views of the majority under the Bolivian constitution. Indigenous leaders say the consulta law requires the process to be conducted in accordance with the traditions of affected communities, who operate by consensus.

As tensions mount, all sides will take advantage of a brief respite as the consulta is suspended for Bolivian Independence Day (August 6). For an update on the consulta status by community, see Fundación Tierra’s interactive map.

Emily Achtenberg is an urban planner and the author of NACLA’s weekly blog Rebel Currents, covering Latin American social movements and progressive governments (nacla.org/blog/rebel-currents).