Friends of the dead gang member filed past his body, some saying a few words, others weeping. They knew it could be any of them next. There were flowers, candles in the darkness. The small family house in Soyapango, a jumble of densely packed alleys in eastern San Salvador, had been crowded since early in the day, old men, mothers, and gang members drinking coffee, smoking, waiting.

The dead youth, a member of Mara Salvatrucha, or MS-13, had been killed by rivals from the 18th Street Mara (M-18). It was 2006. We were making a film for British television and one of us was invited to the wake. At midnight, members of his clica called friends in jail, cell phone speakers held high. They sang: “The Friend I lost…” And then, with the full force of vengeance, chanted:

“Blood for blood! Blood for blood!”

“You know what to do,” came a voice across the phone.

A group left to settle scores. It didn’t matter who they killed, as long as they were from M-18. Recent recruits, kids, or ex-gang members would be easier targets. Then their friend could rest in peace. Scenes like this, repeated tens of thousands of times over two decades, are key to understanding the gang violence in which El Salvador has remained trapped, frequently giving it the highest murder rate on the planet.

Then in March 2012, with the help of independent mediators including a Catholic bishop and former defense ministry advisor, the gangs signed a truce. Almost overnight, the murder rate dropped by up to 60%. Some greeted the truce as a historic opportunity. But others were skeptical, predicting rapid breakdown, or seeing it as a maneuver by gang leaders to get better jail conditions, or evolve to international crime, drugs, and (worst of all) politics.

A year later the truce has held. Yet the whole initiative remains under a cloud of uncertainty due to the ambivalence or outright hostility of the other main players: Salvadoran lawmakers and law enforcers, the Salvadoran population, and—perhaps most important given its historical influence—the United States. This needs to change. Previous hard line policies, originally designed to fight organized crime, were based on a deep misunderstanding of the nature of the gangs and the motives of gang members, and so failed completely. A truce is the only possible path to break the cycle of revenge and allow Mara members to safely seek alternatives. Without a truce all other policies to re-habilitate or prevent violence are doomed to failure. And millions of ordinary people are condemned to live in fear.

The gang history is well known, but the defining and enduring role of inter-gang revenge is often misunderstood. The Salvadoran kids who arrived in Los Angeles in the 1980s found themselves a small minority in a gang culture with a strong racial element. “We started defending ourselves,” remembers Duke, an MS-13 founder. “We started being proud. We saw whites being proud of being white, blacks being proud of being black. Shit! Why wouldn’t we be proud of being Salvadoran?”

The El Salvador Duke remembered was in the midst of the death squad slaughter of the 1980s. “When I was seven I used to buy bread in the morning,” recalls Duke. “I used to find suckers decapitated by La Guardia—by the death squads. We saw and we learned—even if we didn’t want to—violence was in us.” The violence became part of their identity, to be proud of. MS-13, which boasted being purely Salvadoran, wanted to become the most feared gang in LA.

The 18th street gang, named after the Los Angeles street, is older. Originally Mexican, it opened its ranks to other Latino recruits. Perhaps because of their similarity, competing for the same recruits and turf, the war between the MS-13 and the M-18 became particularly bitter.

In the 1990s, U.S. authorities started mass deportations. Gang members, often with no Spanish, found themselves in an unknown country, without the protection of their companions. Yet the gang war continued. To survive, deported members of rival gangs set out to expand and recruit as fast as possible. They targeted high schools and neighborhoods, using violence and intimidation to gain control. Fear of being wiped out gave their efforts an intense urgency.

The structure of the gangs reflects their origins. They are organized around clicas, with local neighborhood leaders. Several clicas often organize together with mid-level leaders called palabreros. Above them are ranfleros and then jefes nacionales, or national leaders. It looks like a military structure. But it is not. Rather it evolved from the bottom up to allow some co-ordination between clicas. Individual clicas usually decide how to “raise funds” and distribute profits locally—rather than pass it up the structure. The national leadership, which negotiated the truce, emerged largely as a result of crowding so many clica leaders together in jail. But they do not exercise military style command and control. Even decisions in the jail appear to be by consensus.

This almost anarchic conception was there from the start. The word mara in the 1980s did not mean “gang” in Salvadoran slang. It means, “the people” in a loose sense; the crowd, movement, flow, friends who share the same culture. It had no military connotations.

The maras get most of their money from extortion of local businesses, particularly buses. In 2009 the Salvadoran transport union estimated payments of 18 million dollars. It sounds impressive, but that is 40 dollars a month per gang member, well below the minimum wage. The victims of mara extortion are themselves poor, and the extortion has been enforced by murdering bus drivers and torching buses, on one occasion with passengers still inside.

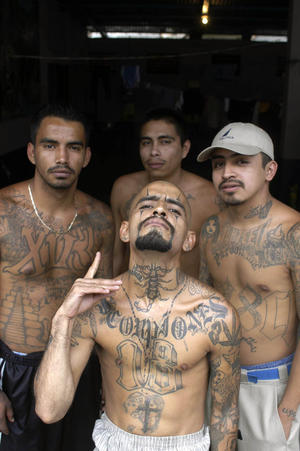

Their reliance on local extortion shows how, unlike real “transnational” organizations, the maras are rooted to their neighborhoods. If their prime interest was smuggling or participating in a clandestine war, they hardly would have been stupid enough to paint themselves from head to toe with indelible tattoos. Rather it is a cry for respect: “Take notice of us!”

This makes the Maras very different from other Latin American gangs. Brazilian gangs, for instance, were founded with military names and structures to pursue lucrative criminal activities. Wars are bad for business, so they work out deals, with each other, the police, and politicians. In El Salvador it is the other way around. The war with rivals has been ceaseless, bloody, and bitter for almost a quarter of a century.

*

Why have the gangs now signed a truce? There have been explanations, theories, and many rumors. Veteran gang members say it is because they have grown up, and as they put it, having ruined their own lives, they don’t want to ruin those of their children. “One does a lot of stupid things when young,” said Raul Solorzano, one of the jailed MS-13 leaders. “But there comes a point of maturity where you think —I’ve fucked my life!” As you watch your children grow, he said, “you begin to reflect, Damn! This one is going to turn out like me! Will these be the new generations of gang members? Or do we have to now work so that they will not commit the errors of their fathers?”

Most older gang members talk about deep war weariness, similar to that felt by veterans of the civil war 25 years ago. “We are children of the war,” said Romeo. “Look at the people today in the Legislative Assembly, or the cabinet. Those people lived violence that was also extreme, which cost El Salvador thousands of dead. Why do they now close the door on us?”

But what else do the gangs want? A second theory is that they are looking to further criminal activities by getting softer jail conditions and policing. There has been widespread worry that the government has sold out to the maras. The gang leaders insist they want nothing outside the law like an amnesty. While technically true, they clearly want mano dura—the iron fist—to end. They want an end to special rules, which exclude them from parole and place gang leaders for years on end under permanent lock down in high security prisons. At present if two or more gang members are found together, they can be arrested for “illicit association.”

Most of all, the gangs want projects to generate better social conditions and employment in the slums. The government of Mauricio Funes has gone some way towards meeting this wish list. Gang leaders have been transferred from high security jails. Police have agreed to stop the most aggressive raids in the “peace municipalities” that the gangs have declared, changing to a model more based on community policing. Prevention projects will now get 14% of the national security budget, not just 1%. But there has not been a general relaxing of police methods.

Since the truce, a series of small projects in which one of the authors has been involved have been undermined. A car bodywork and paint shop set up with four ex-gang members closed after the mechanic and painter were arrested by an army patrol for “illicit association.” A soccer pitch has been hardly used because gang members fear they will all be arrested if they form a team. One of the authors was stopped at a military roadblock giving a soccer team a ride home. As soon as the soldiers saw the tattoos, everyone, including the author, was arrested. The group, including young children, spent four hours under heavy rain at gunpoint until late evening, when government contacts secured their release.

Some clicas have been involved in low-level drug trafficking. Others would undoubtedly like to be involved, but this is not large scale. In reality gang violence and chaos on the streets has formed a smokescreen behind which much more serious organized crime can operate, tying up police forces, undermining and overloading weak judicial systems, and filling up prisons. In 2006, this was eloquently expressed by Leonel Gomez, a former Salvadoran politician, investigator, and longtime ally of the United States, a close friend of successive U.S. ambassadors.

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency, he pointed out, estimated that 570 tons of cocaine went through the region the previous year, with a street value in the United States of about 300 billion dollars. Obviously the maras did not control this business. If they did they would not be living in slums and murdering each other for control of unpaved streets. But the maras served to sustain an “ambience of corruption” and chaos that has made it much easier for crime mafias to operate. And they are useful to hire if you need to kill anyone and make it look like petty crime.

The maras are part of a wave of urban violence, which, over the last 30 years, has spread between the United States and its southern neighbors, growing to the size and intensity of some wars. For anyone living in neighborhoods where the gangs operate, whether in the United States or Central America, their activities are devastating.

The violence has stunted economic development across Central America, in turn exacerbating social disintegration and illegal immigration to the United States. It has swamped weak and recently set up democratic, judicial, and police institutions, stopping them from working effectively.

Support for changing policing methods and reversing the militarization, must be another priority. This is not an impossible task. El Salvador has a national civilian police force, the formation of which was a central plank of the 1992 peace accords. Problems of police violence are far less ingrained in El Salvador than in countries like Brazil, where there was no reform at the end of military rule.

Central America’s appalling gang violence arose as an aftershock of the civil wars that tore the region apart in the 1980s. The truce between the Salvadoran maras now offers a second opportunity for initiatives to build a lasting peace, which were omitted in the 1990s. The central aim of any gang policy must be to try to wean those involved away from criminal activity into an alternative life. For this to happen in El Salvador there has to first be a truce. Otherwise gang members who leave are at greater risk of revenge attacks.

We believe that the mara leaders who negotiated the truce are serious. But because of the loose nature of gang leadership, they cannot easily force changes on their own organizations. The truce needs help from the Salvadoran population, the government, non-governmental organizations, and the international community, particularly communities and political structures based in the United States.

More than money and resources, a serious effort to end the violence needs creative ideas and needs to start quickly. We believe there is no viable alternative to a firm, enforceable truce between the gangs. Hardline solutions have made the problem worse and have not addressed the cycle of revenge at the heart of gang warfare. If the opportunities of the truce are missed, millions of people will be condemned to living indefinitely amid killing and violence.

Uzziel Peña was an urban guerrilla combatant during El Salvador’s civil war. He as since worked as a photographer and journalist, investigating for documentary teams and others visiting El Salvador.

Tom Gibb was for 20 years a BBC correspondent in Latin America, including ten years in El Salvador. He also worked for NPR, the New York Times, the Economist, and other media. Both authors have covered El Salvador’s gangs extensively over two decades.

Read the rest of NACLA's Summer 2013 issue: "Chavismo After Chávez: What Was Created? What Remains?"