The following article was written in conjunction with the Spring 2012 NACLA Report on the Americas, “Central America: Legacies of War.” The issue is now available here.

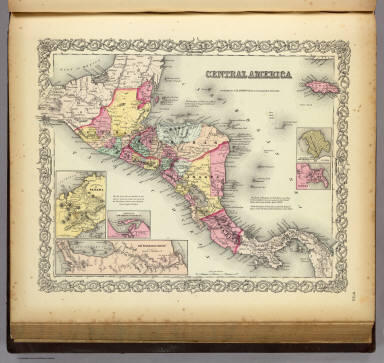

Even to many who paid attention to the rest of Latin America, Central America was terra incognita into the 1970s. As the Sandinista revolution heated up in Nicaragua, and the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) launched offensives in El Salvador, I learned some of the names of people and movements, but I didn't really know where all these countries were.

I distinctly remember one night in the late 1970s when I pulled out the atlas and located them in the very small area that they occupied on the continental map. This was the beginning of my intense engagement with Central America, and there was much more to learn. As U.S. president Ronald Reagan said in December 1982, shortly after his first official trip to Latin America, "You'd be surprised. They're all individual countries."1

Geography, climate, and history combined to give each country its distinctive characteristics: Nicaragua, then run by the Somoza dynasty after 20 years of occupation by the U.S. marines; El Salvador, then ruled by the coffee oligarchy; Guatemala, with indigenous groups in the highlands speaking 22 different languages; Honduras, whose plantations made it the classic banana republic, but gave it a strong union tradition among the banana workers; and relatively isolated Costa Rica, which took the luxury of abolishing its army and created a social democratic welfare state unequalled in the hemisphere before the Cuban revolution.

According to an aphorism attributed, perhaps apocryphally, to Ambrose Bierce, war is God's way of teaching Americans geography. My experience in Central America was marked by the wars of the 1980s: the Contra War in Nicaragua, where I assisted the resettlement of refugees in the war-torn Estelí region, and the civil war in El Salvador, where I worked for the non-governmental Human Rights Commission and worked with and researched the popular education movement in FMLN-controlled zones—eventually writing a book about it. I have never been closer to war than I was in Nicaragua and El Salvador, and those experiences became the prism through which I have viewed U.S. military intervention ever since.

The experience was intense. Combatants acted with heroism and suffered grievous losses. Others, like the human rights defenders and popular teachers I worked with in El Salvador, found that their work was affected in every dimension by the war. Friends died. I experienced the repression myself when I was detained for two days by the Salvadoran army. All of these groups heroically resisted imperialism, but in the end the war meant tragedy and waste on all sides. I saw at first hand the destructiveness wreaked by U.S. intervention in support of the Contras and the Salvadoran government, and the futility of trying to impose a U.S. vision of democracy that, in oligarchically ruled societies, meant little in the context of massive social and economic inequality.

Central America has moved on from wartime, with mixed results. While all welcomed peace, few feel they have achieved what they fought for. The heirs of the Sandinistas in power defend the poor and repudiate neoliberalism, but make shady deals with their former enemies. The FMLN has elected president Mauricio Funes, but his range of maneuver is highly limited by international economic pressures. Many of the poor people who fought for liberation in the 1980s, and their children, find that their best hope is migration to the country that was responsible for so much destruction in their own countries.

Meanwhile I have watched U.S. intervention move on to new parts of the world—Iraq, Bosnia, Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iran, Libya, and the hundreds of bases circling the globe. God is still teaching us geography.

John L. Hammond teaches sociology at the City University of New York and is a member of NACLA's editorial committee. He is the author of Fighting to Learn: Popular Education and Guerrilla War in El Salvador (Rutgers University Press, 1998).

1. Lou Cannon, “Latin Trip an Eye-Opener For Reagan,” The Washington Post, December 6, 1982, A1.