Click here to purchase Leandro Viana's prints.

In order to comprehend the scope and significance of the work of Leandro Viana we must begin with an awareness of Brazil as a receiving country for regional migrations. Above all, we must understand the cultural significance of the sizable migratory flows of Bolivians into the city of São Paulo. The Bolivian immigrants, who are an increasingly visible presence in the city, suffer from stereotypes stemming from their indigenous background and their migration from a poor country. While the receiving society reproduces racism and discrimination on the basis of difference, the response of the migrant community has been music, dance, and art.

Since 1970, Brazil has received international migration flows from Latin America and the Caribbean, above all from nearby South American countries. Census data from the year 2000 indicate that there were 118,585 immigrants living in Brazil who were born in Latin America or the Caribbean. Of these, 20,322 were born in Bolivia. Approximately 10% of this Bolivian population arrived prior to the 1960s, with increased flows in the 1970s, and the largest share of migrants arriving after 1990.

In the last 30 years, as Brazil has increasingly become a destination for Latin American migrants, this flow has primarily been directed toward urban areas, especially São Paulo. The image of São Paulo as “a city of a thousand peoples” is a source of pride, as well as being the largest of all cities in Brazil and the capital of São Paulo state. Since the end of the 19th century, the history of São Paulo has been marked by migration cycles that have transformed the city demographically and spatially with each ensuing wave. This process has made São Paulo one of the most diverse cities in Latin America. This variety—of physical appearances, traditions, religions, and accents—is one of the defining characteristics of São Paulo. Residents of the city are known to boast of their demographic diversity and the supposed ability of this society to receive strangers. Today, São Paulo continues to be a magnet for arriving foreigners, often in search of work, as is the case of Bolivian immigrants to the city since the 1980s.

Bolivians make up the largest community of South American immigrants in São Paulo. The undocumented nature of these migrations over recent decades makes measurement difficult, but the presence of Bolivian migrants in the city and the larger metropolitan area is noticeable to all. This widespread recognition would also appear to confirm the argument that official data do not reflect the real magnitude of these flows and tend to underestimate the presence of Bolivians.

The presence of Bolivian immigrants in São Paulo is not a new phenomenon; Bolivian students migrated to Brazil in the 1950s as part of the scientific and cultural exchange agreements between the two countries. During this period, some Bolivian migrants also came to Brazil for economic or political reasons, seeking employment opportunities or freedom from repression. Many of these students stayed in Brazil.

Beginning in 1980 there was a significant increase in the flow of Bolivian migrants to São Paulo. In this period, migrants, for the most part, were neither students nor political refugees but rather persons with a low level of education in search of work. This migration occurred as Bolivia was facing a serious economic crisis, aggravated by the neoliberal reforms that privatized the Bolivian mining sector, thereby producing high levels of unemployment. In the 1980s, the average immigrant, whether male or female, was young, single, with a medium level of education, largely of rural origin, and was attracted to São Paulo by the promise of good salaries in the garment industry. They came primarily from the Bolivian states of La Paz and Cochabamba. In some cases members of the family, including parents, gradually emigrated as part of a process of family reunification. The economic activities of these migrants were concentrated in the sewing industry.

Beginning in the 1990s, the Bolivian presence began to concentrate in the central region of São Paulo, in neighborhoods such as Bom Retiro, Brás and Pari that housed garment production and retail facilities. With the increasing demand for labor to sew garments came an ongoing arrival of Bolivians—increasingly female—that continues to this day. In a parallel process of change in the garment industry that began in the 1980s, Bolivians began to be hired as temporary workers without any workplace regulation and faced vulnerability both because of their undocumented status as well as their employment in the informal sector. This also created a situation in which some Bolivians began to operate as intermediaries between domestic employers and the Bolivian laborers who worked in establishments across the city. Workplace abuses became increasingly common in this precarious environment, and this led the Brazilian media to consistently denounce the situation as one in which Bolivians were working and living in slave-like conditions.

Bolivian immigrants, however, tend not to recognize themselves in the situation described by the media and feel deeply uncomfortable with the negative images created by the Brazilian press. These images of Bolivians: as “slaves,” as “enticers” of others to work in inhumane conditions, and as “unscrupulous employers” who force fellow Bolivians to live in deplorable conditions or even inside sewing factories (something that has indeed occurred)—has troubled many Bolivian residents in São Paulo. In response, the Bolivian community, in addition to organizing to improve conditions, has established social and cultural organizations with the goal of promoting a positive image of itself.

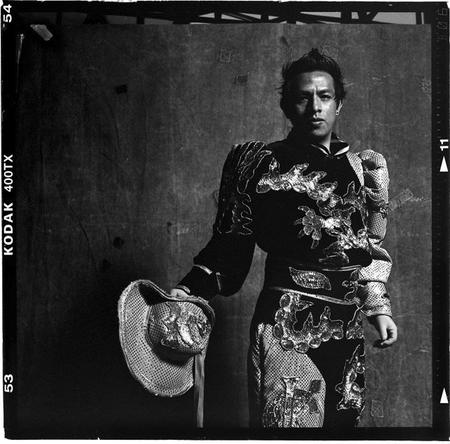

This is where the work of Leandro Viana enters the scenario. Viana photographs festivals, both sacred and irreverent, that depict moments of devotion and pleasure of the Bolivian community. These photographs represent a portrait of peoples and of cultural expressions of the Bolivian community. They allow us to visualize the Bolivian community as it sees itself and as it wants to be seen by the receiving society.

The organizations that were created over recent years include the Father Bento Gastronomic, Cultural and Folkloric Association, and the Bolivia-Brazil Cultural Association of Folkloric Groups and Musical Ensembles.

The Father Bento Association was established in 2002 to organize the cultural events of the Bolivian community that have taken place since then in the city square referred to as Praça Kantuta in the Pari neighborhood of São Paulo. This includes the Sunday fair that has become the stage of large Bolivian cultural events such as the Fiesta de Alasitas and which is recognized in the city as a meeting place of immigrants. Both the name of the square and the fair activities have since been officially recognized by the city of São Paulo. The fair takes place on Sundays from 11am to 7pm and presents a range of Bolivian items to visitors. Stands offer typical Bolivian food, artisan crafts, places to have photos taken, Bolivian music and films, hairdressers, phone cards to call home to Bolivia, and announcements of employment. Two thousand people, some 90% of whom are Bolivians, normally visit Praça Kantuta every Sunday, and on festival days the number of visitors can reach up to five thousand people. The fair is a setting where Bolivian immigrants and their descendants go to meet, have fun, eat traditional food, find both work and romance, and play soccer. In short, it is a social and leisure setting among countrymen and women. The fair has served to strengthen the identity of Bolivians in São Paulo as well as to portray a positive image to those outside the community.

The Brazil-Bolivia Cultural Association organizes events that take place in the Memorial of Latin America, located in the São Paulo neighborhood of Barra Funda. These national festivals of devotion in the Memorial reflect an effort to negotiate a positive image of the Bolivian community in São Paulo and, little by little, are establishing what Bolivians view as a legitimate portrait of themselves as part of this society. The Bolivian Consulate in the city has contributed in a decisive way to the organization of festivals in the Memorial by mediating the relations between the association and the foundation that manages this center. The memorial celebration has reunited Bolivian immigrants of all strata, both those who have recently arrived as well as those who have settled in São Paulo since the 1970s. The festivities have a strong civic character since events center on the commemoration of national independence and extend beyond the religious significance of devotional festivals.

In both the Praça Kantuta and the Memorial of Latin America, folkloric groups dance morenada, caporal, tinku, diablada, llamarada, kullawada, and other dances that are traditional aspects of Bolivian festivals—in particular the carnival in the Bolivian city of Oruro that was declared by UNESCO to be a “Cultural Heritage” site in 2001. Cultural events characterized by glittering clothes and music full of references to Bolivian history are reproduced by these groups in the setting of São Paulo in order to construct a new image of Bolivians. These groups seek to show the best of their cultural events so that the residents of São Paulo view the Bolivian community in a positive light and recognize how much this group can contribute to the cultural diversity that defines this “city of a thousand peoples.”

In the end, it is these groups’ efforts for positive recognition that Viana captures in his work—producing images that do not indicate effort so much as a people just being who they are. Because no human being is characterized in only one dimension, everyone is the outcome of an encounter of different facets based on culture, class, and origin. We are composed of plural and fluid identities that are “defined” through relations that depend on whom we interact with and how we seek to appear. Bolivians in São Paulo merely want to be seen as they are, as people.

Originally from São Paulo, Brazil, Leandro Viana is a freelance documentary photographer based in New York City. After breaking into the field through fashion, editorial, and advertising photography, most notably at DPZ, one of Brazil’s leading advertising agencies, Leandro began documenting social issues such as immigration, refugees, and human rights. His series documenting Bolivian migration in São Paulo (pictured here) was awarded the 2011 Conrado Wessel Award in Brazil and was featured at the Chobi Mela International Festival of Photography in January 2013.

Caroline Cotta de Mello Freitas holds a PhD in Social Anthropology from the University of São Paulo. Her dissertation concerns the rights of indigenous people within the Plurinational State of Bolivia. She currently works as a researcher and professor in the São Paulo School of Sociology and Politics (FESPSP). Translated from the Portuguese by Lee Mackey.