Originally posted at forusa.org on November 5, 2013

Once the signature program of the U.S. drug war in Latin America, aerial fumigation of coca leaf crops is finally in deep trouble.

Fumigation’s crisis comes in a moment when coca growers, like other farmers throughout Colombia, face an economic crisis that led to a month-long national agricultural strike in August.

Colombia recognized the environmental, economic, and health damages of aerial fumigation in September, when it agreed to pay $15 million to Ecuador to settle a demand the neighboring country made at the International Court of Justice, based on destruction caused by aerial spraying in border areas. Ecuador’s lawsuit cited academic studies and regulatory warnings about the health risks of fumigation with glyphosate, studies ignored by the Colombian government.

The settlement requires Colombia to refrain from fumigating within 10 kilometers of the Ecuador border—an agreement made in 2006 and violated by Colombia. It also commits Colombia to give advance notice to local officials of border-area fumigation, to spray only in daytime, and to periodically evaluate impacts on human and livestock health, the environment, and displacement.

But the settlement highlights the risks to exposed communities and ecologies brought by continued aerial spraying inside Colombia, which are not addressed by Ecuador’s demand. Colombia makes no commitments to its own communities such as those required for Ecuador.

Virginia-based Dyncorp continues to spray some 100,000 hectares annually in Colombia, particularly in the southern states of Nariño and Putumayo. The protocols reportedly regulating such fumigation are secret.

Meanwhile, a commission appointed by President Juan Manuel Santos to study drug policy issued a report highly critical of aerial fumigation, not only for its negative health and environmental effects, but for minimal effectiveness. The study found that for every hectare sprayed with glyphosate, coca crops were eradicated on only 12%-15% of the sprayed area, requiring fumigating the land nine times to achieve an effective reduction. Aerial spraying has also led to increased skin and respiratory problems in rural Colombian communities.

Santos’ foreign ministry responded to the report by trying to suppress its publication until well after the Ecuador lawsuit was settled, leading commission chairman, Brown University professor Daniel Mejia, to submit his resignation and publicly denounce the government’s actions.

Glyphosate also came under heavy criticism for negative health effects in Argentina. Associated Press reported on October 20 that Argentines living near the country’s booming soybean fields face elevated rates of cancer and birth defects after agricultural chemicals have been sprayed near them, often in ways against national law or scientific recommendations.

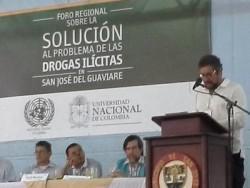

Two important fora convoked out of the peace talks in Havana between the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the Colombian government also addressed drug policy in October. At both gatherings in Bogotá and in the southern state of Guaviare, the strongest applause responded to calls for an end to fumigation and forced eradication of coca crops.

Adam Isacson, an analyst of the Washington Office on Latin America who spoke in Bogotá, pointed out that aerial fumigation was rationalized in the 1990s because the risks from armed groups to manual eradicators in coca-growing areas was too great, but that a peace agreement would eliminate that argument. He also noted that manual eradication, in the absence of markets, infrastructure, or state support, has adverse effects on both rural communities and their relationship to the State.

In further bad news for the drug war in Colombia, a U.S.-contracted aircraft monitoring drug trafficking routes crashed into northern Colombia on October 5, killing three U.S. citizens and a Panamanian on board. Two other contractors were injured in the crash, which was reportedly caused by human or mechanical error, not shot down by an armed group.

The United Nations-sponsored fora on illicit drugs concluded in Guaviare with a stirring statement read by National University sociologist Carlos Medina. Referring to the hundreds of rural people from the region who participated in the forum, Medina said:

“They want the State to return their children, their relatives, their neighbors, their wives, confined in ignominious prisons, treated not as peasants, indigenous or Afro-descendants, as human beings, but as criminals and delinquents for seeking to survive in a world without opportunities. They want the return of their families, planting cocoa, rubber, aloe, yucca, bananas, rice, rounding up cattle, milking cows, harvesting life and hope. They want them at their side to build bridges and paths to development and well-being. They want the money used for glyphosate in fumigation and forced eradication made into schools, health clinics, productive projects, life plans.”

As the forum in Guaviare dispersed, the question remained: Will Colombian and U.S. officials heed the appeals of peasants, the hard math of prices, and the conclusions of scholars, calling for an end to the failed project of coca fumigation and forced eradication?

John Lindsay-Poland is research director and western regional coordinator of the Fellowship of Reconciliation. He is the author of many articles on the U.S. military and human rights in Latin America, as well as Emperors in the Jungle: The Hidden History of the U.S. in Panama (Duke).