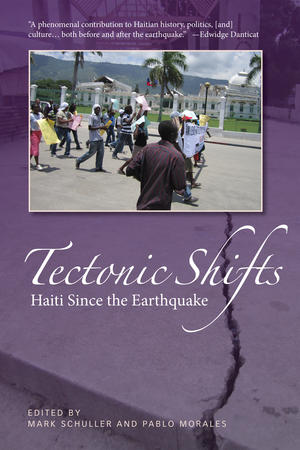

Tectonic Shifts: Haiti After the Earthquake, by Mark Schuller and Pablo Morales, eds. Kumarian Press, 2012, 271 pp., $24.95 (paperback)

A vital account of the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, Tectonic Shifts is a collection of 46 articles and essays by leading Haitian and international activists, scholars, and writers who are on the front lines of the struggle for meaningful relief and reconstruction. Through Tectonic Shifts, we meet key actors among the army of Haitian people and international supporters who have toiled in unimaginable difficulties since the earthquake to save lives, bring comfort to survivors, and rebuild a shattered country. We learn of the intense political and class struggle that is determining in whose interests the future Haiti will be guided and governed, a dynamic story shifting wrenchingly from one day’s news to the next.

In view of the limited and sharply criticized outcomes of the reconstruction effort to date, the book amounts to an urgent call for action and change.

Editors Mark Schuller and Pablo Morales (NACLA’s Associate Editor) pay tribute in their introduction to the Haitian tradition of youn ede lòt (helping one another): “The first emergency response came from the people themselves: Complete strangers pulling out children or the elderly half-buried under slabs of concrete. Neighbors pooling together what scraps of food, utensils, charcoal, and water they could find, sleeping next to one another on the ground. . . . This was the story of how the Haitian people put away their economic and political differences and worked together, in dignity and solidarity, to collectively survive.”

Youn ede lòt was ever present in the earthquake zone in those early weeks and then months. Its overarching presence was underreported and a startling contrast to the lurid stories of chaos and social violence that were invented by much of the international media. Haiti was said to be perched on a razor wire—on one side loomed descent into mayhem, on the other were the saving arms of foreign military and aid agencies. In reality, time and experience is proving that the Haitian people are the ultimate wellspring from which all hope for the country’s future rests.

The first third of the book explains how Haiti got to be so vulnerable to an earthquake whose geophysical force was far less than contemporary eruptions yet whose human consequences were catastrophic. “Like the motion of tectonic plates, Haiti’s disaster needs to be examined as a larger process, involving geopolitical structures and transnational tensions,” explain the editors.

The book includes a brief examination of Haiti’s 210-year, post-independence history, focusing on how the country was impoverished by policies of the big, imperial powers of the world. Focusing on recent decades, several essays examine how foreign, nongovernmental organizations have become ubiquitous to the provision of social needs that are rightfully the preserve and responsibility of national governments. Haitian professor Janil Lwijis (who died tragically hours before the earthquake struck) writes, “NGOs manage aid to develop capital in the heart and spirit of the poor masses—in other words, to disable workers.”

So how has relief and reconstruction stacked up? Tectonic Shifts details how ordinary Haitians have been frozen out of planning and decision-making processes that are flawed or do not even exist. Post-earthquake social conditions receive a large treatment in the book and tell a troubling tale. Residents of the vast camps of earthquake survivors that sprung up were thrust into a struggle for daily survival. Everything was and remains in short supply—potable water, sanitation and washing stations, food, employment, and other constructive social engagement. We hear from camp residents and lawyers and housing rights activists about the battles since 2010 for camp residents’ human rights and dignity. Hardship intensified following the reckless and unbelievable introduction of cholera to Haiti in October 2010 by the soldiers of the United- Nations military occupation force. The sanitation and potable drinking water deficit bequeathed to Haiti by decades of neocolonial neglect and interference became deadlier than most could have imagined.

Several chapters of Tectonic Shifts address the difficult conditions of women and girls. In Haiti, women bear the large share of responsibility for child rearing and keeping Haitian households together. A 2009 film, Poto Mitan, co-produced by Schuller, tells this story. Haiti’s earthquake not only killed people and destroyed buildings but also ruptured the social ties of family and neighborhood that sustain life and protect women and girls from the violence and discrimination of class society. (In addition to those reports cited in the book, a recent comprehensive report on womens’ rights is “Nobody Remembers Us,” by Human Rights Watch, August 2011.)

Is there an alternative course for post-earthquake assistance and a future for Haiti? This question is addressed in the final third of the book. The remarkable, final resolution of an international forum on housing that took place in 2011 in Haiti is published. It contains the essential elements of the housing program urgently needed and still almost entirely absent. It concludes, “We resolve to regain the sovereignty of our country in order to construct a society in which we can enjoy guaranteed access to housing and all our fundamental rights.” An essay by Fritz Deshommes, founder of the Haitian Association of Economists, explains that Haiti’s progressive Constitution of 1987 is an excellent guide for rebuilding the country, notably its guarantees of social rights, including housing. What’s needed, he writes, is “a true re-foundation of the state and nation.”

The book describes the two-round national election of November 2010 and March 2011 that brought Michel Martelly to the presidency. That election was a definitive sign that the mea culpas expressed by the large foreign powers in Haiti following the earthquake over their destructive policies of the past are next to meaningless. They funded and pressed upon Haiti an election in which the country’s most vital and representative political actors were excluded, including the Fanmi Lavalas party of former president Jean-Bertrand Aristide. The majority of the electorate itself was effectively excluded.

Incredibly, one year after this electoral exercise, Haiti has no effective government. The country lacks key ministries, such as housing. The elected president wants to entrench paramilitaries and former death squad leaders into national life by refounding the Haitian army, which was abolished in 1995.

The data contained in the latest monthly report (April 2012) of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs of the (OCHA) updates the ongoing emergency in Haiti that is documented in Tectonic Shifts:

• Many of the NGOs in Haiti operate outside of any coordination and accounting.

• Aid funding is drying up. Of the $238 million said to be needed for emergency aid in 2012, only $22 million, or 9%, has been delivered. Funding under the UN Consolidated Appeal Process in 2011 was $211 million, 55% of the declared goal.

• Some 14,000 houses have been repaired and more than 5,000 built since the earthquake, says the report. But that accounts for only 10% of damaged or destroyed buildings. And these are dwellings of home-owners, whereas the vast majority of dwellers in Port-au-Prince are renters or squatters. Six hundred thousand people are still living in the camps while hundreds of thousands more are living in damaged buildings or informal, unserviced settlements.

• Cholera remains a deadly threat as the rainy, spring season commences.

Tectonic Shifts offers no Pollyannaish prescriptions for Haiti. A hard struggle lies ahead if the country is to find a path of renewal and human development. But hope springs from its pages and from mounting evidence of renewal. Grassroots social and political movements are growing and their voices are rising. An example is the legal suit against the United Nations over the introduction of cholera. The justice of that case is recognized by all but the most hardened and blinded of Security Council officials and sycophants. Peasant organizations are alive and on the move to place agricultural development at the center of national planning.

The weak, unrepresentative government produced by the election of 2010–11 may soon run its course. The door is opening to a new round of struggle for democracy and representative government. In March, new agreements with Cuba, Venezuela, and other Latin American countries will see new or expanded programs in housing, health care, literacy, electrical and fuel provision, reforestation, and agriculture. Internationally, an important Haiti solidarity movement remains active and vigilant, giving voice to the aspirations of the Haitian people. More tectonic shifts are on the agenda in Haiti, this time in the social and political realm. They are too powerful to resist. Their path is sketched out in this important book.

Roger Annis is a coordinator of the Canada Haiti Action Network and resides in Vancouver, B.C. He directed an observation mission to Haiti in June 2011 and wrote several articles and reports on its findings.

Read the rest of NACLA’s Summer 2012 issue: “Latin America and the Global Economy.”