This article first appeared in The Nation on October 22, 2013

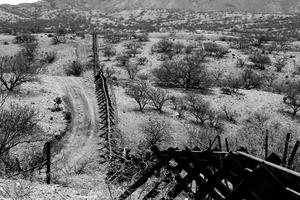

No one knows how many migrants have died trying to cross the desert into the United States. The US Border Patrol reports more than 5,500 deaths since 1998. Immigrant rights groups, like the Tucson-based Coalición de Derechos Humanos, estimate that the remains of at least 6,000 people have been recovered. These numbers certainly are just a fraction of the actual toll. The border is nearly 2,000 miles long, and as Kat Rodríguez, a spokeswoman for the Coalición, says, “The desert is a big place.”

No one knows how many migrants have died trying to cross the desert into the United States. The US Border Patrol reports more than 5,500 deaths since 1998. Immigrant rights groups, like the Tucson-based Coalición de Derechos Humanos, estimate that the remains of at least 6,000 people have been recovered. These numbers certainly are just a fraction of the actual toll. The border is nearly 2,000 miles long, and as Kat Rodríguez, a spokeswoman for the Coalición, says, “The desert is a big place.”

Exhausted migrants crawl into caves and die, their remains never recovered or their bones, picked clean by carrion birds and other animals, disappearing into the sand. A Texas rancher recently told a reporter that only one out of every four bodies is found, which would put the death toll at well over 20,000. Patrick Ball, a statistician who works with human rights groups to count the victims of mass atrocities—93,000 in Syria, 69,000 in Peru, 18,000 in Timor-Leste—says that in order to arrive at an accurate ratio of total dead migrants to known remains, one would need “several independent enumerations of people you can identify as having died in the way you’re studying.” Each list would have to survey roughly the same area of the desert and include the name of the victim and the approximate location and date of death.

But migrants often don’t travel with identification, and the reliable data that do exist are spread out over California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas, fragmented among morgues, hospitals, police departments and the Border Patrol. Some of those who perish during the trek don’t do so until they are well into the United States or have staggered back into Mexico. Robin Reineke, an anthropologist who works with the Missing Migrant Project, part of the nonprofit Colibrí Center for Human Rights, reports that the Tucson morgue alone has a catalog of more than 800 bodies awaiting identification. The project itself has a database of more than 1,500 missing people who were known to have crossed the border. Just a day in the desert sun, Reineke says, can render a corpse unrecognizable. First it distends; then the skin cures and blackens, often disappearing altogether, leaving T-shirts, jeans and sneakers hanging off bones. Going through pockets and backpacks trying to identify remains, Reineke has found handwritten letters, sewing kits, English-Spanish dictionaries, faded photographs, prayer cards, children’s drawings and slips of paper with an address and the words mi mamá.The Washington Post writes that the Brooks County sheriff’s office in South Texas keeps three white binders containing photos of the remains of dead migrants: “They are a gallery of horrors.”

Most die of dehydration, hyperthermia or hypothermia, but over the years migrants have testified to witnessing men wearing camouflage and driving civilian vehicles shooting and killing other migrants. Organized vigilantism started around 2000, when a group of ranchers in Cochise County, Arizona, began forming armed patrols of the border and issued a call for volunteers to join them. An anonymous flier was distributed among campgrounds in the Southwest inviting outsiders to bring their RVs, scopes, guns, signal flares and halogen spotlights to have some “fun in the sun” by joining a “Neighborhood Ranch Watch.” The border became a magnet for white supremacists, Nazis, nativists and militia members, many of them from the diverse right-wing “patriot” groups that had gained strength in the United States throughout the 1990s, since the end of the Cold War. Mexican consuls in border cities began receiving reports from migrants that they were being “hunted,” held at gunpoint, cursed and abused, and threatened with dogs. Others were shot, some killed. One unidentified male body was found in Cochise County with rope burns around the neck, as if lynched. Posses were capturing Mexicans and marching them by the score in coffles to be turned over to the Border Patrol. “Humans. That’s the greatest prey there is on earth,” said Roger Barnett, one of the Arizona ranchers often credited with starting the patrols.

The Mexican government filed complaints with the US State Department and the United Nations, demanding that the government rein in what it denounced as “paramilitarism.” The problem, though, was that US policy had created the crisis. In 1994, the North American Free Trade Agreement and Operation Gatekeeper, which began Washington’s militarization of the border, went into effect, with the two initiatives working as a pincer movement: in Mexico, NAFTA shut down factories, devastated rural communities and bankrupted small family farms, producing a stream of economic refugees flowing north; Gatekeeper and subsequent programs choked off established and relatively safe urban crossing routes, like those around El Paso and San Diego, forcing migrants to try their luck on more treacherous ground, across either the mesquite flatlands of South Texas or the gulches and plateaus of the Arizona desert, where private border patrollers make the crossing even more dangerous.

Harel Shapira’s Waiting for José is a sympathetic study of the Minuteman Civil Defense Corps, which at one point was the largest, best organized and most media-savvy of the border’s many volunteer watch groups. Shapira clocked more than 300 hours patrolling with the MCDC, basing his research on extended conversations with a handful of grunts between 2005 and 2008. The book is a useful reminder that the right-wing populism associated with the Tea Party predates the election of Barack Obama and can be traced back to the anti-Latino activism that began during the administration of George W. Bush.

But Shapira says we shouldn’t view the Minuteman movement as right-wing. To do so, he argues, does injustice to the complexity of its members’ belief systems and overlooks the link between their disquiet and a deeper malaise shared by many ordinary Americans. True, they are all armed to the teeth, and they all criticize Mexicans, describing them as the “cancer of our society” and believing them to be, interchangeably, drug runners, foot soldiers of a stealth reconquest of the Southwest or the cat’s paw of Islamic terrorism. But what brings members of the corps to the border, Shapira writes, “is less a set of beliefs about Mexicans than a sense of nostalgia for days long past when their lives had purpose and meaning and when they felt like they were participating in making this country.” Tired of bowling alone, they come together to hunt Mexicans. But what matters is the coming together; the hunting is incidental.

* * *

“We aren’t here to catch Mexicans,” Shapira says of his own experience patrolling the border with the Minutemen. Rather, he writes that the MCDC’s volunteers—nearly all of them war veterans—are looking for a “particular form of associational life; they are looking for male spaces, spaces where they can carry guns and be soldiers at war, spaces where the way they have learned to be in the world through previous life experiences makes sense,” where they can “attain a sense of self-worth.” The Minutemen’s striving for “belonging,” he believes, places them not at the margin but in the mainstream of American political culture. Their actions “resonate with a liberal democratic politics,” and the camaraderie they create at the border achieves what “our whole liberal democratic political tradition” wants citizens to be: “engaged, active, and concerned.”

It would be easy to quibble with Shapira for reducing liberalism to political action—vigilante justice, no less—and rooting citizenship in the rituals of masculinity and war. But there is something unwittingly contrarian about his book: for all its empathy with the paramilitarist xenophobia of the Minutemen, its findings can also be used to criticize American liberalism by excavating its settler-colonial foundation.

Frederick Jackson Turner is the most famous in a long line of observers who have argued that America’s exceptional political culture was formed in its borderlands. “The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward explain American development.” That was how he began his 1893 essay, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” Louis Hartz, in The Liberal Tradition in America, published in 1955, downplayed the importance of the frontier as such but did emphasize the supposed social emptiness of the American continent, especially the fact that liberalism had no serious ideological contender, neither aristocracy nor socialism, and therefore was never forced to evolve into a more mature, self-aware politics. Twenty years later, the political theorist Michael Paul Rogin combined Turner and Hartz and folded in the obvious: American liberalism might not have had feudalism to fight against, but it did have Native Americans and Mexicans. A century of race war across the continent, Rogin argued in Fathers and Children: Andrew Jackson and the Subjugation of the American Indian, allowed white men to psychically reproduce the ideal of a disciplined, property-holding and natural-rights-bearing self, even as capitalism was eroding the social foundation of that ideal, destroying traditional sources of power like the patriarchal family and creating, through wage labor and debt, new, insidiously abstract forms of bondage. Rogin died shortly after 9/11, but he would have recognized Shapira’s description of men who defined their freedom against Mexican slavishness and who tried to overcome their “isolation” and “alienation” through the fantasy of a never-ending war. He might even have called it liberalism.

Shapira is a sociologist, but there is little in the way of sociology in Waiting for José. Other sociologists, including Michael Kimmel and Abby Ferber, and journalists such as Joel Dyer, have argued that the rise of the militia right in the 1990s is directly traceable to federal policies put into place after the collapse of Keynesianism in the 1970s. Brutally high interest rates led to the offshoring of US manufacturing and made credit too expensive for the average farmer; agricultural legislation favored industrialized, low-priced food production, leading to the destruction of upward of a million family farms; and trade, labor and immigration policies ensured that there was no bottom limit on how low wages could fall. The destruction wrought by NAFTA on rural Mexico in the 1990s, then, was actually the second stage of a unified assault first launched on American farms and factories a decade earlier. A remark of Dwight Eisenhower’s from his first inaugural address—“whatever America hopes to bring to pass in the world must first come to pass in the heart of America”—has turned out to be double-edged.

Shapira, though, avoids making larger specific arguments regarding politics, economics and the rise of border vigilantism. He keeps his analysis gauzy and close to the heart: the men he writes about are saddened by a “loss of community,” made vulnerable by a “forfeiture of deep relationships.” Such small-bore analysis makes one yearn for some conceptual Lebensraum, to return to the Hegelian sweep of Turner and his interpreters and ask: What is the significance of the frontier to America today?

* * *

Turner said that the actual frontier had closed in the late nineteenth century, after a census reported that there was no part of the nation’s territory left unsettled. But he—and others who followed—thought that the frontier survived as a state of mind. In the mythology of Manifest Destiny, to move through the vast, pure space of the West was to skip the present and force the future. To face west was to face the Promised Land, an Edenic realm where the American as the new Adam could imagine himself free from nature’s limits and history’s ambiguities. The idea of the frontier, wrote the historian William Appleman Williams in 1974, was “exhilarating in a psychological and philosophical sense” because it could be “projected to infinity.” “There was no thought of drawing back,” wrote Woodrow Wilson, then a Princeton historian, in his version of the frontier thesis (Turner’s more prominent essay was published the same year).

Turner and others identified the frontier as the seedbed of what came to be known as American Exceptionalism. “The picture is a very singular one!” said Wilson—of roughened men “living to begin something new every day.” More recently, though, the frontier, as represented by the US-Mexican border, has become history’s sinkhole, the place where the past chokes on itself. For the vigilantes Shapira studies, the place is a site of enervating comparison with the past, one front of many in an exhausting global war. Vigilantes travel to the border to relive ancient memories of far-away battles, to recapture the fellowship they once enjoyed in Southeast Asia, Iraq or Afghanistan. As they rehearse how Vietnam could have been won, they raise the Gadsden flag and imagine themselves as the rear guard of the Mexican-American War of 1846–48, holding the line against an enemy they believe is intent on retaking land they lost at the end of that conflict, which includes California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, Colorado and Arizona. “You know, people across that border are probably still sitting around campfires talking about how they lost the war to us,” one volunteer tells Shapira, acknowledging that whites “took this land by conquest.” History’s ambiguities are very much alive, flickering around the political unconscious of the border vigilantes like the shadows cast by campfires in the desert night. The word most often used to describe Mexico’s supposed bid at restoration, reconquista, was originally used by Spaniards to describe their crusade, starting in 722 and ending in 1492 (a long war if ever there was one), to retake the Iberian peninsula from Arab and Berber Muslim colonists—which equates, if the analogy is extended, the Minutemen to Muslim usurpers.

Shapira, who tells readers he was born in Israel, was kicked out the first time he arrived at the Minutemen’s camp in southern Arizona, accused of being a member of the ACLU. But after cutting his hair and putting on his father’s IDF-issued pants, Shapira returned. This time he was in. “He’s from Israel,” was how one Minuteman would introduce him to another. Volunteers repeatedly brought up Israeli politics, including clashes in the occupied territories, and sought out Shapira’s opinion on the “Israeli fence” the MCDC was taking upon itself to build. Cowboys of old carried Colts, Winchesters and Springfields, but the Minutemen proudly passed their Austrian Glocks—the same kind of sidearm the IDF apparently uses—to Shapira for inspection. “You know there is no group of people I have more respect for than the Israelis,” said a patroller named Earl upon meeting Shapira. “This is our Gaza.”

Historians have largely discounted the argument that the American West worked as a “safety valve” for class tensions in the East. But throughout the twentieth century, presidents found that appealing to what Wilson called America’s “frontier heart” was an effective way of simplifying the complexities of the modern world, of sublimating domestic political conflict into the myth of limitless expansion. Richard Nixon generally avoided pioneer symbolism, which might have had less to do with wanting to distance himself from JFK’s New Frontier—or with the Vietnamese, whose tenacity revealed that there were indeed constraints on American power—than with the fact that when he was a boy, he worked as a barker at Dick’s Wheel of Fortune at the annual Frontier Days summer rodeo in Prescott, Arizona. As a politician, he could put that experience behind him and try a different hustle.

No one milked the myth better than Ronald Reagan, who invoked a morality “born and bred in the wide open spaces” to restore certainty to American politics after defeat in Vietnam. “The difference between right and wrong,” he said in 1983, “seems as clear as the white hats that the cowboys in Hollywood pictures always wore so you’d know right from the beginning who was the good guy.”

Reagan’s escalation of the arms race with the Soviet Union and push into the Third World was objectively important in helping the United States restore its supremacy after losing its grip on Iran, Nicaragua and Southeast Asia. But his revival of the Cold War also kept busy the contentious theocon and neocon factions of the New Right, which otherwise might have focused their fire on his many domestic compromises with the Democratic establishment (on, among other things, immigration legislation). He empowered an interagency group of men, headed by Oliver North, who collectively called themselves the “cowboys,” to run foreign policy as if it were a revival of Bill Hickok’s Wild West Show. Iran-Contra, as the various scandals involving the cowboys became known, was as much a crime as a romance, a bid—and a successful one for a time—to reopen the frontier through counterinsurgency in Central America and elsewhere.

* * *

At this point, the frontier is a dead metaphor. It was done in partly by Reagan himself. People tend to remember him as the embodiment of rawhide authenticity, but he performed his role as rancher-president with a twinkle of Brechtian irony. Reagan even once quoted the liberal historian Henry Steele Commager, admitting that the public knew there was a difference between “myth” and “reality,” but it didn’t matter: “Americans believed about the West not so much what was true, but what they thought ought to be true.” Such historical self-awareness made it hard for his successors, like George W. Bush, and would-be successors, like Texas Governor Rick Perry, to play it straight.

But it was the disasters in Iraq and Afghanistan, along with the 2008 economic collapse, that ultimately killed the frontier as an ideal. Washington is still waging a worldwide counterinsurgency, with military bases that span the globe. And Barack Obama did have one cowboy moment, when he sent SEAL Team Six to kill “Geronimo,” as Osama bin Laden was code-named. Obama’s submission to the premises of the national security state has been total, yet for the most part he’s secularized the imperium, reframing militarism as a matter of utility, competence and pragmatism—technocracy. This has made it difficult for the right to muster itself through war and foreign policy. With backroom supervisors preparing kill lists and game boys flying the drones, the romance is over.

In the last decade, “quick-draw” corporate mercenaries were let loose to re-create the death cult of the West in what they called “Indian country,” the Iraqi and Afghani provinces of Kandahar, Najaf and Anbar, turning the cities of Fallujah, Ramadi and others into Tombstones. Outfits like Blackwater were as much Christianist as militarist, which allowed them to play the same role that Iran-Contra did in the 1980s by uniting in a foreign campaign the Kit Carson Indian-killing and Elmer Gantry evangelical wings of the conservative movement. But many of these companies have gone international, which undercuts their ability to aggregate the nationalist right.

Erik Prince, for instance, the founder of Blackwater, still has gun and will travel. But he’s decamped to Abu Dhabi, where he is being bankrolled by emirate oil money to start up a new battalion of mercenaries, staffed mostly by Colombians and South Africans. Prince has two missions: to ensure that the kind of mass demonstrations that occurred in Egypt, Tunisia, Bahrain and elsewhere don’t take place in the United Arab Emirates, and to suppress piracy in sub-Saharan Africa, making the continent safe for corporations looking to tap into its mineral wealth, including Prince’s own Frontier Resources Group, which he started with private and state Chinese capital. The frontier is now multilateral, and the kinds of men who find themselves on the US-Mexican border no longer have access to it. They are tin soldiers.

With nowhere left to go, the “furies” of the right, as Sam Tanenhaus describes the conservative fringe, whip around the homeland, revealing the supremacist roots of America’s settler tradition. Ideas that in the past had been suppressed, or deflected into war, now burst out in domestic policy. Conservative activists and politicians can’t mention healthcare without turning the discussion to rape. Bring up taxes, and suddenly they are stuttering on about slavery. On the border, Mexican-hating has become metaphysical: they are waiting for José but thinking about Abdul. Many of the vigilantes that Shapira talks to say they would rather be killing Muslims over there. But they can’t. So they ambush Mexicans and Central Americans here. The rise of the Minuteman movement corresponded with a spike in anti-Latino hate crimes, which according to the FBI increased 40 percent between 2003 and 2007. It’s an old tradition. According to William Carrigan and Clive Webb in their recently published book, Forgotten Dead: Mob Violence Against Mexicans in the United States, white vigilantes in the Southwest lynched an unknown number of Mexicans between 1848 and 1928, with conservative estimates putting the tally in the thousands.

* * *

Shapira says he wants to understand the Minutemen, but in fact he pities them. His portrayal of one pseudonymously named volunteer is indistinguishable from another, with “Earl,” “Gordon” and “Floyd” dissolving into a lost platoon of man-boys searching for meaning in the desert. They all say straight up that they don’t like Mexicans, but Shapira knows that what they really want is acceptance and appreciation. They do seem sad, these aging white veterans of foreign wars sitting in lawn chairs, scanning the desert with their thermal binoculars. Their nostalgia is free-floating and their bigotry seems farcical, considering it’s directed mostly at people who represent ideals that the Minutemen say they value. Strip-mall America would be even more barren if it weren’t for the pockets of Mexicans and Central Americans who have taken over empty stores and turned them into taquerías, carnicerías, pupuserías, peluquerías and other enterprises.

Except that the Minutemen have largely won the national debate. Since the founding of the MCDC in 2005, Washington has doubled the number of Border Patrol agents and quadrupled the amount of fencing separating the United States from Mexico. As president, Bush condemned the Minutemen as “vigilantes,” yet he put into place Operation Streamline, which prosecutes, tries and deports migrants en masse, a program that continues despite being strongly criticized by civil rights lawyers. The Democrats are the party of immigration reform, but they have conceded the debate to those who insist that “effective security” at the border is the precondition to legalizing the status of the estimated 11 million undocumented residents in the United States. The Senate’s bill, which passed in June, is “tough as nails,” says its chief sponsor, New York Senator Charles Schumer, providing billions more for policing, fencing and deporting but not a penny for the water stations or greater cellphone coverage that might save lives.

Turner depicted the borderlands as a place where individualism sprouted from the land like prairie weeds, and only after did government and big business arrive. But as Reagan might have said, that is the myth. The reality is that what we think of the West since its inception has been the domain of large corporations, including railroads, real estate, agriculture and mining. “Settlement tended to follow, rather than precede, connections to national and international markets,” the Stanford University historian Richard White argues—markets that were themselves created by federal action and protected by federal troops. In this sense, proposed immigration reform legislation, with its punitive, costly path to citizenship and further militarization, will make the border more of what it has always been: a vast private-public partnership.

In the last two decades, federal trade, farm and immigration policy has been combined to create a three-tiered, nested market: free and common for capital; protected for US agriculture; divided and garrisoned for labor. Mexico can stay competitive with the United States only by keeping its hourly pay brutally low—a fifth lower than China’s. Wages are worse in Central America, which now has its own free trade treaty with Washington. South of the border, the price of US-imported and subsidized corn hovers in what might be called the Cargill sweet spot: high enough to generate widespread hunger, but not so high that local farmers can compete. In Mexico and Central America, an ever-greater percentage of the corn that is planted, along with sugar and African palm, is directed to produce biofuels, the demand for which is kept artificially high by yet more Washington subsidies, which further raises the cost of local food, accelerates rural dislocation and spurs migration. Meanwhile, the more militarized the border, the more fearful those workers who do make it across are of being deported and forced to cross again—a vulnerability that puts sustained downward pressure on wages in the United States, not just among undocumented workers but throughout the whole low-skill labor sector.

* * *

The Minuteman Civil Defense Corps no longer exists, having splintered into a number of smaller vigilante and militia groups. Shapira hints that one of its problems was that the emasculation that many of its rank-and-file volunteers felt in society at large was replicated within the corps itself. Under close watch by groups like the ACLU, infiltrated by undercover reporters, and looking to avoid the kind of criticism that was directed at earlier rancher-vigilantes, the MCDC established strict rules as to what patrollers could do if they encountered migrants. They couldn’t pursue or apprehend them. They couldn’t even, on orders from the Border Patrol, “light them up”—that is, track their targets with bright floodlights.

On the off chance that the volunteers were to spot a “José” or “María,” all they could do was call in the sighting and wait for the feds to show up. Shapira reports general grousing about these restraints. Others, including the Southern Poverty Law Center, say the group gave up its corporate status because it didn’t want to be legally responsible for the “actions of its fired-up volunteers,” many of whom apparently were tired of the rules and wanted to get back to the days of hunting, capturing and tying up migrants by the dozens. Just a year before the breakup, members of a rogue Minuteman unit broke into the home of a Latino family in southern Arizona, killing a man and his 9-year-old daughter, Brisenia Flores, and badly wounding his wife. (More recently, one of the original founders of the Minutemen, Chris Simcox, featured prominently in Shapira’s book, was arrested for sexually assaulting three girls under the age of 10.)

Last year, the number of people crossing into the United States from Mexico without a visa dropped significantly, largely due to the United States’ poor economy. The number of known total desert deaths, however, rose—from 375 in 2011 to 447 in 2012, up 27 percent. Yet border militarization remains a racket, directing billions of federal dollars to the defense industry and private contractors, like the Corrections Corporation of America and the Geo Group, which are in charge of incarcerating and expelling migrants. If it should become law, the Senate’s immigration bill will spend $46 billion on border security, on top of the $18 billion already budgeted annually for immigration enforcement. According to The New York Times, with the wind-down in Iraq and Afghanistan, defense contractors like Lockheed Martin are betting on a “military-style buildup at the border zone,” hoping to supply helicopters, heat-seeking cameras, radiation detectors, virtual fences, watchtowers, ships and military-grade radar. Senator Patrick Leahy has called one Republican proposal “a Christmas wish list for Halliburton.” Ten Predator drones already patrol the skies, and defense lobbyists are pushing for more. The Times also describes a prototype ground sensor linked to a command center in Tucson that apparently resembles the set of Steven Spielberg’s science fiction film Minority Report. Maybe the border still is the future: the highest tech used to secure the lowest wages.

Greg Grandin teaches history at New York University and is the author of Fordlandia, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize...