Before I ever heard "marero," a word commonly used in El Salvador and the United States to describe a gang member, I vividly remember walking home from school in the late 1980s with my older brother and cousins and witnessing the rounding up of youth in our Los Angeles neighborhood. Yellow police tape often blocked off sidewalks, and police sirens kept us up at night. Little did we know that we were witnessing the beginnings of a phenomenon that would dominate the local news for decades; that every time we Googled “El Salvador” thousands of images of children and young men with tattoos, imprisoned or lying dead on a street corner in Los Angeles or in Soyapango, El Salvador would appear. Photographs are powerful visuals that come to define a country’s past, present, and future. In the photo/essay book Unsettled: Desasosiego, photojournalist Donna De Cesare depicts Guatemalan and Salvadoran people’s past and present as one with a very saddening and depressing dimension, and with a bleak vision of the future. The reader will not find victorious images of revolutionaries entering the town square, or occasional smiles and hugs shared between comrades, or a narrative about Central American social movements struggling to transform society. The pictures are grim, real, and above all necessary to analyze.

The author, Donna De Cesare, a photojournalist who documented the civil wars of Guatemala and El Salvador in the 1980’s, provides readers with powerful images along with her own personal narrative and analysis. Chapter One focuses on the childhood traumas produced by the civil wars of the 1980’s; Chapter Two describes the surge of Central American gangs in the barrios of Los Angeles; and Chapter Three brings readers back to El Salvador and Guatemala where gangs have proliferated. The book concludes with an epilogue that highlights the rehabilitation of a former gang member and the author’s research on prevention methods for resolving the gang crisis.

The civil war chapter takes the reader on a journey of photographs that illustrates the suffering caused by the wars in Guatemala and El Salvador, highlighting, for example, the El Mozote and Rio Sumpul massacres in El Salvador, and more specifically highlighting the wars’ traumatic impact on children. Some of the most compelling photographs in the book capture visual glimpses into the lives of terrified children, such as an image of a young Salvadoran boy who is horrified by government helicopters that have just bombed the barrio of Soyapango for three long days. Other moving images illustrate three young boys holding machine guns; the boys appear to be recruits of the Salvadoran military. In the essay that accompanies these photos, De Cesare provides an exchange between her and a military officer, whom she asks about the ages of the recruits, the officer responds with a grin, “We Salvadorans are a macho race, from the womb we are warriors ready to destroy the communist terrorist delinquents. Just look at how many youth have volunteered to clean them out.” Routinely the military would take children off buses and streets, and forcefully recruit them to join the military even though it was already mandatory for youth between the ages of 18 to 30 years old to join.

The visual journey continues into the barrios of Los Angeles, where many of the children from the war continue their lives in the darkness of the night, in which they face a different form of recruitment into street gangs. There, exploited single mothers may labor tirelessly for long hours as housekeepers or street vendors, or at other labor intensive jobs that prevent them from providing the parental attention necessary to raise children in a strange land filled with anti-gang police units, slum housing conditions, and low standards for schooling. Recruitment here is not always forceful, but may result instead from an absent father or mother, and social and economic factors that stem from poverty and institutionalized racism in the United States.

The third chapter is dedicated to gang proliferation in El Salvador and Guatemala during the postwar era, providing illustrations of gang members, deportees, and their families. In the post-war era, children and their families from the poorest sectors of society continue to rebuild their lives, but as De Cesare explains, many of them have joined gangs and face government repression and policing policies such as Plan Mano Dura in El Salvador that conducts police sweeps and incarcerates youth for mere association with a gang. The author shares a photograph of an eight-year-old gang member with tattoos who throws a MS-18 gang sign and a smile to the photographer. He is killed six months later.

The strengths of De Cesare’s work are found in both the photographic and narrative sections of the book. I appreciated De Cesare’s emphasis on repressive government-sponsored policing practices that resulted in more youth joining gangs as a means of self protection. She draws on the story of a young man, Guillermo, who is not a gang member at the time of the first police sweep in which he is captured. At the age of 15 he is arrested and incarcerated at the adult male prison known as Mariona. During his three-day ordeal in Mariona, Guillermo witnesses the gruesome killing of a friend and cannot hold back tears as he sees his friend being butchered into pieces before his eyes. The killer threatens Guillermo by stating, “Tomorrow morning it’s your turn.” Guillermo is miraculously released along with all other minors the next day. He confesses to De Cesare, “I had no choice… I joined the Mara that day.” De Cesare describes police sweeps in impoverished neighborhoods as a death sentence for youth. The sweeps, she says, have caused the proliferation of gang membership in Central America.

The author also informs the reader about existing death squads that have targeted youth throughout Central America. In El Salvador, the Sombra Negra (Black Shadow), for instance, has murdered numerous working class youth. Government authorities have investigated these killings minimally, resulting in a culture of impunity. The culture of impunity De Cesare describes has also fueled more gang violence. Gang members take matters into their own hands and perpetuate the cycle of revenge and violence.

Gang violence is indeed a serious policy issue for Central America. However, De Cesare provides evidence showing that government officials have inflated statistics about gang violence in order to justify the repressive policing practices that have endured for nearly 15 years, such as anti-youth policies spearheaded by the ARENA government of former President Francisco Flores and his Plan Mano Dura. De Cesare, as a critical photojournalist, not only makes use of photographs, but also provides other key evidence to support her arguments.

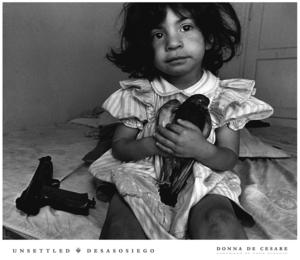

In a sea of violent imagery that is used to describe gang members and their families, De Cesare exposes the human side that is seldom found in the mass media. Gang members have multiple identities, and though the author does present them as gang members, she also describes them as fathers, sons, an uncle, a mother, a best friend who has undergone intense childhood trauma, all of whom are embattled in a crisis created by multiple actors, not just themselves. Taken together, her photographs and narrative provide a more complete and humanizing picture of children, men, and women who are rarely profiled beyond their tattoos and gang signs. De Cesare certainly makes a deliberate effort to humanize gang members, and for that reason I was surprised by the photograph chosen as the cover photo for the book itself. The photograph captures Esperanza, a three-year-old Salvadoran girl holding an injured pigeon while sitting next to a pistol. Esperanza is a child who has never operated a gun; she’s not a gang member or a soldier;. In the entire book, it’s the only photograph I find that reflects the stereotype of Salvadorans as a people who come from violence and continue to be engaged in violence. For me, the photo represents the kind of sensationalism that often dominates contemporary depictions of Salvadorans—a sensationalism that fails to see us in our full complexity and humanity.

*

In an argument that parallels the work of Elana Zilberg in her book, Space of Detention: The Making of a Transnational Gang Crisis between Los Angeles and San Salvador, De Cesare argues that violence from the civil war is a breeder for new forms of violence produced by Central American gangs. Though there is some truth to this, it is crucial to also provide a historical analysis of the origins of Central American gangs, which I believe is missing from De Cesare’s narrative. Former and rehabilitated gang member Alex Sanchez, executive director of Los Angeles based Homies Unidos provides a historical analysis regarding the origins of Central American gangs and notes that when the infamous MS gang started it was a group of rockeros (punk rockers) who did not adopt the Southern California gang member look until being incarcerated in the California prison system during brutal police programs such as Operation Hammer. The U.S. prison system was a major factor in the creation of Central American gangs and the formation of their identity. The proliferation of gangs only increased as more and more youth were incarcerated and later deported. U.S. deportation policies only fueled the cycle of violence by exporting the never-before-seen gang life to Central America.

De Cesare discusses and provides concrete examples of the impact on youth of Mano Dura policies implemented by the right-wing regimes that continued to rule both Guatemala and El Salvador in the post civil war era. However, she leaves out the uninterrupted relationship between the U.S. government and Central American governments and their collaboration on the War on Gangs. The right-wing governments developed partnerships in the 1980’s, and continued harnessing these relationships throughout the twenty-first century. Their partnerships were sustained by what they identified as a new emerging threat, targeting gang members and no longer guerrilla movements. For instance in 2005, the United States financially supported the Rapid Response Force, which was responsible for training Central American police agencies in their war on gangs. In addition, the FBI was intimately involved in the special bi-national task force whose stated goal was to train both military and police forces in Central America on anti-gang strategies. Not surprisingly, the failed U.S. strategy to eradicate gangs through aggressive policing never improved citizen security in Central America. In fact, gang membership and violence has only increased.

The author’s core argument for the proliferation of Central American gangs is focused primarily around the war-induced trauma on children. However, an important factor that could have been addressed more at length is the social inequality that remains intact in Central America. A United Nations Development Fund study on El Salvador revealed that in 1992 the richest 20% of the population received 54.5% of the national income, whereas the bottom 20% earned 3.2 %. A decade later, in 2002, the richest 20% earned 58.3% of the national income whereas the poorest 20% of the population earned 2.4%.

There are thousands of children throughout Central America who deserve a chance to live decent lives. Addressing their wartime traumas as De Cesare urges, and resolving the region’s profound class differences are both necessary steps toward solving the gang crisis of Central America.

Esther Portillo-Gonzales is the founder of Salvadorans For Civic Action, and is a board member of the Salvadoran American National Association.

Read the rest of NACLA's Winter 2013 issue: "Latino New York"