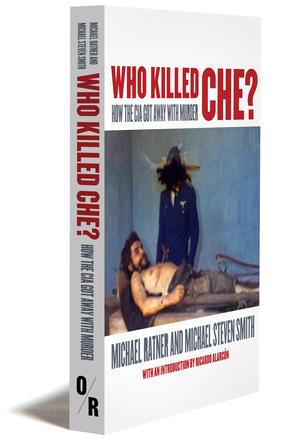

Who Killed Che? by Michael Ratner and Michael Steven Smith, OR Books, 2011, 200 pp., $16 (paperback)

In Who Killed Che? radical attorneys Michael Ratner and Michael Steven Smith lay out a forceful case indicting the U.S. government of having, in effect, killed Ernesto “Che” Guevara on October 9, 1967. They base their argument on what has been written since the event but also rely heavily on official documents secured under the Freedom of Information Act, after years of waiting. The authors establish beyond a reasonable doubt that, while the man who actually shot Guevara was Mario Terán, a Bolivian army sergeant, the order to liquidate the wounded guerrilla came from Washington. This goes against the standard story, propagated by former president Lyndon B. Johnson and other high-ranking U.S. officials, that the Bolivians ordered Che’s death.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:856:]]“The history of who is responsible for his murder has heretofore not been understood accurately, especially in America, where it is commonly believed that the Bolivian military dictatorship had him killed,” the authors write in the first paragraph. “Documents which have recently been obtained from the U.S. government lead to a different conclusion: that the U.S. government, particularly its Central Intelligence Agency, had Che murdered, having secured the participation of its Bolivian client state,” write the authors.

But this book is no dry legal brief. Nor is it just an account of Guevara’s capture and assassination. It is both an impassioned look at Che’s life and deeds and an inside glimpse into the inner workings of the CIA and U.S. foreign policy. The book is dedicated to the late Leonard Weinglass, a lawyer with extensive Cuban experience as the lead council for the Cuban Five from 2002 until his death in March 2011. Ricardo Alarcón, president of the Cuban National Assembly, penned the preface, which stresses Che’s importance today and briefly comments on the continued U.S. aggression against Cuba since the inception of the Revolution. A lengthy chronology introduces the main body of text, highlighting leading events in Che’s career as a revolutionary.

The actual text is quite short, just under 60 pages. The first section covers background material on the creation of the CIA, emphasizing the agency’s autonomy and its function as a covert military and political operator, which has allowed U.S. presidents to deny any knowledge of its actions taken to further national policy. The section “The Written Record Relating to Che’s Death” reviews the literature about Che’s Bolivian foray, underlining that most authors buy the official line that the Bolivians had sole responsibility for the killing. There follows material on the use of political assassination as a consistent instrument of U.S. policy, including congressional testimony on efforts to eliminate Che and both Fidel and Raúl Castro, among others. The authors then dissect the development of counterinsurgency strategy, beginning in the Kennedy-Johnson years, with the development of rapid-strike forces, Green Berets, and weaponry appropriate for small-scale combat against guerrilla forces.

The rest of the text is devoted directly to Che, from his early background in Argentina through his demise in Bolivia. It reads like a set of chronological snapshots. Short sections cover each particular topic or event: Guatemala, Che’s first encounter with Fidel Castro in Mexico City, the Sierra Maestra campaign. Two sections highlight Che in Africa and quote from his speeches on the need for third-world revolution and solidarity. The book, however, is not a complete biography but rather a highlight film with commentary. It shows that the CIA tracked Che even before his appearance in Cuba. Frequent quotes from both Che and the U.S. government dot the pages, as do references to the official documents in the back of the book.

The authors tackle two controversies surrounding Che, including the thorny question of Che’s attitude toward the Soviet Union, which they correctly identify as one of critical support. They also scoff at the idea that a rift developed between Che and Fidel, despite the fact that the CIA wrote about “the fall of Che Guevara” and even cited rumors that Fidel had had him killed.

“The CIA files reflect the vast rumor-mongering that spread worldwide as to whether Che and Fidel had split,” the authors write. “The truth is that there was no split. When Che joined up with Fidel and the Cubans in Mexico City in 1956, it was with the understanding that if they succeeded in Cuba, Che was free to move on.”

The last section of the book deals with Che’s Bolivian expedition, and relies heavily on Che’s diary because it is the only testimony that exists (CIA agents had lost track of Che for a considerable amount of time). This section covering Che’s assassination is the most original. It examines official accounts in detail, concluding that the U.S. government was really calling the shots and is responsible for the killing. As the authors highlight, the Bolivian government under General René Barrientos and Félix Rodríguez—a CIA operative who was present at Che’s death—lied in their reports about the killing. With the support of accompanying documents, it is clear that the United States was responsible for the killing. Two memoranda from the CIA and the Department of Defense Intelligence Agency support this thesis by saying that Che’s death vindicated the U.S. strategy of having Green Berets train Special Forces to combat guerrilla uprisings and would discourage future would-be guerrillas. This section, “Che Guevara, His Life and Death,” closes with an examination of the official death certificates and comments on Fidel’s eulogy for his dead comrade, reminding the reader of Che’s powerful and lasting legacy around the world.

By far the longest part of this work is the chapter “Documents,” which reproduces 43 secret reports, correspondence, and memoranda upon which much of the text is based. Each document is accompanied by a paragraph indicating its significance. The documents, released under the Freedom of Information Act, come from many sources, including the Lyndon Johnson Library, the CIA, the White House, and the State and Defense departments. Although some key texts are released in their entirety, many have been extensively censored to hide the names of informants and operatives. Nonetheless, the documents contain fascinating information for any reader with the patience to wade through them. As a whole they reveal that the U.S. spy system reached deeply into the highest echelons in both the United States and abroad, but also show that intelligence sources did not always provide accurate information. The several differing accounts of the capture and death of Che offer proof of this.

The authors fail to touch on one controversial question. Was Che’s campaign doomed to fail before it started? Che’s theory of foquismo—that a small band of rural guerrillas could lead an impoverished peasantry to rebellion—is attractive as a model for revolution. But were the Andes the Sierra Maestra of South America? Did Bolivia really meet the criteria at this time? Many argue that it did not, since some agrarian reform had already been implemented after the Revolution of 1952. In fact, the miners, not the peasantry, were the most radicalized sector of Bolivian society. Che himself notes more than once, in the referenced documents, that his group had no chance to recruit peasants, because they were always on the run and because their operations brought further military backlash against the agrarian communities.

“The peasant base has not yet been developed,” Che wrote in his diary in April 1967. “Of all the peasants we have seen, there is only one who appears to be cooperative, but with fear.”

On October 7, 1967, a local peasant named Pedro Peña informed the counterinsurgency forces of the group’s whereabouts. Che was captured the next afternoon after a fierce battle.

Overall, this is a very interesting book. It presents new material about Che and most particularly about the whole episode in Bolivia. It also opens small windows onto the operational workings of U.S. imperialism. This is significant. Too often this kind of examination comes either from retired operatives who have axes to grind—pro and con—or from scholars with predetermined views. Ratner and Smith give us a measured, unbiased account of the revolutionary life of one of Latin America’s most controversial figures.

Hobart Spalding is a member of the NACLA Editorial Committee and the Socialism and Democracy Cuba collective, which has published two special issues on Cuba, the latest in March 2010.