On Tuesday, July 31, the presidents of Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay met in Brasília and formally admitted Venezuela into Mercosur, the world’s third-largest trading bloc. Venezuela’s full membership, the BBC reported, had been previously approved by all of Mercosur’s member countries except Paraguay, whose rightwing congress had obstructed the initiative for years. With Mercosur’s recent suspension of Paraguay over a parliamentary coup carried out in June, which saw Paraguay’s President Fernando Lugo overthrown, the $3 trillion trade grouping easily voted Venezuela in.

Cristina Kirchner of Argentina called July 31 “a historic day” that would herald the rise of Mercosur as a “new pole of world power.” Brazil’s Dilma Rousseff said “Venezuela's entry increases the potential of the bloc, giving it greater geopolitical and global economic dimensions.”

Simon Romero, however, writing for The New York Times, portrayed Venezuela’s entry as a cause for concern. In fact, he provided the final word of his piece to a political scientist who believes Venezuela’s admittance “sets a terrible example for the region” and “reveals Mercosur’s political weakness.” Romero is not alone in underlining the supposedly troubling aspects of this unprecedented step toward regional integration—The Economist called the move “cunning,” and Businessweek began its article on the subject by contending that “Hugo Chavez’s back-door entry” somehow “casts doubt on the future” of Mercosur.

This characterization is misleading. Members of Mercosur decided to suspend Paraguay’s membership on wholly legitimate grounds: On June 22, Paraguay’s congress impeached the democratically elected president, Lugo, in violation of Article 17 of Paraguay’s constitution, which guarantees the right to due process. Congress gave Lugo just one day to prepare a defense, and allotted his legal team only two hours to defend him. Following the illegal ouster of Lugo, President Cristina Kirchner of Argentina said Mercosur’s leaders should not “tolerate these ‘gentle coups’ or movements that—under a veneer of institutional correctness—shatter the constitutional order.”

Nevertheless, in Romero’s version of Mercosur’s July 31 inclusion of Venezuela, the three other member countries had somehow performed an “outmaneuvering of the Paraguayan Senate”—even though the countries had previously suspended Paraguay for overthrowing its elected leader. He also doesn’t explain how Venezuela’s formal entrance to Mercosur had been “stalled by resistance in some member nations” when he writes in the subsequent paragraph that “Brazil, drawing support from Argentina and Uruguay”—that is to say, all of the remaining participants in Mercosur—“moved swiftly to formalize Venezuela’s membership.”

Furthermore, Romero ignores Argentina’s key role in suspending Paraguay after the coup and its vigorous support for Venezuela’s membership in Mercosur. He instead frames Venezuela’s inclusion as the result of Brazil’s self-interested maneuvering, for which it was rewarded handsomely through Chávez’s purchases of Brazilian passenger jets. According to Romero, Brazil’s hypocrisy is evident to critics of Chávez: “They say Brazil is ignoring reports of Mr. Chávez’s concentration of power and the erosion of judicial independence in Venezuela while it expresses concern over Paraguayan democracy.”

Romero gives such criticisms ample space; he even dedicates a paragraph to Chávez’s tardiness and deviation from protocol at Mercosur’s accession ceremony. In contrast, Romero does not once explain the background behind the antidemocratic ouster of Paraguay’s Lugo, which happens to be a principal reason behind Venezuela’s inclusion.

Romero has previously demonstrated a tendency of downplaying the threat to democracy that Lugo’s unconstitutional removal poses. In his June 23 article on Lugo’s overthrow—misleadingly titled, “In Paraguay, Democracy’s All-Too-Speedy Trial”—he allowed Michael Shifter, president of the Washington, D.C.-based Inter-American Dialogue, to incorrectly state that Paraguay’s “Congress may have acted in accordance with the Constitution” when impeaching Lugo. Romero also quoted Paraguayan law professor Alberto Poletti, who ignored Lugo’s right to due process: “The process in which Lugo was removed may not have looked fair, but it was entirely legal,” he said.

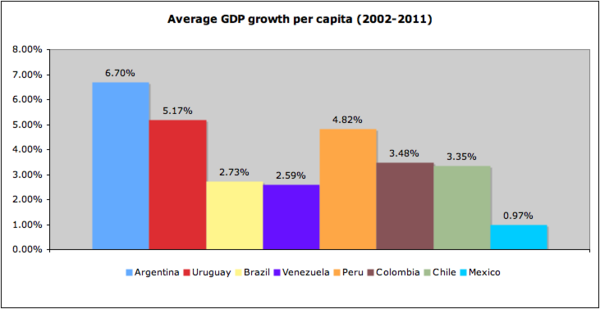

Lastly, in attempting to illustrate the fraught nature of Mercosur, Romero argues that the organization is “grappling” with “the rise of another regional bloc, the Pacific Alliance, whose four members—Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru—have enjoyed fast economic growth.” One may suspect that Romero’s description of a trade grouping made up of four historically conservative Latin American governments is too convenient. And it is. The International Monetary Fund’s statistics beg the question: How could anyone reasonably argue that Mexico has “enjoyed fast economic growth” when its per capita GDP has increased at under 1% for a decade?

Source: International Monetary Fund

Keane Bhatt is an activist in Washington, D.C. He has worked in the United States and Latin America on a variety of campaigns related to community development and social justice. His analyses and opinions have appeared in a range of outlets, including NPR, The Nation, The St. Petersburg Times, CNN En Español, Truthout, and Upside Down World. He is the author of the new NACLA blog “Manufacturing Contempt,” which takes a critical look at the U.S. press and its portrayal of the hemisphere.