Over the past 30 years, the top 1% of the United States has experienced a 240% increase in its real annual income, while that of the median household has barely budged. Imagine if this explosive, decades-long growth of inequality were somehow reversed—and reversed at an even faster rate than its original expansion.

This is, in fact, what has happened in Venezuela, and it goes a long way toward explaining why President Hugo Chávez was re-elected in October, despite many pundits’ predictions of a victory by opposition leader Henrique Capriles. The likelihood of coming across an accurate assessment of Venezuela’s social and economic advances in the media, however, is about as small as the odds of encountering honest portrayals of that country’s elections.

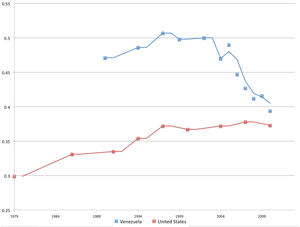

It’s difficult, for instance, to find any mention in the media of the Gini index for the United States or Venezuela. A standard measure of income inequality, it ranges from 0 (perfect equality) to 100 (perfect inequality). According to the Luxembourg Income Study, the Gini index for the United States was 29.9 in 1979. By 2010, it had shot up by more than 7 points to 37.3.

Contrast this with Venezuela: the country’s Gini index in 1997, the year before Chávez was elected, stood at 50.7; in 13 short years, it had fallen by over 11 points to 39.4, according to United Nations data for 2010.

This rapid reduction of inequality is largely a result of the Chávez administration’s policy of promoting broadly shared economic growth. Having cut both poverty and unemployment by half over roughly a decade, Venezuela is now the least unequal country in Latin America, according to the UN.

The poverty and inequality statistics are based only on cash income. But Chávez also introduced a suite of oil-financed social programs that provide free healthcare, education, housing, and subsidized food, among other benefits. Their effects include substantial reductions in infant mortality and the doubling of the country’s college enrollment.

Chávez’s social and economic agenda has also helped him to win 14 of 15 elections or referenda despite the inevitable voter fatigue that develops toward any incumbent over 14 years in office. On October 7, Chávez won by an 11-point margin in an election process described by Jimmy Carter as “the best in the world.” This suggests that for voters, continued advancements in well-being have outweighed ongoing problems like crime and inadequate infrastructure.

The paradigm that has emerged during Chávez’s presidency is threatening to the dominant political discourse in the United States for two related reasons. First, it demonstrates that poverty and inequality, far from being implacable economic phenomena, are primarily political issues, and can be successfully tackled through aggressive public policy. Second, a governmental commitment to improving the general public’s living standards engenders a new kind of politics, distinct from the consensus that prevails under a decades-old regime of ever-increasing economic polarization.

Elite policy circles in the United States have agreed that austerity is necessary: both major parties’ presidential candidates suggested the need to institute cuts to an already-weak social safety net. Unemployment, in Bill Clinton’s incorrect rendering, lies outside the purview of immediate government efforts to spur greater demand. Federal Reserve chair Ben Bernanke attributed inequality, which has concentrated income within the top 1% and even more so within the top .01%, mostly to “educational differences.” He ignores Princeton economist Paul Krugman’s observation: namely, “that we’ve become an oligarchy—with all that implies about class relations.” Bernanke’s statement also conforms with economist Dean Baker’s dismal assessment that most in his profession “are paid for telling stories that justify giving more money to rich people.”

The press, in turn, adheres closely to elite opinion. Establishment media have abetted efforts to scale back the anti-poverty program Social Security, while meaningful discussions of poverty comprised a fraction of 1% of the media’s campaign coverage. The reason is easy to see. Baker writes, “while Social Security may enjoy overwhelming support across the political spectrum, it does not poll nearly as well among the wealthy people—who finance political campaigns and own major news outlets.”

While experts in the United States warn that banks have engaged in widespread illegal foreclosures, exacerbating housing insecurity, the U.S. media have disparaged Venezuela’s public housing initiatives as an unsavory political scheme. David Frum, former speechwriter for George W. Bush, wrote an op-ed for CNN titled, “Chavez Clown Prince of a Decaying Society,” decrying “massive government vote-buying” through “giveaway programs, including one that aims to build 200,000 housing units for Venezuela's poor.” The Wall Street Journal’s reporting similarly criticized Venezuela’s housing construction, citing unnamed analysts who wondered “whether the spending spree will buy as many votes this time around as in past elections.”

USA Today’s coverage of Venezuela’s elections included quotes by critics who condemned Chávez’s “patronage machine,” which “unleashed a spending orgy.” The paper also dutifully noted that Capriles considered “new social spending” to be “vote buying.”

Rarely is the U.S. political system similarly condemned as a patronage machine, despite each major presidential candidate securing $1 billion for his campaign, often through $35,000-a-ticket fundraising dinners with corporate executives. Research has also shown that nearly half of all federal lawmakers become lobbyists after returning to private life. Little wonder Princeton political scientist Martin Gilens’s research finds that “in most circumstances, affluent Americans exert substantial influence over the policies adopted by the federal government, and less well off Americans exert virtually none.”

Interestingly, USA Today’s post-election breakdown for Venezuela failed to mention its historic, 81% participation rate. Such a turnout would be unimaginable within the United States, even leaving aside vigorous efforts of voter suppression all over the country. In an earlier article headlined “Why 90 million Americans Won't Vote in November,” USA Today itself offered a reason: it found that six in 10 eligible but unlikely voters said, when surveyed, that they “don’t pay much attention” to politics because “nothing ever gets done: It’s a bunch of empty promises.”

The era that preceded Chávez’s 1998 election has echoes of the current predicament of U.S. politics—two major parties with fairly similar agendas took turns managing the country’s governmental institutions while elites controlled the country’s resources. Venezuela’s democracy, like much of Latin America’s, has meant a break with that past.

The U.S. press helps to enforce the status quo in a country whose majority has faced declining living standards in recent years, largely as a result of policies furthered by a bipartisan political system. So it’s not surprising to see the U.S. media’s hostile reactions to the politics of Venezuela, where citizens expect their votes to translate into genuine improvements in their daily lives—and politicians must deliver on those expectations.

A version of this piece will appear in the December issue of Extra!, a publication of the media watchgroup FAIR.

Keane Bhatt is an activist in Washington, D.C. He has worked in the United States and Latin America on a variety of campaigns related to community development and social justice. His analyses and opinions have appeared in a range of outlets, including NPR, The Nation, The St. Petersburg Times and CNN En Español. He is the author of the NACLA blog “Manufacturing Contempt,” which critically analyzes the U.S. press and its portrayal of the hemisphere. Follow his blog on Twitter @KeaneBhatt.