This piece was published in the Summer 2013 issue of the NACLA Report.

Last October I arrived in Venezuela a few days prior to the election to try to get a sense of what people were thinking and—since I work for a union—what labor conditions were like in the country. Over breakfast one morning, I asked our waiter what the minimum wage was in Venezuela. During the conversation that followed, I discovered that William Orozco was not only extremely knowledgeable but also that he was an officer in a hotel workers union! Since he was on the clock, we agreed to meet later and the following day he arrived with Leonardo Peroza, the general secretary of his union and also a hotel worker. After an interesting discussion, we parted ways, agreeing to stay in touch.

When I learned that the National Lawyers Guild had been invited to send a delegation to monitor the April election and that I had been asked to participate, I wrote to the Venezuelan trade unionists to let them know that I would be back. William responded warmly and invited me to resume our chat.

Beginning the night before the election no alcohol can be sold, so we spent several hours over lemonade in the bar of my hotel. Our discussion ranged from the election—they were certain that Maduro would win by a large margin—to labor issues. They had recently been recognized to represent 176 workers at a neighboring hotel and enthusiastically told me about the first contract that they had just settled there that included both great vacation benefits and profit-sharing. The next step, they explained, was to have a meeting of the workers in which a majority would have to approve the contract in a secret vote. They were clearly proud of the democratic nature of their union, explaining that in the union they had previously belonged to they would have been informed about the terms of their contract and anyone who protested would have been fired. I asked what would happen if the new contract was voted down. They were confident that the workers would approve the new agreement, but said that if not they would be back at the negotiation table. They added that because of the timing, the vote would take place after the election and explained that the “bosses’ last card” was that opposition candidate Henrique Capriles would win and undo the new labor law that provided support for many of the improvements in the contract.

This led to a detailed discussion of the provisions of the new labor code that had been proclaimed in April 2012. Some important parts of the law are already in effect, including provisions that limit the reasons for discharges and place the burden on the employer to demonstrate cause before an office of the Ministry of Labor prior to firing a worker. Although not all employers comply with the new law, they must reinstate the worker with back pay prior to any appeal and can be imprisoned if they disobey an order to do so.

Characterized by employers as leading to the “death of their companies,” provisions of the new law effective on May 7, 2013 increase vacations from a minimum of 15 days up to 30 paid days after 16 years of employment plus an additional vacation bonus ranging from a minimum of 22 up to 30 days’ pay. Profit sharing also begins at 15 days pay and increases to 30 under the terms of the new law. Pregnancy leave has increased to six weeks prior to birth and 20 weeks following delivery.

Other provisions include a shorter work week and—of particular importance to workers in hotels and restaurants—require employers to provide two consecutive days off to all workers who are employed for at least seven hours a day for five days during a week. One extremely important provision is scheduled to be implemented three years after passage: a requirement that would entirely do away with contingent work or sub-contracting, preventing employers from avoiding payment of mandatory benefits. In addition, they told me that by December 31 all unions must hold internal elections and provide transparent accounting of their finances or they would lose the right to negotiate contracts. They explained that this would eliminate undemocratic unions where “people have been general secretary for 30 years without ever being elected.”

But they also observed that there are no guarantees of success. There are still employers who fire workers for trying to organize, who have them sign blank resignation forms when they are hired, or who have workers acknowledge receiving a certain amount as pay when they actually receive less. Quoting Simón Bolívar that “man is dominated more by ignorance than by force,” they assured me that they were hard at work helping workers to “open their eyes and organize.” I told them about the work of my union, the UE, and that we were also hard at work educating and organizing workers in the United States.

Following the election, they wrote to say how much they had enjoyed our meeting, that they had won the election although not by the margin they had expected, and that they sent “a warm embrace full of affection” to me, to members of my organization, and “especially to the people of the United States, who are our brothers and sisters.”

Robin Alexander is Director of International Affairs for the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE).

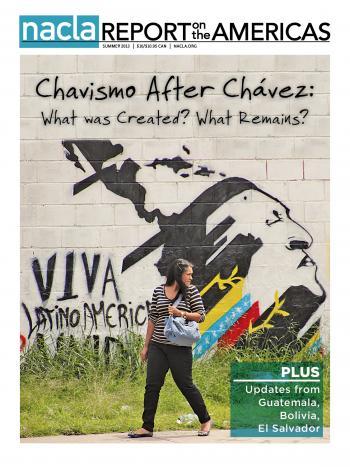

Read the rest of NACLA's Summer 2013 issue: "Chavismo After Chávez: What Was Created? What Remains?"