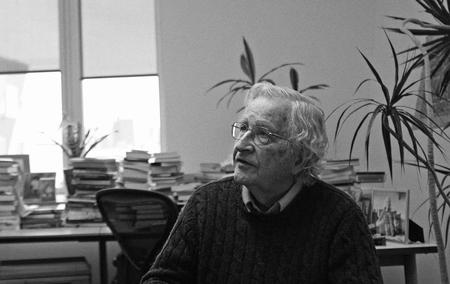

[Renowned linguist, political analyst and activist Noam Chomsky offered his thoughts to me on Latin America and the role of the United States last month. Among his many observations, he considered Honduras as "a kind of a horror story," and Haiti "an NGO dependency." The following is an excerpt from a longform interview available at Truthout.org.]

Keane Bhatt: While human rights organizations provide valuable information and engage in important advocacy, they can play a role similar to that of The New York Times, demarcating what qualifies as respectable debate. José Miguel Vivanco, director of Human Rights Watch's (HRW) Americas division, singled out Venezuela by saying a 2008 report was written "to show to the world that Venezuela is not a model for anyone." He and HRW's global advocacy director Peggy Hicks wrote a letter to Chávez on November 9, saying that the country was unfit to serve on the UN's human rights council, which The Washington Post repurposed as an editorial two days later. HRW sent no similar letter to Obama, and the United States was quietly re-elected to a three-year term on the same council.

Amnesty International, for its part, went to Chicago for the NATO summit in May, but unlike activists protesting the brutal U.S. military occupation of Afghanistan, Amnesty's Cristina Finch wrote that, "There is real danger that women's rights will get thrown under the bus as the United States searches for a quick exit from Afghanistan . . . This is a defining moment for the U.S. government to show that it will not abandon women."

Carlos Lauría of the Committee to Protect Journalists called his organization a "human rights defender," yet said little to defend beleaguered journalist Julian Assange of WikiLeaks, who faces the threat of extradition to the United States, where he could be held under the same "cruel, degrading and inhuman" conditions that Bradley Manning suffered. Instead, Lauría noted that it was "ironic" that Ecuador "has granted asylum to Assange," given the country's poor reputation on press freedoms. No watchdog groups noted the irony of Ecuadorian editor Emilio Palacio seeking asylum within the United States, which imprisoned an Al Jazeera cameraman for six years in Guantánamo.

Having detailed the behavior of the media, do you think such institutions similarly manufacture consent? And given their sterling reputations in the public sphere, is there a way to hold these accountability groups accountable?

Noam Chomsky: They do some good things. They're part of the educated, liberal, intellectual elite and suffer from its deficiencies; so you hold them accountable in the same way you hold the media and intellectual community accountable. Take Human Rights Watch. There's some things that they've proposed that they keep kind of quiet, but which are quite good. They're way out in the lead in boycotts, divestment, and sanctions on Israel. They've called on the U.S. government to stop any funding of Israel that's in any way related to the occupied territories or to repression inside Israel. That's nice. It's a good plank—they make sure no one hears much about it, but I'm glad it's there.

Venezuela is one of their main hates, so they'll say Venezuela is not fit, but they won't say the United States is not fit, though it's much worse than Venezuela. You can say the same about the press. You can say the same about the Harvard Faculty Club. These are the things you have to struggle against all the time.

KB: You've described Latin America as a region that gives you hope for the future. However, over the last few years, two democratically elected reformist governments have been overthrown in what are being termed parliamentary coups: Manuel Zelaya of Honduras in 2009 and Fernando Lugo of Paraguay in June. Do you see these as isolated incidents or as part of a larger trend?

NC: The coup in Honduras is one act, and the overthrow of Lugo is another. The effort to reestablish military bases in Chile is yet another. They're all part of the same thing. Latin America has extricated itself to a very large extent from Western control. The U.S. military bases have been thrown out. During the hemispheric Cartagena conference, the United States and Canada were totally isolated. The United States is not giving up—it's trying to reconstruct its position. Honduras is a striking case—that's Obama. But they're going to keep trying. If they succeed depends in part on Latin American resistance and in large part on us.

KB: In the 60s and 70s, the United States helped initiate and fortify dictatorships in some of Latin America's most powerful countries, like Brazil, Chile, and Argentina. Is it a (grim) sign of progress that the only cases in which the United States was successful in subverting democracy recently were Honduras in 2009 and Haiti in 2004 and 2010? They happen to be the hemisphere's poorest and most vulnerable countries.

NC: Haiti and Honduras are indeed the poorest and most vulnerable, and incidentally there's a quite good correlation between U.S. intervention over many years, and poverty and destruction. So for example, if you look at Central America and the Caribbean, the main area of U.S. intervention, the poorest country is Haiti, the leading target of U.S. intervention. Vying for second place are Guatemala and Nicaragua, and Honduras is sort of hovering around there too; they are the next main targets of intervention.

If you go on, the United States hasn't overthrown the government or invaded one country, which is Costa Rica, and it's the one that's more or less functioning. Also, Honduras is very important because it has a major U.S. military base. As you know, the United States has been expelled from all of its military bases in South America. It's trying to reconstitute some, but right now it doesn't have any solid ones. The Palmerola base in Honduras is a major U.S. base, and I presume that has something to do with U.S. support for the election which took place under the coup regime, effectively support for the military coup. Also, Zelaya was moving somewhat tentatively towards the kinds of social reforms that the United States has always opposed and will try to stop if it can—and it's presumably another reason.

As for Haiti, that's just been the plaything of the imperial powers—mainly France and the United States—for hundreds of years. It's kind of interesting the way it's described. So, for example, The New York Times recently had an article on how Haiti has been harmed by poorly conceived agricultural policies, as for example, reliance on highly subsidized U.S. rice exports since the mid 90s. But they failed to add that; acceptance of these highly subsidized rice exports was, of course, a condition that Aristide had to accept in order to be reinstated in Clinton's intervention in 1994. And that was done with the certain knowledge that it would undermine Haiti's rice production.

In fact, USAID studies and others have pointed it out, but it's obvious anyway. Years later, Clinton said, "I'm sorry, I didn't realize it," which you can believe if you'd like. But that's the slight omission of guilt, and in fact it goes well beyond, because Clinton had imposed conditions that required Haiti to open its borders to all kinds of foreign economic intervention, and, in fact, some of it is kind of grotesque.

So, for example, Haiti's a very poor country and doesn't have much to sustain it—especially after years of U.S. policies and more, going back, but it did have a couple of things functioning. Actually, it did have pretty good agricultural production (like rice, but that was wiped out). It had, for example, a small chicken-parts factory.

Well, major American producers like Tyson have a lot of extra dark meat around because Americans don't like dark meat, so they're trying to dump them on the market. Canada and Mexico are independent enough that they can block it with anti-dumping procedures, but Haiti, thanks to Clinton's rules, couldn't, so that small industry was wiped out by huge American food processing companies like Tyson. And it continues.

KB: You once said Clinton's apology for decimating the country's agricultural base may have been unprecedented in imperial history. Yet last month, flanked by celebrities, the Clintons inaugurated a garment factory sited on rich agricultural land, which was donated to the company by the Haitian government after its farmers were displaced. The Inter-American Development Bank and the United States paid for much of the infrastructure. What will be the contours of this kind of development for the country?

NC: More destruction of Haiti—and incidentally, I didn't really take Clinton's apology very seriously. I mean, it's inconceivable that he didn't know what he was doing when he imposed those conditions on the restoration of Aristide. There's more to it than that. So for example, I haven't heard Clinton apologize yet for the fact that under the military coup regime—a regime of real terror—there's one thing that the Haitian elite and the military junta needed: oil. And while the CIA was testifying to Congress that all oil shipments had been stopped, you could see in fact—I was there—the oil farms being built by the rich families. And it turned out that Clinton had quietly authorized the Texaco Oil Company to evade the presidential directive against sending oil to a military junta. I haven't seen the apology for that one yet.

KB: Following the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, I asked you whether physician Paul Farmer of Harvard, who represented a just development model, could influence the UN as Clinton's deputy envoy. You said you didn't blame him for trying, and that sometimes it's necessary to follow painful paths if we hope to provide at least a little help for suffering people. Over the past three years, what have been some of the benefits and trade-offs of his participation, and do you see any lessons to take away?

NC: Well, I still would say essentially that. I think he knows what he's doing, and I trust his judgment and his integrity—Paul Farmer that is, I'm not talking about Clinton [laughs]. There have been a few things, and some Haitians have been helped a little bit, but the general impact has been to turn Haiti into what's sometimes been called an NGO dependency.

I think only half of the promised aid ever got there. A lot of it is sitting in various accounts somewhere, not dispersed. What is dispersed is under the control of external sources: the NGOs and governments. The Haitians are pretty much kept out of it. The Haitian government is kept out, but more significantly, the Haitian civil society movements—which are quite important and active—they're very largely kept out.

And what's developed is something that meets the interests of sponsors and may have little or no value; it may even be of harm in the long term to the Haitians. Now there's one striking exception to that, and that's Paul Farmer's organization, Partners In Health. They've been there doing the same kind of work they've been doing for years: trying to create health programs and institutions and structures that can be taken over by Haitians, and in fact have been, in some significant cases. They're responding to the initiatives and concerns of the Haitians. That's the right thing to do, and I'm sure there are some others. I haven't studied it in detail, but I don't think it's the general pattern.

KB: In late September at Georgetown University, Argentina's President Kirchner spoke with pride about her country's involvement in the UN military occupation of Haiti, which was organized by the United States after it orchestrated a coup in 2004. Why did Latin America's left-of-center governments sign on to this mission? Why was there no protest from Brazil, Uruguay, or Argentina over the Organization of American States' (OAS) intervention in Haiti's already-fraudulent election in 2010? What would you recommend as appropriate steps forward for left-leaning Latin American countries regarding Haiti?

NC: Brazil had the leading role. I was kind of surprised at that, frankly, particularly when the harmful effects of the MINUSTAH [the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti] operation have become more and more clear. I don't know what motivated Brazilian policy. My suspicion is that it's part of their effort to gain some international recognition as part of their efforts to gain a permanent position on the UN Security Council, but that's just a speculation.

I don't think it's an honorable policy—same with Argentina. And I think everyone—progressives in particular—should be trying to organize public understanding of what the impact has been and to try and press for more constructive policies, which, at this point, would probably mean withdrawing the foreign intervention forces. I believe, as far as I know, that's what most of the Haitian people want, and they're the ones who should make that decision, not me.

KB: The UN occupation is now almost nine years old. Its troops' negligence led to the introduction of cholera, which has killed more than 7,500 people, and the UN is silent as to whether it will provide reparations to its victims. Haiti needs $2 billion over ten years to eradicate cholera, but that plan is unfunded. Meanwhile, the UN will spend $2 billion over the next three years on the military occupation. Yet there's a general aversion (outside the far right) to criticize the UN.

NC: Well, first of all, what the UN does is very tightly constrained by the great powers and particularly the United States. It can't go much beyond the bounds that they set. In addition, the UN has plenty of internal incompetence and corruption, but I tend personally not to place so much of the blame on the UN, even though there's plenty of problems there, but on its masters: namely, the Security Council and the United States.

I think your question, "Why isn't the money spent for dealing with the epidemic that the UN troops created and could solve," is part of the general question: Why are there no sustainable development projects responding to the initiatives and the needs of the Haitian people? The whole international effort—not all of it, like, not Partners in Health and a few others—is basically determined by the interests of the external agents who want to dominate and control and are not responsive to popular needs and interests, not just in Haiti, but quite generally. In fact, even domestically—like the question of the deficit that I mentioned earlier. Why the disparity? Well, you look at the power structures behind it—the financial institutions—and you get answers.

KB: Let's go back to another of Clinton's apologies: in 1999, he expressed public regret over U.S. military and diplomatic support for Guatemala's genocidal policies, which likely killed hundreds of thousands. He said the United States must not repeat that mistake. Today, the United States provides $50 million in annual funding to Honduras's brutal security apparatus; U.S. agents have personally participated in raids that have killed civilians; Honduran troops accused of atrocities have been trained at the School of the Americas in Georgia and vetted by the United States. With the creation of new military bases there, do you see the United States opening a new chapter of Reagan-style support for death-squad governance?

NC: Well, as you indicated, it's not a new policy. That's been the policy for decades, and where there are opportunities, that's pretty much what the United States has been doing. And it's perfectly true that since the military coup and the establishment of the Lobo government under the coup regime, which Obama supported (he was almost alone on that internationally), Honduras has become a kind of a horror story. It has the worst record of violence in the hemisphere—one of the worst in the world. It's a significant development; in fact, it's been harmful all around. And yes, it's another support for, if you'd like, a death-squad government. That's traditional U.S. policy—nothing to be surprised about.

KB: Are large actions like the recent protest at Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC), formerly the School of the Americas, an indication of more citizen engagement on such issues, given that the scope of today's crimes is smaller than that of the 1980s?

NC: Regarding the protests, yes, sure, they ought to take place. But the protests require, first, educational efforts so people understand what they're about. I suspect if you did a poll in the United States, only a fraction of the population would even know where Honduras is.

KB: Shortly after Obama's reelection, the United States launched a drone bombing in Yemen; the United States, along with Israel and Palau, opposed 188 UN member states' resolution to end the illegal embargo on Cuba; and the administration participated in Israel's aerial bombardment of Gaza by providing diplomatic support and weapons. Many had hopes for a more progressive second term, but what are the prospects that the Obama administration will have simply a more moderated second term, like that of George W. Bush?

NC: I don't even think it will be more moderated. Bush was so extreme in his first term with the crazy rhetoric and aggression that he just had to pull back. But Obama doesn't have those pressures. In fact, I think there's something like what you said, but more significant.

Take a look at the last presidential debate on foreign policy. Two words dominated everything else: Israel— because you have to show how much you adore and worship it—and Iran, because it's the greatest threat to peace in the world. Well, let's take the second part, Iran being the greatest threat to peace.

There are some questions: first of all, who thinks that? Turns out it's the United States and some of Europe, but not even the European public, which in polls regards Israel as the greatest threat to peace. So it's the United States leadership, and some of its allies who think it's a threat. It's not the nonaligned countries; it's not the Arab world—some of the Arab dictators, but not the population.

The next question is, what's the threat? Well, the threat is deterrence. Iran might prevent the United States from exercising force freely, which cannot be tolerated. The third and most interesting question is, what can you do about it? Suppose you think it's a threat. What can you do to mitigate the likelihood that Iran will develop nuclear weapons? There's a very simple method: move towards establishing a nuclear-weapons-free zone, which everybody in the world wants, but the United States blocks.

There is a perfectly good way to proceed, there's a Helsinki conference coming up. The only way the United States could stop blocking it is if there's popular pressure. There can't be popular pressure unless people know what's happening. They can't know what's happening because the free press, with 100% conformity, literally, has refused to report it. That's the problem. That means continued threats of war.

KB: Finally, the World Trade Organization's Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights agreement, as well as NAFTA, were organized to an astonishing degree by corporate lobbies. International agreements are even more opaque and shielded from scrutiny than national policies; they're not routinely published in draft form or publicly debated, and citizens often learn of such global rule-making only after it's been finalized and adopted. Today, little-known rule designing like the Trans-Pacific Partnership and drug patent laws can have an enormous impact on millions of lives. Are there specific methods for regular people to influence supranational policies, given that they're so far-removed?

NC: They're the kind of tactics that activists used, including the labor movement, in vain, unfortunately, in the case of NAFTA and the WTO. So take, say, NAFTA: the executive version of NAFTA was rammed through without public debate, and in fact, public input was pretty much barred. U.S. trade acts require government consultation with the labor movement before instituting agreements like that, but the labor movement was not even notified officially until barely before the Congressional vote. It nevertheless produced a major document, by the Labor Action Committee, giving a critical analysis of the executive version of NAFTA, predicting, correctly as it turned out, that it would lead to a low-wage, low-growth economy for all three participant countries, and suggesting alternatives that could very well lead to a high-growth, high-wage alternative.

The Labor Action Committee proposals happened to be virtually identical to those proposed by Congress's main research bureau, the Office of Technology Assistance, which has since been disbanded. I think neither of them even got a notice in the media, so they were cut out. Some people wrote about them—I wrote about them, and others—and activists tried to break through this, but it was blocked.

And that just means you need more organization, more education, and more activism.

Keane Bhatt is an activist in Washington, D.C. He has worked in the United States and Latin America on a variety of campaigns related to community development and social justice. His analyses and opinions have appeared in a range of outlets, including NPR The Nation, The St. Petersburg Times and CNN En Español. He is the author of the NACLA blog “Manufacturing Contempt,” which critically analyzes the U.S. press and its portrayal of the hemisphere. Follow his blog on Twitter @KeaneBhatt