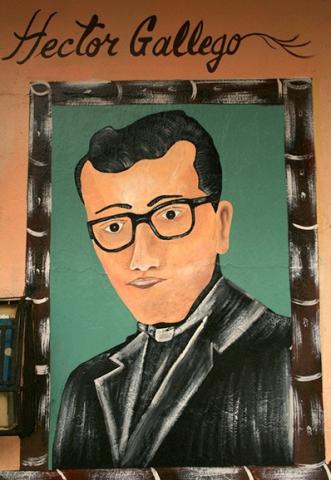

In June 1971, Panamanian plainclothes agents arrested Father Héctor Gallego, a young priest heading a Christian peasant movement in the country’s mountains. Thousands mobilized to demand Gallego’s safe release, while the military regime, scrambling to regain balance, ran a disinformation campaign, promising to “investigate” the matter and punish those responsible. The disappeared priest, today a folk hero, was never heard from again. In the early 1990s a democratic Panama tried and imprisoned a number of former intelligence (G2) agents involved in the case, but Gallego’s supporters, who have followed the twists and turns of the murky case for decades, remain unsatisfied. In the absence of hard evidence, conflicting rumors and unanswered questions about Gallego’s fate still circulate.

Panamanians have learned a tough lesson: that a country’s archives are often among the spoils of foreign invasion. Panama’s documents—all the documents from the country’s two decades (1968-1989) of military rule—are currently in the United States, seized during the 1989 U.S. assault and now hidden away from the public. As a result, much remains unknown about the history of Panama’s military regime. Interpretations diverge along partisan lines, but the debate is often shallow and lacking in details. There is relatively little rigorous scholarship on the military regime, so questions about its internal dynamics—say, how and why it moved from left to right, why its agrarian reform failed, or the role communist cadres played in shaping its policies—all remain unanswered for now.

Civil society efforts to clarify Panama’s past have had only mixed success. A truth commission (2001-2004), for example, never managed to identify the location of Father Gallego’s body, and families of many of the country’s 110 disappeared persons are still waiting to learn what happened to their loved ones. As Edilma, Father Gallego’s sister, told me in 2007:

The truth is a clarification of the facts. What happened with Father Gallego? ‘They buried him there.’ ‘They buried him in Cañazas.’ ‘No, they buried him in Tocumen.’ ‘No, because they threw him to the sea.’ ‘No, it’s that they buried him in Coiba.’ There’s a game of speculation with the pain one feels. It’s as simple as that.…It’s a drama that never ends.

In large part because its documents have been missing for so long, the military regime that disappeared Héctor Gallego is one of the least understood in Latin America. But there is now a real possibility that the documents will reappear. For one thing, declassified correspondence among various U.S. agencies, including the U.S. National Archives (NARA) and U.S. Army South, reveal that the collection is now seen as a liability. With that in mind, Panama’s new government is exploring the possibility of demanding that the documents be repatriated. This means that after decades, Panamanians may finally be able to learn about the enigmatic history of their country’s Cold War. They may also, decades later, have a chance to lay their ghosts to rest.

The basic outlines of Panama’s recent history are familiar. After seizing the state in 1968, General Omar Torrijos and his fellow officers consolidated power, crushing armed and unarmed resistance from the left and right. Following Gallego’s disappearance and the national crisis it created, and following a slowdown of the Panamanian economy soon after, Torrijos became politically vulnerable. His response was to define himself as a center-left, populist dictator, and to build significant bases of support in several sectors. Whereas in his first years in power, his men imprisoned, tortured, exiled, and sometimes murdered union activists, students, and journalists, by the mid-1970s the level of repression needed to sustain the regime dropped. And compared to other regimes in Central America, Torrijos was in the end moderate and relatively pragmatic, his regime excelling at negotiation, division of opponents, and cooptation.

Having defended Torrijos against a failed coup, Manuel Antonio Noriega, a general who Torrijos referred to as “mi gangster,” was put in charge of the regime’s network of repression. He centralized the state’s intelligence work, systematizing the G2 and police archives; he also, with other officers, enlarged and perfected a military-controlled transportation network, making it a kind of state-sponsored smuggling enterprise.

But if Noriega wielded the stick, Torrijos offered the carrot, bolstering his legitimacy both at home and internationally by passing progressive labor and land-reform legislation, supporting Nicaragua’s Sandinista Revolution, and signing the popular Torrijos-Carter Treaty, which would return the Canal Zone to Panama at the end of the millennium.

Torrijos was killed when his private jet exploded in midair in 1981, an explosion that coincided with a change of personnel and policy in the White House (though the cause of the blast remains unknown). By 1983, Noriega was able to take command of the country. Quickly, the planes carrying ammunition from Panama to Nicaragua changed direction, as Noriega began to actively support the U.S.-backed Contras. Noriega then increased his involvement with other international players. Colombia’s famed drug lord Pablo Escobar opened a large office in Panama City’s banking district, and protection and financial services for the Medellín organization soon provided Noriega with an immense source of revenue. At the same time, Noriega maintained a good relationship with the Cuban leadership, an arrangement that proved useful to several countries. Mike Harari, the Israeli who had headed Mossad’s operations department, relocated to Panama and became Noriega’s trusted friend.

But “Tony” Noriega’s most important friends were, of course, in Washington D.C. A CIA asset since his days as a military cadet, Noriega became irreplaceable as Panama’s intelligence chief, and later, dictator. It was not only the information he could supply, but the tasks Noriega could perform for Washington, that made him valuable. Mediating with Fidel Castro, shipping arms to the Contras, Noriega dutifully helped his U.S. benefactors, and along the way, gained more information, money, and power.

How Noriega turned from a key asset to a foe, threatening enough to warrant a full-scale invasion, is a story that is complex and, without much in the way of documentation, still somewhat enigmatic. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) gained strength as the War on Drugs took center stage in U.S. foreign policy. While throughout the 1980s, the CIA had aided drug traffickers and money launderers, like Noriega, who were useful to its Cold War efforts, by the end of the decade, the DEA could argue that Noriega’s support for Colombian cartels was too much of a liability.

In Panama, opposition groups began to unite. Under fire, Noriega ratcheted up his anti-imperialist rhetoric and began to seek support from unexpected sources after barely surviving an attempted coup by his own officers in 1988. Sandinista and Cuban advisers soon helped him train his special forces and arm his Dignity Battalions, a “peoples’ militia.” Negotiations were underway with Libya to secure anti-tank weapons; there were also some contacts with the Palestinians. In the last two years of Noriega’s rule, even his staunchest supporters in the CIA lost faith in the Machiavellian prince they had cultivated for so long.

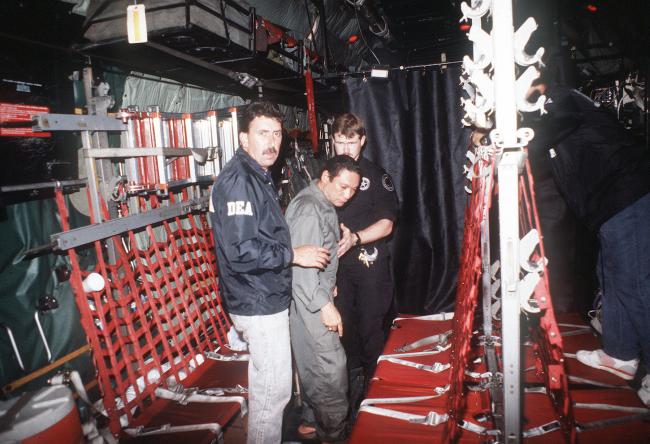

On December 20, 1989, U.S. forces invaded Panama in Operation Just Cause. (In Panama, it is sometimes called “Just Because.”) The Panamanian forces—a militarized police at best—were not capable of mounting an organized defense of their country. While the U.S. military machine pounded Panama City, fires raging in the working-class neighborhood of El Chorrillo trapped thousands. In the next days, while U.S. forces pushed into the interior, military police units struggled to enforce authority over the main cities. The public sacked the city’s shops while the smell of charred bodies was still in the air.

U.S. military intelligence units, meanwhile, snatched the regime’s files. In all, they took an estimated six million documents: 15 thousand boxes’ worth, found in military barracks, G2 archives, government buildings, and in Noriega’s apartments. The Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) boasted in a secret memo to the Deputy National Security Adviser in 1990 that its “exploitation team has reviewed a considerable amount of personal correspondence, bank statements/transfers, travel records indicating shipment of illegal aliens, arms inventories, policy letters, stolen U.S. documents, personal checking accounts, election ballots, letters to and from commercial firms, PDF G-2 reports on enemies of the government, and other like material.” (See “Background Paper for the Deputy National Security Advisor to the President, National Security Council,” available at the George H.W. Bush Presidential Library.)

CIA agents reportedly tried to take possession of the collection before the soldiers could; meanwhile, a trial was being prepared for Noriega in Florida. In the trial, which took place in April 1992, American prosecutors would have to convince the public that Noriega should be imprisoned for drug trafficking—but without touching on the direct role the United States had played in his crimes. Concerns were thus raised that the CIA or Army intelligence might eliminate inconvenient documents. According to a recently declassified National Archive memo, the army created two full copies of the collection for safekeeping, and various agencies received copies of parts of it.

While the United States was prosecuting Noriega, the elected, U.S.-sponsored government of Guillermo Endara slowly gained stability in Panama, in part by taking care not to scratch too deeply beneath the surface of Noriega’s time in power. There were trials for human rights abuses, but there was never a sense that all or even most of the regime’s crimes were being investigated. In part, this was due to the nature of the political consensus reached after 1989—justice was a compromise that depended on more urgent political needs. According to declassified State Department dispatches, a process was set in place to allow a number of Panamanians, handpicked by the Endara government, access to the documents, which were stored in a building in the Canal Zone. The process was extremely cumbersome, however, and it is unclear how many Panamanians actually saw the documents.

The government, meanwhile, was made up of people who had fought the human rights abuses under Noriega, and on whom Noriega had been collecting information for two decades. When interviewed by journalists, President Endara frankly admitted he did not want the documents in Panamanian hands. “Yellow journalists would have a field day with them,” he told a Miami Herald reporter. “ I don’t want these documents to be used to allege that so-and-so is homosexual, so-and-so is lesbian, or so-and-so cheats on his wife.”

Behind the scenes, the U.S. government finally offered to return the documents to Panama in 1993, but the Panamanian government declined to take up the offer. The U.S. government retained the documents, treating them as though they were Panamanian property, “on loan” to the United States. Panama was still suffering from the recession of the last years of Noriega’s rule and licking its wounds from the U.S. invasion. It is thus not surprising that the very same people who clamored for free speech under Noriega suddenly did all they could to limit the public debate over access to information.

In 2007, I filed Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to various U.S. agencies for documents from this collection. I received flat denials that the documents even existed. Rafael Pérez Jaramillo, who led the Panamanian Truth Commission six years earlier, explained that, over time, official channels for locating and accessing the documents became more and more opaque. In the mid-1990s, the collection was moved to Albany, Georgia, left in the custody of the U.S. Army. Early in 2001, after applying some pressure, the Truth Commission received an invitation to consult the documents in the United States. Following 9/11, however, the invitation was indefinitely delayed. Ultimately, the Truth Commission was told it would have to file Freedom of Information requests for specific documents, like any other person.

In conversations I had with the relevant units following my FOIA requests, officers always told me they had never heard of the Panamanian collection. It’s possible that they were not lying. Following a FOIA request to the U.S. National Archives, filed by CUNY law professor Douglas Cox, it was revealed that the collection had most likely been lost for over a decade, only reappearing when a U.S. Army South commander received an unexpected bill of $64,000 from the depot at Georgia for a decade of storage. Almost simultaneously, librarians of the Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO) in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas contacted the NARA for advice about a collection of microfilms they had—the army’s copies of the original collection. Today, the files are still in U.S. hands, but, from their correspondence with NARA, it seems that these U.S. agencies no longer have any use for the collection.

As a result, a number of civil society organizations are pressuring the Panamanian government to demand the archives’ repatriation. If they succeed, a series of practical, legal, and political questions, mainly involving privacy rights, will have to be resolved if the public is to be allowed to access the records. Panama will have to strike a balance between protecting citizen privacy, deepening the debate about the military period, and prosecuting past crimes.

Meanwhile, more mundane considerations may determine the fate of the documents. For one thing, since the microfilm collections held in the United States are considered U.S. property, it is likely that they will be declassified and moved to the National Archives in Washington, D.C. While few Panamanians will have access to them, opening the microfilms could make the original documents less threatening. However, as Panamanian activists I have collaborated with have noted, it will be hard to find an institution that the public can trust with maintaining the integrity of the collection, protecting the privacy of citizens, and fairly adjudicating which information should or should not be disclosed, given a climate of weak legal structures and high levels of corruption within the government.

And yet, while the logistical hurdles are daunting, the real question is whether Panama, which is now undergoing the longest period of economic growth and political stability in its history, is finally ready to reclaim its troubled past.

In his final sermon, Father Gallego, having just survived an attempt on his life, told his followers, “if I disappear, don’t go looking for me. Keep fighting.” While his followers did begin a massive non-violent campaign to demand the priest’s return after his disappearance, they heeded his plea to continue the struggle for social justice in Panama. But at the same time, they never abandoned the hope that they would, one day, find out what had happened to their leader. Today, the clues to Gallego’s fate, and to the fates of the other Panamanians killed and disappeared by the military regime, likely lie in Panamá’s stolen archive. It is time for the files to be opened.

Originally from Israel, Ezer Vierba completed his Ph.D. in history at Yale, where he wrote his dissertation on punishment and power in modern Panama. Currently, he teaches Latin American history in Harvard’s History and Literature Program.

Read the rest of NACLA's 2014 Fall Issue: Horizontalism & Autonomy