This piece appeared in the Fall 2022 issue of NACLA's quarterly print magazine, the NACLA Report. Subscribe in print today!

The first time I visited Berlin was in1987, two years before Berliners tore down their infamous wall, the symbol of the geopolitical chasm between socialism and capitalism built in 1961 by the Soviet Union. I wasn’t surprised at the time to find massive housing complexes in East Berlin neighborhoods like Hellersdorf and Marzhan that were very similar to the ones still filling up the skyline of Havana’s eastern municipality: Habana del Este.

Two decades later, I found myself drowning in a strange sense of familiarity when, walking through Manhattan on a hot summer night, I was suddenly hit with the characteristic smell of downtown Havana: an indescribable mix of vapors from sewer and gas pipes flowing with the exudations of old walls and rusty neo-baroque ironwork. Another summer, in Spain, I was again under the impression of traveling back to my hometown. As I walked along the sea promenade immediately after arriving at Cádiz’s train station in the southwestern part of the country, I felt like I didn’t know where I was: Cádiz? Havana?

What happened to me on all three occasions along my global journey as a Cuban migrant weren’t inexplicable acts of magic or soothing poetics. Behind my experiences stood the most intimate tale of Havana, a history that can be read in the city’s crumbling buildings and cracked sidewalks and that enthralls the senses on every corner of the city where I grew up.

Havana’s urban history is like the history of all Caribbean cities, where architectural trends and building materials have always come from remote metropolises. In general, Caribbean architectural layout follows European models, while Indigenous structures are almost nonexistent today, and relegated to rural spaces. In Caribbean cities, there are no vestiges of Indigenous urban architecture, like Mexico City’s Templo Mayor de Tenochtitlán or Peru’s Andean city of the Incas, Machu Picchu. None of our cities possess those famous ruins that—despite being heavily damaged or hidden under layers of stone and cement by the modernizing obsessions of European colonizers and post-colonial elites—have managed to survive destruction and endure as evidence of powerful Indigenous civilizations in the Americas.

In contrast, our Caribbean cities reveal an unrelenting urbanistic coloniality. The Hispanic domination over Cuba from 1492 to 1898 explains my sensorial disarray in Cádiz. And, in New York, what my sense of smell detected was the sweat of steel, concrete, and bricks brought to Havana on ships from Philadelphia and New York; these were the materials used to build the capital’s oldest neighborhoods, such as La Habana Vieja, Centro Habana, El Cerro, and El Vedado, until the triumph of the Cuban Revolution in 1959.

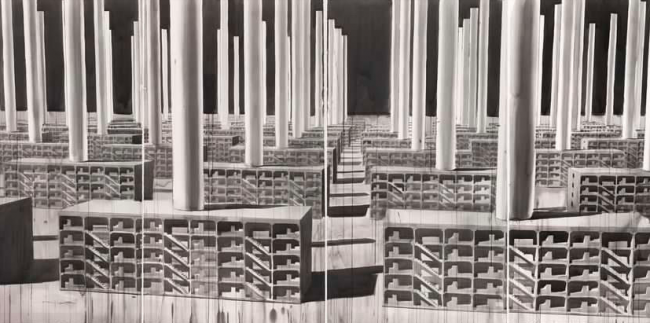

With the U.S. embargo imposed on the island in the early 1960s and the new regime’s alliance with the Soviet Union, a new era of Cuban architectural design emerged. Heavily influenced by Soviet aesthetics, the island’s archetype of socialist urbanism is Alamar. With 100 housing blocks spanning 15 kilometers (over nine miles) in the municipality of Habana del Este and a population of 90,000, Alamar is the nation’s largest housing project. Despite its spatial isolation and current state of disrepair, Alamar remains a site of creative expression and belonging. Confined to the geographic, economic, and administrative margins of current Cuban life, and surrounded by decay and frustration, in a paradoxical move, its dwellers have managed to build a main hub for underground counterculture. The awareness of their distance from Havana’s mainstream and their sense of abandonment reinforce the uniqueness and newness of Alamar’s cultural production.

Building a New Country

After Cuban leader Fidel Castro declared the socialist character of the revolution in 1961 and joined the Soviet bloc’s Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon) in 1972, almost every new construction project on the island followed the urbanistic and building designs shared by all Eastern European socialist countries. With slight variations, the same kinds of housing projects covered urban and suburban enclaves throughout the now-extinct socialist bloc, and this also became the trend for Cuban cities. I was born in Havana in the 1970s and left the city in 1995. My eyes were thus inevitably accustomed to the sight of the grey, scruffy buildings I later found in the easternmost section of Berlin, home to housing complexes built by the workers, for the workers.

Similarly, a considerable part of Cuba’s construction labor force was organized under the system of microbrigades, created by Fidel Castro in 1970 to solve the housing shortage. Microbrigades built most of Alamar.

The microbrigades were composed of workers of any trade, who for a certain time were assigned to the construction of the new buildings. Once finished, 80 percent of the apartments were distributed among the workers involved in construction, following criteria based on their merits and needs. The microbrigrades system also enabled the spirit of camaraderie that developed during the construction of the apartment blocks to persist after their inauguration, maintaining a sense of community among the first dwellers. This was particularly true in the 1970s and 1980s. But the love story started to dim in the 1990s, and the situation was significatively different.

“Alamar es el lugar,” said the writer and Alamar resident Yohamna Depestre when I met her in the early 2000s. “Alamar is the place.” I couldn’t help but ask: Whose place? A place for whom? What solidarities could be enacted in Alamar?

Depicted as a “no man’s land” by architects Joseph L. Scarpaci, Roberto Segre, and Mario Coyula in Havana: Two Faces of the Antillean Metropolis, Alamar is known for its poor building design and the lack of functional urbanistic distribution and civic centers that would encourage the integration of the complex’s youth—the children and grandchildren of the workers who decades ago built their own apartments.

Discontinuity might seem a constant feature of Alamar’s history. The first projects to develop the area were conceived in 1956, when the neighborhood’s proximity to the most coveted Havana beaches had roused the recreational and touristic industries’ interests. But the advent of the revolution halted these plans. When Alamar was finally developed in the 1970s, the same site that years before was intended to entice the appetites of the pre-revolutionary bourgeoisie became home to masses of workers from the industrial and service sectors.

Within the context of the first revolutionary decades, the project was not devoid of ideology. The newly erected uniform housing blocks, built by the workers who lived in them, would nurture the new men and women whose existence had been conjured up by Ernesto “Che” Guevara in his 1965 pamphlet “Socialism and Man in Cuba.” In a few years, the idea of Alamar went from an exclusive suburb associated with leisure and capitalistic profit to a bedroom community, the functional site where the people building a new country would retire every day to rest. Summing up its history, another Alamar resident, one of Cuba’s finest poets, Juan Carlos Flores, called this singular place “the last province of the USSR.”

Concurrent with the construction of Alamar’s housing projects, a chef-d’oeuvre of Cuban cinematography, the 1974 De cierta manera (One Way or Another), was being shot by Sara Gómez, a Black filmmaker who was the first female director in the Cuban film industry. Filmed in Miraflores, created by the Revolution to replace Las Yaguas, one of Havana’s poorest neighborhoods, De cierta manera captures the community’s transformations while narrating the tumultuous fictional love story between protagonists Mario and Yolanda.

The couple’s disagreements stem from the socioeconomic, racial, and cultural differences between the mixed-race Mario, who was born and raised in Las Yaguas, and Yolanda, a white teacher from a petty-bourgeois background who cannot understand the social dynamics of her school’s marginal enclave. She, furthermore, defends her independence as a woman, while he remains tied to traditional concepts of maleness. Mario and Yolanda’s conflicts illustrate the complexity of what happened when the Revolution suddenly brought diverse values and socioeconomic backgrounds into contact.

Their story unfolds against the backdrop of the neighborhood and its reconstruction. A constant flow of images of demolitions embodies the destruction of the old and the construction of the new. However, for the women and men living within these walls, it was not easy to break with their pasts. Guevara wrote in “Socialism and Man in Cuba” that “to build communism, a new man must be created simultaneously with the material base,” and he designed a monolithic path to achieve it. But Gómez’s Black gaze was inquisitive instead of intransigent. She couldn’t trace an inflexible line between marginality and social progress.

De cierta manera’s intricacies are fueled by the fact that, despite their differences, Mario and Yolanda were equally committed to the revolutionary process. The arguments between them weren’t expressed from opposite sides of the political spectrum. Nonetheless, their political and spatial common ground did not guarantee a complete understanding between them. The last images of the movie show them heatedly arguing in the middle of a street in Miraflores, the miserable shacks already replaced by brand-new buildings. A new material world had sprung up, but, apparently, its dwellers couldn’t change at the same pace. They were not yet the new Cubans that Guevara imagined. Their improved homes constituted indisputable proof of the socialist state’s early commitment to social equality, which would ensure—in its leaders’ view—the consolidation of a homogeneous mass of revolutionary Cubans. This was a utopian projection that didn’t include the particular worldview and sociocultural background of each individual—a vision that Gómez’s cinematic approach masterfully challenged.

The same year De cierta manera premiered, in 1977, the forerunners of the Nueva Trova movement Pablo Milanés and Silvio Rodríguez released a popular song, “Canción de la nueva escuela” (Song of the New School). As its title suggests, the song heralded the Revolution’s political orientation toward the birth of a new breed of Cubans through the construction of public and residential buildings where their ideological and ontological education as revolutionaries would be accomplished. Its chorus remains in the memory of many Cubans like me, as it was regularly broadcast on radio and television and for decades chanted at political events.

Today, I wonder if this song was performed in Rodríguez’ 2010-2012 national tour, “Gira por los barrios.” On the tour, Rodríguez, who is known worldwide for his fervent and continuous endorsement of the Revolution, delivered more than 100 performances in the poorest Cuban neighborhoods. Some of the concerts in Havana’s most neglected areas, where precarity and vulnerability are widespread, were included in the 2014 documentary Canción de barrio, directed by Alejandro Rodríguez Anderson. Although the camera registered Rodríguez’s performances in a rather traditional fashion, documenting residents’ living conditions was the main focus of the movie. In its numerous interviews, generalized feelings of abandonment, frustration, and helplessness when facing the hardships of everyday life become almost tactile.

Read the rest of this article, available open access for a limited time!

Odette Casamayor-Cisneros is a Havana-born writer and scholar. An associate professor of Latin American Cultural Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, her current work examines Afro-Latin American and Afro-Latinx cultural production. Besides two academic book-projects, Casamayor is currently writing a memoir-like rendition of her Black, female, Cuban, and diasporic experience.