On September 25, Bolivians marked the second anniversary of events at Chaparina, where national police brutally repressed indigenous marchers protesting the construction of a government-proposed highway through the TIPNIS indigenous territory and national park.

At least 70 protesters were wounded during the intervention and four high-level government officials resigned. The episode marked a low point in the protracted (and still unresolved) TIPNIS conflict, and a rupture in the relationship between President Evo Morales and the lowland indigenous movement that helped bring him to power in 2005. For many inside and outside Bolivia, it called into question Morales’s status as a global champion of indigenous rights.

Two years later, the wounds of Chaparina are far from healed. The official investigation of the incident has been marred by confusion, a lack of transparency, and delays even more extreme than is typical for Bolivia’s over-burdened judicial system. The central question—who gave the order for the intervention?—has not been answered.

Morales has consistently denied responsibility for the episode, blaming unidentified rogue police for breaking the “chain of command.” Immediately after the incident, in a public plea for forgiveness, he cited his own experience as a cocalero union leader victimized by police repression during Bolivia’s “drug wars” as proof that he could never have ordered the attack. In a recent statement filed with investigators, Morales affirmed that no member of his cabinet was responsible for the intervention, and that learning about it “after the fact,” he did everything possible to safeguard protesters' rights.

Critics say the official narrative is contradicted by seeming evidence of executive branch involvement in purchasing supplies (such as adhesive tape) used during the attack, and in arranging for the buses, trucks, and military planes to transport the detainees. Former Defense Minister Cecilia Chacón (who resigned in protest after the incident) has testified that Morales, Vice President Alvaro García Linera, and other cabinet members monitored events at Chaparina as they occurred. Garcia Linera has also created confusion by stating that the government knows, but cannot reveal, who was responsible for the attack.

According to former Deputy Police Commander Oscar Muñoz—the only person detained to date in relation to the incident, who is currently under house arrest—the intervention order originated with then-Minister of Government Sacha Llorenti. This version of events is confirmed by Boris Villegas, a former government functionary currently imprisoned for extortion, and Edwin Foronda, ex-Inspector General of Police.

Early on, federal prosecutors excluded Llorenti (as well as Morales and García Linera) from the investigation, a decision which has become a flashpoint in the current controversy. Last month, lowland indigenous leaders filed a petition with more than 5,000 signatures, demanding that Llorenti be included in the case. A formal request to this effect has been pending for more than a year. “If he didn’t give the order,” says ex-Vice Minister of Interior Gustavo Torrico, “he’s still responsible for not being able to control the police, who were under his authority.”

Reflecting on the occasion of the anniversary, other former Morales supporters have been less judicious in their criticism of how the case has been handled. “The ‘government of change,’ by refusing to reveal names of those materially and intellectually responsible for the repression, is acting like the worst of the traditional neoliberal regimes," says Alex Contreras, Morales’s former press secretary. Contreras notes that several of the probable offenders have subsequently been rewarded with high level positions—including Llorenti, who is now Bolivia’s UN ambassador.

Anthropologist Xavier Albó likens the intervention at Chaparina to another shameful episode in Bolivian history: the brutal repression in 1985 of the March for Life sponsored by “relocalized” miners. By deliberately seeking to dismantle a peaceful protest and then covering up its actions, he argues, the Morales government has lost both internal and external credibility.

Lowland indigenous marchers who survived Chaparina say they have been doubly victimized by the repression and by the government’s denial of justice (or seeming indifference). On the occasion of the anniversary, human rights Ombudsman Rolando Villena accused the Morales government of “impunity and delay” in carrying out the investigation. Villena, whose October 2011 report held Llorenti and his subordinates responsible for the intervention, called for Llorenti to be suspended from his UN post and recalled to Bolivia to clarify his involvement.

Lowland indigenous marchers who survived Chaparina say they have been doubly victimized by the repression and by the government’s denial of justice (or seeming indifference). On the occasion of the anniversary, human rights Ombudsman Rolando Villena accused the Morales government of “impunity and delay” in carrying out the investigation. Villena, whose October 2011 report held Llorenti and his subordinates responsible for the intervention, called for Llorenti to be suspended from his UN post and recalled to Bolivia to clarify his involvement.

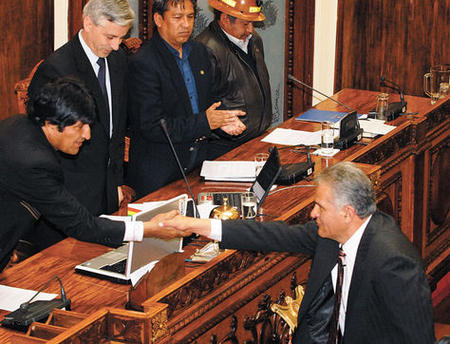

In response, Morales has repudiated Villena—whom he had previously promoted for the position—as an “instrument of the right.” Congressional deputies from Morales’s MAS (Movement Towards Socialism) party have demanded Villena’s resignation. (The Ombudsman is elected by two-thirds vote of Congress for a 5-year term; Villena was elected in 2010.)

In other TIPNIS news, Bolivia’s highest court has ordered a suspension of the judicial process against indigenous leaders Adolfo Chávez, Fernando Vargas, and Pedro Nuni. The three are charged with attempted homicide in relation to an incident of public whiplashing involving an indigenous leader who supports the TIPNIS road. The court agreed to consider whether the case falls under the jurisdiction of community justice, as the defendants claim. The three ended their self-imposed internal exile at the headquarters of the TIPNIS Subcentral (to avoid detention) after 88 days.

The Morales government has continued its efforts to eliminate extreme poverty in the TIPNIS, a target it has promised to achieve before taking further steps to build the road. In early November, Morales launched community development projects linked to cattle-raising, crafts, and tourism in 30 TIPNIS communities. Members of neighboring indigenous territories have complained that government resources are being diverted from their communities to the TIPNIS.

Finally, on November 10, Fernando Vergas was a special guest at an event held by the center-right opposition party MSM (Movement Without Fear) to launch the presidential campaign of Juan del Granado, a former MAS ally. The MSM is exploring alliances with conservative sectors to present a united front against Morales.

Emily Achtenberg is an urban planner and the author of NACLA’s weekly blog Rebel Currents, covering Latin American social movements and progressive governments (nacla.org/blog/rebel-currents).