This piece appeared in the Fall 2023 issue of NACLA's quarterly print magazine, the NACLA Report. Subscribe in print today!

October 25, 2023 marks the 40th anniversary of Operation Urgent Fury, the U.S. invasion of Grenada that launched a Cold War military intervention in the island nation. October 9, 2023 similarly marks the 70th anniversary of the British invasion of British Guiana (now Guyana) to depose the democratically elected multiracial and leftist government of the People’s Progressive Party—the first government to become a casualty of the Cold War in the Western Hemisphere. In one invasion, the United States rained down missiles and bombs on an independent nation that was imploding; in the other, British troops walked eerily down the deserted streets of their colony. Both events would have longstanding consequences in those countries and across the region.

Decades have passed and much has changed since the invasions of Grenada and Guyana highlighted the Cold War-era use of ideas about “creeping communism” to justify military force and intervention. Now, however, the Caribbean is living a new era of imperial meddling. Today, foreign governments for the most part no longer use military might to direct the internal affairs of Caribbean nations—though in the case of places like Haiti, this remains the modus operandi of the United States and United Nations. Instead, the leading foreign threat stems from transnational capitalists that are once again seeking fortunes in the region, promoting extractivist activities while often influencing local politics in their favor.

Postcolonial governments, for their part, have not been innocent bystanders. Many are deeply implicated in, and initiators of, new forms of oppression, land-grabbing, and resource extraction. Standing against these neoliberal forces are everyday people and leaders who resist dispossession and erasure, push back against capitalist greed, and reach for an alternative vision of the Caribbean. As in the past, the region continues to reshape and rebuild itself in the afterlife of empire. And although the term “afterlife” gestures to the continuing impact of a bygone imperialism, the evolutions and latest iterations of imperial power in the region mean that for many—especially the peoples living in places that remain territories, departments, or outright colonies—this afterlife of empire feels very much like the old empire.

■

This issue of the NACLA Report departs from this understanding of empire in the Caribbean. In response to the theme, Jamaican filmmaker and activist Esther Figueroa asked us an important question: “Is empire the most important thing about us?” Our answer: it certainly is not. Her query is an important one. In fact, many of the articles in this issue remind us that the Caribbean is not simply empire’s playground, but rather a space where people have created and continue to create powerful, beautiful, vibrant, and at times devastating histories and presents. These articles demonstrate that today, those with broader social justice visions continue to fight for decolonized futures and to defend and protect the Earth. They organize for better lives and more equitable economies, for health care and land rights, for democracy and justice. They create art, community, and people’s congresses. They believe in the commons—for all of us.

The realities facing the Caribbean today evoke the major dilemmas of our time: the climate crisis, extractive capitalism, displacement, migration, and struggles for decolonization, reparations, and self-determination. The articles gathered in this issue seek to address those big questions head-on. They consider how capitalist extraction through mining, drilling, and debt production are shaping island and mainland futures, how climate change is making and remaking the natural environment and people's lives, and how resistance to these and other harmful dynamics in the region is ever in the foreground.

As 2023 marks the 200th anniversary of the Monroe Doctrine—the U.S. foreign policy position used to justify imperialism in the hemisphere—a first pair of articles chart histories of military intervention with far-reaching importance. Shalini Puri’s haunting piece on the stakes of our memories and understandings of both the 1979 Grenada Revolution and the 1983 U.S. invasion asks us to go beyond simple Cold War narratives. Reconsidering how we remember and centering the perspective of Grenadians tells a regional story of solidarity, political tensions and fissures, and imagined futures—with reverberations far beyond the Caribbean. In another tale of imperial punishment, Jemima Pierre details how decades of foreign meddling in Haiti are now poised to shape the United States’ global policy towards so-called fragile states. U.S. foreign policy initiatives that undermine and infringe on regional sovereignty remain a present-day threat.

Turning to the other side of the island of Hispaniola, Simón Rodríguez examines the Dominican Republic’s long history of anti-Haitian and anti-Black legislation. Considering the plight of Haitian migrants and Dominicans of Haitian descent alongside Israel’s treatment of Palestinians and the export of that country’s technologies of racial oppression, Rodríguez offers a provocative analysis of what he calls the Dominican apartheid project. Of course, anti-Black immigration policy toward Caribbean peoples stretches outside the region. Across the Atlantic, Peter Timothy explores the history and continuing impact of the United Kingdom’s racial discrimination against the Windrush generation. Seventy-five years after the 1948 voyage of the HMT Empire Windrush that transported the first groups of West Indian migrants recruited to England in an effort to address Europe’s post-war labor shortages, Britain’s postcolonial debts remain palpable.

Continuing to grapple with the meanings and memories of the Commonwealth, Traci-Ann Wint reflects on Jamaica’s current form of “flag independence.” As the island prepares to join some of its neighbors in breaking with the monarchy, Wint asks what full independence could mean for the country given the neocolonial dynamics of U.S. hegemony in the region and Jamaica’s reliance on tourism as an economic engine.

Melanie White takes us to Nicaragua, where Daniel Ortega, one of the leaders of the 1979 leftist Sandinista Revolution, has morphed into an autocratic ruler who has harshly repressed uprisings across the country. Largely absent from the national discourse on the crackdown, White outlines, are the racialized, sexualized, and gender-based violences against Black and Indigenous feminist and LGBT organizers who advance anti-colonial pathways for the Miskitu Coast, the strip of territory along the Caribbean Sea previously colonized by the British and currently under Nicaraguan and Honduran rule.

A next set of articles delve into issues of extractivism, the climate crisis, and struggles to defend life, land, and livelihood. From Suriname, Richard Price covers the precarious struggle of Maroon and Indigenous peoples against the postcolonial state and multinational corporations, highlighting the devastating impacts of corruption, drug trafficking, logging, and mining. Turning to a new frontier of offshore drilling in Guyana, Janette Bulkan, Roshini Kempadoo, and D. Alissa Trotz tackle the history of empire and extraction, today’s oil economy, and the importance of women’s community organizing in imagining alternatives to the world of fossil fuels. In a companion piece in the Arts and Reviews section, Kempadoo continues this exploration through her exhibition Like Gold Dust, evoking connections between the state of Texas and Guyana, and reminding us of the key role of art in resistance and alternative building.

Roberto Kus, Levi Gahman, Adaeze Greenidge, and Filiberto Penados pick up these threads in southern Belize. In a photo essay, they explore Maya efforts to defend the commons against climate devastation and the imperial and postcolonial moves to encroach on their land and autonomy through extraction and neoliberal “development.”

Across the Caribbean, the plantation has long been a mechanism of extractive exploitation. Kevin Edmond’s piece offers a prescient warning about the potential pitfalls of cannabis legalization, particularly in Jamaica. He argues that wide-scale legalization that fails to account for the communities that have traditionally cultivated marijuana—often facing criminal penalties—will reinscribe the plantation logics that have created and deepened racism and inequality in the region. Then, as longstanding agricultural challenges meld with new climate threats, Francis Russell and Carlos E. Ramos-Scharrón analyze the current conditions of Puerto Rico’s coffee growers, offering a potential way forward through collective organizing and governance in the archipelago’s long-marginalized coffee sector.

An essay on the urgency of addressing fiscal precarity makes clear the high stakes of the region’s ever-enmeshed nexus of sovereign debt and climate change. Ketaki Zodgekar, Avery Raines, Fayola Jacobs, and Patrick Bigger highlight how climate chaos, fueled by the profit-driven whims of Global North countries, is having out-sized consequences for Caribbean nations, which struggle to finance recovery under predatory and extractive debt regimes. Their piece underlines that climate and economic justice must go hand in hand, and reparations must be on the agenda.

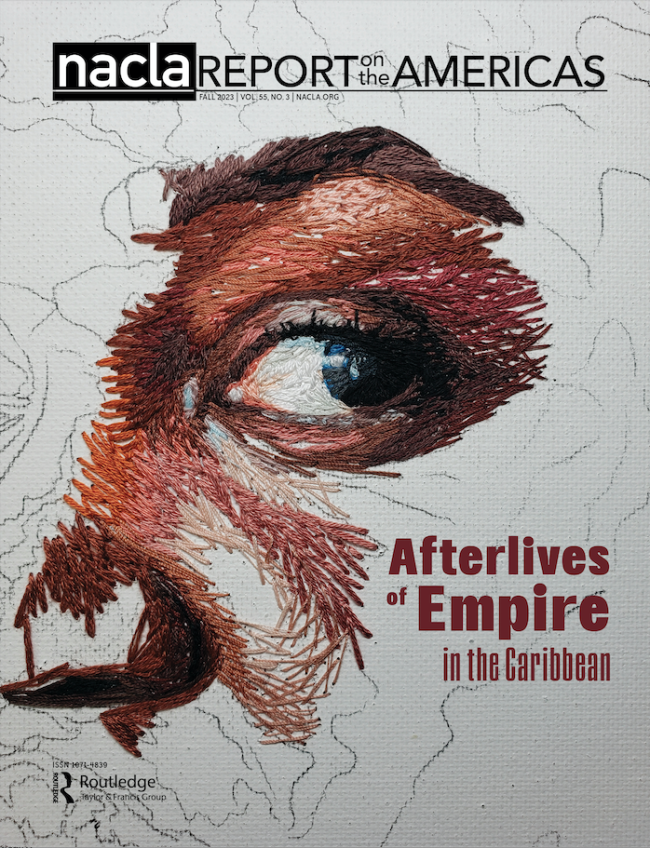

Finally, as the storms and resistance rage on, the poetry of Mónica A. Jiménez reminds us that there have always been sounds, whispers, and songs “outside the cacophony of empire.” Similarly, Trinidadian artist Nneka Jones’s embroidery artwork, which graces the cover of this issue, prompts us to weave, design, and bring new possibilities into being.

■

In the 2014 essay “Why Caribbean History Matters,” historian Lillian Guerra provocatively writes that Caribbean history “addresses the most fundamental questions of who we are, what we believe, and how we got that way.” In short, the history of the Caribbean is the history of the world—of capitalism, Indigenous dispossession and genocide, enslavement, indenture, and migration. It is also the history of resistance, decolonization, imagination, and world-making. These have been and continue to be the big questions of our collective existence. The authors in this issue take up Guerra’s call to arms and directly engage the histories and afterlives of empire as they are lived in the Caribbean today. In doing so, they not only advance our regional understandings, but also ask us to imagine and remake our world anew.

Explore the table of contents and the rest of this issue.

Nicole Burrowes is an assistant professor of History at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, and a community organizer. Her current book project is titled Seeds of Solidarity: African-Indian Relations and the 1935 Labor Rebellions in British Guiana.

Mónica A. Jiménez is a poet, historian, and assistant professor of African and African Diaspora Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. She is author of the forthcoming book Making Never-Never Land: Race and Law in the Creation of Puerto Rico.

Cover artwork by Nneka Jones.