This piece appeared in the Spring 2024 issue of NACLA's quarterly print magazine, the NACLA Report. Subscribe in print today!

Leer este artículo en español.

A few days before Javier Milei took office as president of Argentina, threats began flowing into line 144, a helpline exclusively intended to respond to reports of gender-based violence. In addition to the calls, bomb threats targeting the headquarters of the Ministry of Women, Gender, and Diversity forced the premises where the helpline operates to be evacuated for a few hours. It was a planned operation to intimidate the dozens of phone operators who have worked in the department since it was created 10 years ago.

Why did multiple people call to insult and threaten the operators of a helpline that provides psychological and legal assistance to victims of gender-based violence? What battles are they waging or think they are waging with this kind of psychological micro-war? What do these events tell us about the connections between elections, political emotions, and cultural changes? How do right-wing organizations seduce, convince, and move their followers? And what political and epistemological challenges do we face, and will we face, as a result of the growth of the far right in Latin America and beyond?

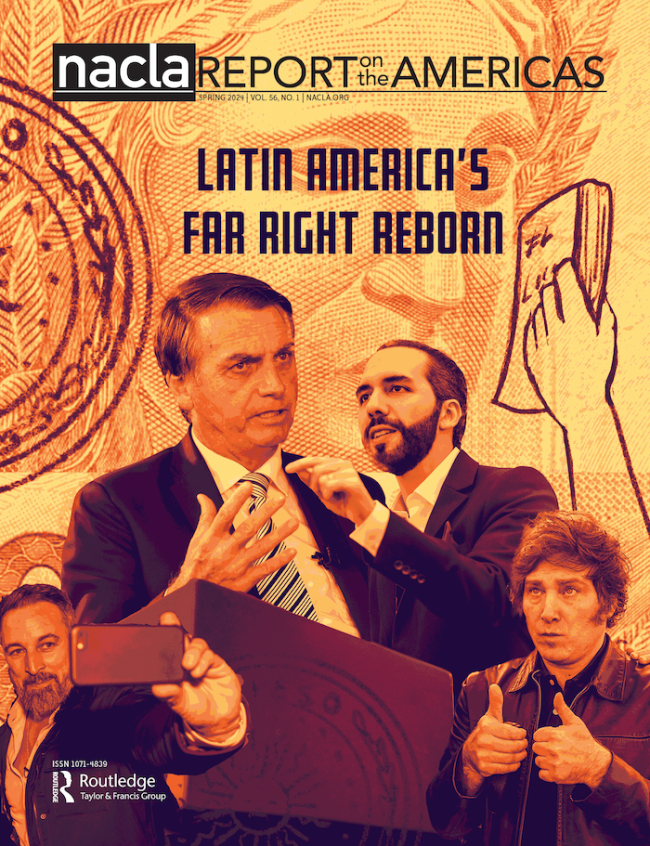

This issue of the NACLA Report presents readers with the perspectives of more than a dozen experts from different countries. These authors reflect on the ideological specificities of the far-right phenomenon and its links with historically rooted social and political processes, such as the nature of democratic restoration, the socioeconomic impacts of neoliberal economics, and the geopolitical challenges posed by “progressivism” and Bolivarianism. With these articles, we hope to contribute to understandings of specific aspects of these right-wing processes and the similarities—and connections—that exist beyond national borders.

This issue includes articles focusing on different countries—Argentina, Brazil, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Paraguay, and Uruguay—and on different political and intellectual leaders of the far right, such as Javier Milei, Nayib Bukele, Jair Bolsonaro, Mario Vargas Llosa, Payo Cubas, Luis Abinader, and Guido Manini Ríos, among others. Authors take interest in what happens in parliaments and the decisions made by political institutions. But in these pages readers will also enter less formal areas of politics, where the far right seems to be in its element. In this way, this issue allows us to peer into the impact of figures like the Brazilian YouTube guru Olavo de Carvalho, the publishing networks buttressing a far-right common sense among Argentine youth, the networks of think tanks and soft power deployed by the Fundación Internacional para la Libertad (FIL), as well as the forms of intimidation and physical violence that Black Dominican women face today.

Climate Change, Political Change

Much of the planet has entered a phase in which, due to climate change, phenomena that were once considered far-fetched now seem increasingly probable. On Earth today, unforeseen and extreme temperature variations, changing rainfall patterns provoking droughts and floods, and intense winds are the order of the day. Politics seems to have followed the climate in this sense, as we now frequently face political episodes that were unthinkable a decade ago. The novel contours of these processes have not always been correctly interpreted by political analysts, who have wavered on what to call this latest right-wing tide.

A retired Army captain who for more than 25 years vegetated as a backbench lawmaker in the so-called “lower clergy” of Brazil’s Congress became president of his country in 2018. A doctrinaire economist, more famous for his dramatic TV appearances than for politics, defeated the Peronist candidate in Argentina’s 2023 elections. Chile went from massively repudiating the long legacy of General Augusto Pinochet’s neoliberalism at the end of 2019 to giving majority support at the polls to José Antonio Kast’s ultra-conservative party in a second constitutional process four years later. A mob stormed the U.S. Capitol at the beginning of 2021, certain they were stopping a conspiracy of Democrats, pedophiles, and woke people.

Over the last decade, we have seen an accelerated shift in the electorates of European and Latin American countries toward the right and far right. This process has been expressed in a strengthening of parliamentary blocs associated with conservative values and, in some cases, electoral victories allowing leaders of these movements to reach presidential offices. In Latin America, this shift has gone hand in hand with re-readings in two particular areas. First, dictatorial pasts and their human rights violations have been the object of renewed revisionism and at times denialism on the part of far-right forces—a reaction to the advances of legal and historical investigations, as well as memory and educational policies related to these issues. Second, offensives against what the far-right calls “gender ideology” have skyrocketed, expressed in the repudiation of the legalization of abortion and in bitter anti-feminist sentiments.

In some countries, far-right forces have challenged the promotion of new rights such as marriage equality, adoption by queer couples, or the legalization of marijuana, as well as developments on the issue of sexual education in primary schools. This pushback has gone hand in hand with the growing weight of emotion in politics, over and above argument, polemics, or reason. The digitalization of life has contributed to the expression of emotions like hatred, indignation, and affinity having more and more weight in comparison to the pretense of representation and argumentation. These factors all combine to weaken our understandings of the storm through which was are passing.

New Definitions, Transnational Links, and Forms of Violence

Among other takeaways, readers will find within this issue, we would like to highlight three themes. First is the question of what to call these political forces, whether “far right 2.0,” “neopatriots,” “neoliberal authoritarianism,” “illiberals,” or something else. Second is the question of whether the rise of the far right is an international phenomenon within which we can identify connections, alliances, and mutual support between these figures, or whether we need to concentrate on the national scale to understand (and combat!) these threats. Third is the question of how to understand the link between these new political forces and the various forms of symbolic, physical, and institutional violence they wield.

On the first question, this NACLA Report reflects the multiplicity of terms with which political analysts attempt to make sense of the current far-right phenomenon. Is it nothing more than a repeat of fascism? The authors do not come to a consensus on the defining characteristics of these new right wings or what to call them. Lorena Soler writes of the “new business-led right,” José Antonio Sanahuja and Camilo López Burian of “neopatriots,” and Steven Forti of “extreme rights 2.0” and “alt-right.” Beyond their particularities, these new far rights seem to share signs of an identity that links them to the old radical right to varying degrees, without alternative proposals for the future. Are we facing, then, an essentially reactive phenomenon, channeling indignation and rising emotional intensity?

Other articles invite us to think about the appropriate scale of analysis for studying right-wing social and political actors who interact within neoliberal, anti-populist networks. Pieces by María Julia Giménez and Stéphane Boisard take up this issue in relation to the Fundación Internacional para la Libertad, while Ezequiel Saferstein and Analía Goldentul consider it in spaces where cultural products and figures make their mark. As Sanahuja and López Burian remind us, although these far rights employ certain vocabularies, communication styles, and historical narratives, we cannot adequately understand their rise if we look only within this sphere. And although these forces bear family resemblances and are part of a common epoch, we can more accurately approach and understand their specific nuances and challenges within each country’s context. Some articles focus on identifying the new right’s deep roots within national processes. Rodrigo Patto Sá Motta explores the role of anticommunist imaginaries in structuring political polarization in 20th- and 21st-century Brazil, while pieces by Oldilon Caldeira Neto on Brazil and by Magdalena Broquetas and Gerardo Caetano on Uruguay address the open wounds and legacies of the dictatorships of the 1970s and 1980s.

Other articles focus on novel practices of violence, both physical and discursive. Lucrecia Molinari writes about the brutal security policies implemented in El Salvador, and Amarilys Estrella sheds light on the harassment waged against racialized groups in the supposedly plural society of the Dominican Republic. In addition to the intensification of physical violence—let us not forget the far-right attempted assassination of Argentina’s Vice President Cristina Fernández in 2022—the articles in this issue also highlight the growth of increasingly brutal forms of interpersonal interaction and political conversation. The pieces by Patto Sá Motta on anti-PTism in Brazil and by Saferstein and Goldentul on Argentine readers of the far right show the astonishing ease with which the limits of what can be said and how have shifted when it comes to coexistence: intolerance, racism, and aggression have increasingly morphed into what passes as honesty and authenticity.

In his essay On the Concept of History, written at the beginning of World War II as Nazi barbarism was on the horizon, the German philosopher Walter Benjamin postulated: “[E]ven the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins. And this enemy has not ceased to be victorious.” We hope this issue contributes to a better understanding of the capabilities, expectations, and modus operandi of the enemy.

■

We thank NACLA for the invitation to put together this issue, as well as Heather Gies, who as managing editor of the NACLA Report was largely responsible for the editorial process and an advocate for the readers of this issue. We also express our appreciation for the authors, who accepted our invitation to write for a broad audience, and in many cases accomplished that task in the middle of their summer vacations.

Translated from Spanish by NACLA. Explore the table of contents and the rest of this issue.

Ernesto Bohoslavsky is a historian and professor at the Universidad Nacional de General Sarmiento in Argentina. His research is focused mainly on anticommunism during the Cold War in South America.

Magdalena Broquetas is a historian and professor at the Universidad de la República in Uruguay. She has researched right-wing and extreme right-wing organizations in Uruguay between the 1950s and 1970s.