Due to the decline of the traditional sugar and banana exporting industries, many cash strapped Caribbean islands have been resorting to an unusual and controversial method to raise revenue—selling citizenship.

While economic citizenship programs already exist in Austria, Bulgaria, Britain, and Canada, they often take several years for the applications to be processed—while in the Caribbean it only takes a couple of months. While no specifics on the nationalities involved have been released, it has been widely circulated that those most interested in the economic citizenship program are primarily the wealthy from China and the Arab World.

Armand Arton, of Arton Capital, a financial advisory business based in Montreal specializing in immigrant investment programs, remarked that his firm “had provided advice to more than 500 families in 2011 and that 75% of them had been from the Middle East.”

Since September 11, there has been a crackdown on granting visas to individuals from Arab/Muslim countries, and as such Caribbean citizenship provides a way to avoid the travel restrictions. Furthermore, the political instability in Iran, Syria, and Egypt has provided an incentive for individuals to secure a second passport in order to access a distant safe haven such as St. Kitts and Dominica.

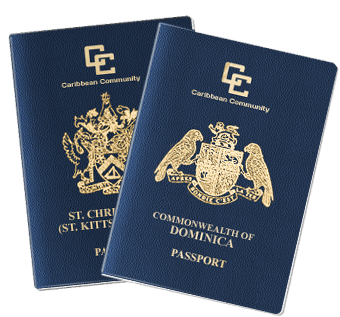

The Government of St. Kitts states that its economic citizenship program is open to “Investors of good character and repute” and that the program “facilitates you and your family's ease of travel throughout the world to over 100 countries visa free. Holding St. Kitts & Nevis citizenship also gives expansion on your business opportunities without being taxed on worldwide income.”

In St. Kitts and Nevis, citizenship can be obtained through two different methods. The first involves a minimum “non-refundable donation” of US$250,000 by a single individual to the Sugar Industry Diversification Fund (with an additional US$7,500 in government fees). The second way to obtain citizenship is through a minimum real estate investment of US$400,000, which is subject to associated taxes and fees.

However, this process is also evolving into more than just a straight forward cash for citizenship transaction and is now being folded into development projects. This summer, the Dubai based Range Developments announced plans to construct a luxury Park Hyatt hotel in St Kitts & Nevis. The developer has offered investors spending more than $400,000 to apply for citizenship of St. Kitts.

Munaf Ali, CEO of Range Developments, remarked that “Investing in the Park Hyatt hotel project will entitle you and your family to apply for citizenship of St Kitts & Nevis. This opportunity provides second citizenship to eligible individuals in 90 days and opens visa-free travel to more than 139 countries across the world.”

In Dominica, the fee for their program is $100,000—taking between five to nine months. Unlike St. Kitts, the process requires that applicants speak English and visit the island for an interview. It was estimated that in 2012 alone, approximately 1,500 people have applied for the citizenship investment program in St. Kitts and Nevis and 500 for Dominica. Dominica’s citizenship program has been less popular than St. Kitts due to the fact that there were travel restrictions concerning the countries of the European Union. However, that restriction is now in the process of being lifted, and Dominica should soon see an increase in the number of citizenship applicants.

Most recently, Antigua has joined St. Kitts and Dominica seeking to gain revenue off of granting citizenship to foreign nationals. That said, the country is also worried about the darker side of implementing an economic citizenship program—specifically in regards to whether the actions of the new citizens will jeopardize the freedom of movement for Antiguan born citizens. In the Jamaica Gleaner, David Jessop called for tight monitoring and regulation of the citizenship programs, as poorly enforced programs could lead to a rise in criminal activity or worse.

The lack of transparency of these programs has been noted domestically, as Dwyer Astaphan, St. Kitts former Minister of National Security, Justice, and Legal Affairs, remarked that that former sugar industry workers, intended to be the beneficiaries of the sugar fund, have no way of knowing where the money goes. Astaphan stated that “There's no transparency. Imagine making a contribution to a foundation to get citizenship of a country, but the inside information of the foundation is kept secret!”

Crispin Gregoire, Dominica's former ambassador to the United Nations has remarked that "I am not a fan of the economic citizenship program... As it stands, it encourages people with something to hide. I understand that it must be a big source of income for the state, but they're not doing a good job of regulating it."

Additionally, such programs highlight the inequality in resources between the new citizens of these Caribbean islands and the traditional population. It reveals the extent to which these economically vulnerable countries will go to gain much needed revenue sources. Due to their wealth, those with new citizenship have access to travel and investment opportunities which are out of the reach of the average Caribbean citizen. Without any transparency and regulation, the benefit to the populations of these Caribbean countries is outweighed by the possibility of losing their freedom of movement to countries which are home to large Caribbean diasaporas such as Britain, Canada and the United States.

The economic citizenship programs also provide a direct stream of income which could be captured by political parties if regulation and transparency is not adopted and made available to the public. While the popularity of these programs are still fairly new, there is no reason not to call upon the governments to immediately show where the money is being directed—as they now constitute important, albeit controversial, sources of revenue.

Kevin Edmonds is a NACLA blogger focusing on the Caribbean. For more from his blog, "The Other Side of Paradise," visit nacla.org/blog/other-side-paradise. Edmonds is a former NACLA research associate and a current PhD student at the University of Toronto, where he is studying the impact of neoliberalism on the St. Lucian banana trade. Follow him on twitter @kevin_edmonds.