Writing from Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago

Over the last decade the Caribbean has become one of the major trafficking routes for drugs leaving South America destined for the United States and other consumer markets. The International Narcotics Control Board estimates that profits from this lucrative industry exceed that of the entire region’s legal economy. As the United States funds militarized drug war policies from Mexico, through Central America, Colombia and across the South American continent, drug traffickers diversify their routes, shifting to other geographic passageways. The U.S. government attributes the rise of the drug traffic in the Caribbean to what it describes as the “success” of its policies in Mexico and Central America. In response, in May 2010 the Obama administration launched the Caribbean Basin Security Initiative (CBSI) to coordinate drug control strategies in the region. (It is worth noting that today a counterpart initiative, the Central American Security Strategy, is being launched in Guatemala.)

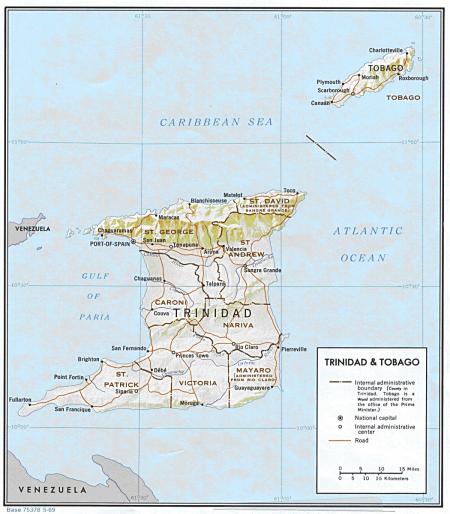

The twin island nation of Trinidad and Tobago (T & T), a place I am currently visiting for the first time, presents a sobering case study on the failures of the punitive approach to drug control advocated and funded by the United States.  Last year the U.S. Congress appropriated for the CBSI no less than $37 million. According to the U.S. State Department, as part of its war on drugs, the U.S. government provides training, equipment and technical assistance to the government of Trinidad and Tobago through a wide array of agencies including the Drug Enforcement Administration, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the Federal Bureau of Investigation the Coast Guard and the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs.

Last year the U.S. Congress appropriated for the CBSI no less than $37 million. According to the U.S. State Department, as part of its war on drugs, the U.S. government provides training, equipment and technical assistance to the government of Trinidad and Tobago through a wide array of agencies including the Drug Enforcement Administration, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the Federal Bureau of Investigation the Coast Guard and the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs.

The impact has been devastating.

Dorn Townsend, a freelance reporter, consultant and journeyman spokesperson for the United Nations describes the situation in Trinidad and Tobago with the words, “welcome to the world’s newest narcostate.” And the picture he paints is grim. In an article in Foreign Policy and a research paper published by the Small Arms Survey of the Graduate Institute of International Development, Townsend documents how the murder rate in the country has risen by 400% in the last decade alone, gaining T&T the dubious distinction of overtaking Jamaica as the murder-capital in the region. He links this violence directly to the drug trade and the trafficking in weapons which accompanies it. Geographically situated less than 15 miles from the coast of Venezuela the country has become a major transit site for South American cocaine, and to a lesser extent, other controlled substances. The majority of illicit drugs pass through the islands on their way to other destinations, reaping windfall profits for an elite group of criminal barons with alleged ties to the highest echelons of political power—although the exact nature of their national and/or international identity remains a mystery. At the lower levels of the trade, as gangs compete for control over the local market, huge numbers of poor, primarily Afro-Trinidadian young men disproportionately suffer. Approximately three quarters of homicide victims are of African descent, despite the fact that Africans make up only about 37% of T&T’s population.

It is not only the syndicates that profit. In fact, the illicit trade and efforts to combat it have fuelled widespread government corruption reportedly implicating senior government officials, members of law enforcement and the courts. Even a cursory glance through local newspapers over the last month reveals the profiteering and casualties attached to this ongoing saga. For example, a series of news reports in May document a number of different criminal activities involving the police, including the disappearance of cash and the discovery of large amounts of drugs and ammunition hidden in the roof of a police station. The Police Service Commission called for an investigation “concerned over what appears to be the continuing erosion of public trust and confidence in the Police Service.” Earlier this month, T&T Prime Minister Kamla Persad-Bissessar publicly responded to accusations that her administration had dismantled drug control initiatives launched by the previous administration, “because we wanted to increase the drug trade.”  She challenged this interpretation at the formal commissioning ceremony for two newly purchased Augusta Wesland AW139 helicopters which she explained would provide the technological sophistication necessary to ensure that “crime suppression is boosted.” In a move conforming to drug warfare across the region, the PM seems to embrace increased policing and militarization, outlining a new “border protection and naval operation plan” involving 12 new coastal guard stations, fast patrol boat interceptors, and the operations of a radar system to “ensure that the country will now be properly secured, or locked down.”

She challenged this interpretation at the formal commissioning ceremony for two newly purchased Augusta Wesland AW139 helicopters which she explained would provide the technological sophistication necessary to ensure that “crime suppression is boosted.” In a move conforming to drug warfare across the region, the PM seems to embrace increased policing and militarization, outlining a new “border protection and naval operation plan” involving 12 new coastal guard stations, fast patrol boat interceptors, and the operations of a radar system to “ensure that the country will now be properly secured, or locked down.”

As a final sampling, as I write this today the lead story across local papers is testimony delivered yesterday in an inquiry into the country’s 1990 failed coup attempt at hearings before the Caribbean Court of Justice in T&T’s capital Port of Spain. A member of Jamaat al Muslimeen, the organization which led the coup attempt, testified the coup was inspired by frustration with the then government’s apparent collusion or at least willingness to turn a blind eye to the drug trade. Jamal Shabazz testified that the killing of a police constable during a training exercise in 1987 had not been an accident, but rather was in retaliation for her having reported to the group that she witnessed three prominent government officials consuming and covering up the discovery of a large stash of cocaine. Shabazz acknowledged that the organization had turned to violent vigilante justice in its own efforts to shut down the trade, and reportedly suffered being targeted by the police as a consequence. The real story however is no doubt murkier. Jamaat al Muslimeen itself has been directly implicated in the illicit drug trade. Townsend goes so far as to describe the group as “a powerful criminal force” that is widely “alleged to be responsible for numerous extortions, drug-selling and smuggling operations, money laundering, and kidnappings.”

Disentangling legality, illegality, and legitimacy in this context is difficult—it is a situation which seems not dissimilar from that in Jamaica, where slightly more than a year ago the attempt to arrest and extradite to the United States prominent drug kingpin Christopher “Dudus” Coke led to a standoff between security forces and Coke’s supporters which resulted in almost a hundred deaths. Horace Campbell has eloquently written about the drug war in the Jamaican context. Coke, referred to as the ‘Pres’, was said to be more powerful than politicians (the PM in fact had initially protested the U.S. extradition request), even while his connections to them charts a story of deep-seated official corruption and complicity in the drug trade. Coke also had enormous influence in the community—whether it was the power to unleash political intimidation at election-time or the considerable popularity he held as one of the few providers of social services for people living in the community he controlled.

One way to look at the issue is as a problem rooted in the triumphant force of aggressive capitalism and the negative consequences this has had for the vast majority of the country’s and the entire Caribbean region’s population. The ascendancy of profit-motive as the preeminent force in global politics, embodied most dramatically in U.S. domestic and foreign policy, has empowered a rapacious form of capitalism—legal, illegal, and the shadowy world of the in-between—that undermines communities’ capacity to mobilize for genuine political reform, to promote human and economic security, and to protect health and safety, effectively trampling peoples’ basic human rights. The market does not discriminate between the legal and illegal when it comes to undermining the average citizens’ security and the possibilities for grassroots political mobilizations.