Coca Brynco is the newest addition to an assortment of coca-infused drinks produced in the Andes—all of which are illegal to bring into or sell in the United States. Marketing of the drink began in January, perhaps to coincide with Bolivia’s proposal to the United Nations that coca leaves should not be targeted for international drug control (see my last post). The drink, and perhaps more obviously its Bolivian predecessor Coca Colla, has enormous symbolic (and its makers hope commercial) power as a direct challenge to US-manufactured Coca-Cola and all that it represents—including US economic hegemony and the dictates of drug control. In a news conference shortly after being elected, Bolivian President Evo Morales made this link explicit: “It is not possible that the coca leaf can be legal for Coca Cola and not for us. It’s hypocritical.”

Across the region indigenous communities have challenged prohibitions on the commercialization of coca. Over half a decade ago, an indigenous community in Southern Colombia began manufacturing and marketing coca-based products including Coca-Sek, a citrus flavored soft drink, despite laws in that country which limit the coca leaf’s legal use to “traditional, not commercial ends.” The argument that traditional uses of coca need to be protected can be used to limit any other uses of the leaf (at least within the Andes), meaning indigenous communities’ relationship to the leaf implies that they should be locked in time, excluded from participation in the global market. This argument is rooted in colonial arrogance toward indigenous peoples reconfigured by the professed (if patronizing) desire of contemporary drug warriors to promote health and security.

When I was conducting research in Peru in 2002 I spoke with the then President of ENACO, the government-controlled monopoly which manufactures and markets coca-based products. He explained that despite earnest attempts to market the company’s products in the United States, all proposals had been forcefully rejected. Even those products from which all the cocaine alkaloid had been extracted were illegal, as the US government explained, because they inevitably would contain trace amounts of that banned substance (an obstacle overcome, it should be noted, by the pharmaceutical company which process the leaves destined for bottles of Coca Cola.) To my best knowledge the exclusion of Andean-produced coca products from the US market remains in place to this day.

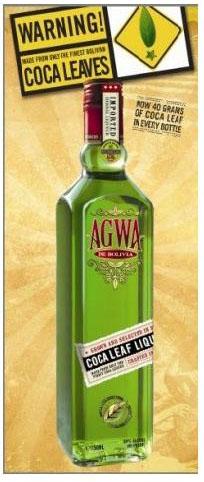

So I was stunned a few months ago when a friend handed me a bottle of a coca-infused alcoholic beverage: Agwa de Bolivia. Crafted in Amsterdam, this green “coca herbal liqueur”, the bottle boasts, is “made from only the finest coca leaves” which are “grown and selected in Bolivia.” The bottle had been purchased perfectly legally from a local liquor store, which also was distributing stacks of promotional items advertising the uniqueness of this “exotic” drink. The hierarchy of participation in the global drug marketplace is starkly on display. Not only does this European-manufactured coca drink have access to the United States market, but it capitalizes on cocaine’s danger and shock value to sell its product. One poster flaunts a bold “WARNING! Coca Leaves” sign while the bumper sticker (also available in poster-format) declares: “Melts in Your Mouth, Not in Your Nose.”