Leonardo Padura Fuentes was born in Havana and grew up in the dusty popular neighborhood of Mantilla, in the south of the city where his grandfather was born. He studied at the local pre-university and then at the University of Havana—philology and Latin American literature, though he wanted journalism. Padura developed a style of “literary journalism,” writing portraits of cultural figures for two well-respected magazines. He is internationally known for a series of seven detective novels whose protagonist, Mario Conde or “The Count,” finally breaks away from years with the Havana Police Department to sell second-hand books in the Plaza de Armas in the old city with the hope of becoming a writer. Each of the novels (and Padura is working on the next one) follows Conde’s life with his pals and his professional contacts as he struggles with his job and his dream. Each book contains an intriguing crime story. Each examines a theme of the Cuban realty during the 1990s, the deep depression that the island suffered after the dissolution of the USSR and the tightening of the U.S. blockade.

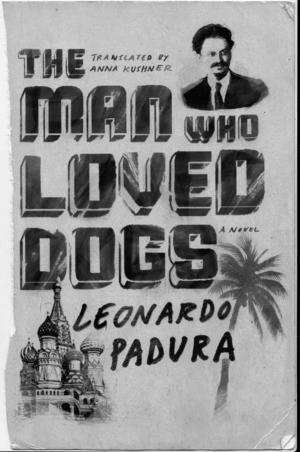

Padura’s other works include an early romance novel as well as two literary biographies, many essays, short stories, pieces of literary criticism and cultural analysis as well as scripts for movies. He received the UNEAC prize for the best Cuban novel in 1993, and the International Dashiell Hammet prize for the best detective novel in 2006, among other prestigious awards. Padura took 12 years to think about, research and write El Hombre que Amaba a los Perros. It was first published by Editorial Tusquets in Barcelona in 2009. Tusquets also published an edition in Mexico. In all, there have been six editions and three re-printings from that publisher. A herculean task to translate, it has been faithfully rendered into English by Anna Kushner. At over 600 pages and called a novel, the book is an ambitious example of Padura’s fusion of documentation, speculation and fiction—part political history and part creative writing. The mix is often compelling, though sometimes confusing.

The three protagonists of the book, Ramon Mercader, Ivan Maturell and Leon Trotsky, all loved dogs. Mercader, who murdered Trotsky in August 1940, died in Cuba in 1978. He is the one explicitly referred to in the title. Ivan Maturell, a fictional creation of the author, is the first person narrator, a Cuban writer who, while walking on the beach east of Havana in 1974, meets a frail, older man with two Russian wolfhounds who tells him the story of Trotsky’s assassin. What we are reading is purportedly the book that Ivan has finally written—from his experiences with the man, from documents others give him, and from a study of the times through which Mercader and Trotsky lived. Details of Trotsky’s life in exile are included in separate chapters. The dramatic tension that excites the reader builds the story from 1920 through the 1940s—Trotsky’s exile at the same time as Mercader’s preparation by the Stalinist cadre to kill him. Padura’s characterization of both men is a vivid and insightful inquiry into fanaticism—the psychology of ideology.

Mercader’s moral development within his bourgeois Catalan family during the 1920s and into the epoch of the Spanish Civil War shows the writer’s skill at it’s highest. Ramon’s relationship with his mother is a convincing portrayal of how hatred can be transmitted from one generation to the next.

“[H]is mother gave him one of those wet kisses that, when he was a child, she used to deposit at the corner of his mouth so that the sweet taste of saliva, with its lingering taste of anisette, would drip down his taste buds and cause the overwhelming need to keep it in his mouth for longer than the process of his own secretions would allow.” The hatred she developed after being abused by her bourgeois husband, Ramon’s father, thus infects the son. Their emotions fold both into ideological obsession with Communism’s ability to end the power of one class over another. It then takes the form of defending the Soviet Revolution, denying and denying and denying what goes on after Stalin seizes power.

Trotsky is presented as humane, and also obsessed. He watches his family and his followers murdered, and he maintains the sense of his mission to save humanity by defending Soviet Communism against all assaults despite the atrocities committed in its name by Stalin, and the factionalism that splits and splits and splits. As for Ivan, in an interview last year, Padura told me “Ivan is not a man; Ivan is the synthesis of a generation.” He is presented throughout as a damaged soul floundering in the existential vacuum of an unfulfilled life. Even when he receives the gift of the story of the century to write, he is confused by his own compassion for the murderer.

*

Since Padura is arguably the most important living Cuban writer, we would expect this highly political novel to contain his perception of how Stalinism affected his own country. But the novel lacks Cuban historical details like those that are so gripping in the recounting of Mercader’s experiences during the Spanish Civil War and Trotsky’s during his exile. We are left to draw inferences about Cuban policies that are confusing and can be misleading. A serious political problem is that in this highly charged historical docudrama about the failures of Communism, no mention is made of the United States. No reference is made to the Cold War, which placed the Cuban Revolution between a rock and a hard place.

We in the United States have been deluged with condemnation of Communism and the terrors of the Soviet era. The continuation of the Cold War aspects of the U.S. blockade against Cuba are rarely discussed in U.S. mass media, and consequently poorly understood. Debates about Cuba fall into denunciation versus defense, with sensible solidarity too frequently drowned out. Thus a serious problem with the narrative in this book is also a serious failing in the political analysis. Without chronicling the assaults from the North, the book in the hands of the remaining radical reactionary exiles waiting to reclaim the island could be taken as evidence that Padura believes the Soviet influence led to all the problems that have confronted Cuba since the Revolution.

Two cases in point come from two of Ivan’s experiences, which take a chapter each: his brother’s expulsion from medical school for being homosexual during the repressive 1970s, and the rafters’ exodus from the north coast during the deep depression of the 1990s. Neither moves the narrative or historical thrust of the book forward.

As we know, the struggle for sexual liberation and freedom to choose one’s life-style is not limited to Cuba. Because chronology in the Ivan chapters jumps around, the impression remains that these repressive attitudes were unique to Cuba and that they continue. Now however, and at the time of Padura’s writing, Mariela Castro (Raúl’s daughter) heads a militant movement against homophobia.

As for the rafters’ departure, which Ivan witnesses in the mid-1990s, we must keep in mind the push-pull during that decade. The push came from the reeling Cuban economy following the collapse of the Soviet Union and its sizable annual subsidies, accompanied by the U.S. economic blockade. The pull northward came in the form of U.S. immigration policy, which broke U.S. laws to invite Cubans to risk the Florida Straits. Residual Cold War policy towards the island still rewards illegal immigrants from Cuba. Since the mid-1960s all U.S. administrations have offered Cubans “refugee status” when they arrive in U.S. territory. Especially during the 1990s, this tempting offer led to many deaths. U.S. corporate media uses the flight of so many in accusatory propaganda as proof of all the awful things Fidel Castro has done, which make it necessary for ordinary folks to flee. Padura’s portrayal of this exodus within the story of the failure of Communism ignores the Cold War and the role of the United States, and that seriously distorts Cuban history.

*

Padura, however, says he wrote the book for a Cuban audience. Cubans are bombarded with slogans on billboards and news analysis on the nightly Round Table condemning U.S. imperialism. So much blaming has led to skepticism in the population and an assumption that their government uses external forces as whipping boys to avoid taking responsibility for their own decisions and mistakes. What has been hidden in Cuba during all the years during and after the Cold War is information about Stalin’s barbarity and the failures of Soviet Communism. Because these were hidden, Cuban intellectuals and the educated public, hungry for serious reading, have responded to the book with appreciation.

The publishing arm of the Artists and Writers Union of Cuba (UNEAC) put out the Cuban edition in 2011. In 2012, the book received the National Prize for Literature. Four thousand copies were printed with 2,000 offered to members of that prestigious organization of artists and intellectuals. Two thousand copies were distributed to the population. Of those, a good number found their way to the second-hand book market where they sell for about 375 Cuban pesos. To put that price in perspective, a teacher earns about 500 pesos a month. So the book is very costly for Cubans who receive free health care, schooling and social services but have little spare cash for personal items like a book. Copies that find their way in from abroad are also prohibitively expensive. Journalists, artists and professors wait for one to be passed around. A reprint is expected, but paper is precious and the economy is weak.

For this reviewer, the most profound insights of the book concern the intimate human interaction between Mercader and his Cuban witness. In Ivan’s and his friend Dany’s reflections, we discover how the witness struggles to contain his contradictory feelings after hearing about the complex life of a political hit man. When Ivan first meets him, Mercader is a mysterious and pathetic figure. The young man is intrigued, and they continue to meet until mutual confidence is established. “Mercader was a victim, like most of them,” says Ivan (p. 564). “I was fully conscious that Ramon Mercader was causing me, more than anyone else, that inappropriate feeling which he himself rejected and that frightened me by the mere fact of feeling it: compassion” (p. 406). Compassion, here, is an antidote to ideological fanaticism. The writer confronts us with the challenge of being fully human in the balance between compassionate understanding and moral clarity, even when contemplating a thoroughly reprehensible act. Another challenge is finding individual meaning in one’s life when the unifying vision for creating a better world has dimmed.

As a devotee of Padura’s detective novels, I felt honored to interview him before the English translation was completed. I would have been delighted to unconditionally recommend the book, but the narrative and political flaws restrain my enthusiasm. I am afraid that for U.S. readers looking for insight into Cuban society, the book will generate more heat than light. The sections about Trotsky, however, will re-stimulate a healthy debate; the speculation about Ramon Mercader will be a gift to historians and psychologists; and all readers will benefit from contemplating another interpretation of how humanity fell ill during an epidemic outbreak of hate and fear in the middle of the twentieth century.

Susan Metz is a writer and an independent researcher living in Brooklyn, N.Y. She has taught Playback Theatre in Cuba for 13 years.

Read the rest of NACLA's Winter 2013 issue: "Latino New York"