On February 17, Rene Meza Huerta drove on a short errand through the streets of South Tucson, Arizona, with his girlfriend and their children. Huerta is a Mexican national who was in the process of getting his U.S. citizenship. Police pulled him over because of a seatbelt infraction. “Please, don’t arrest me, I have six children to care for!” he told them. Police arrested Huerta anyway, despite his pleas and the young children watching at close range. After a routine Secure Communities database check, the police called Border Patrol. Their vehicles arrived at the scene, and within minutes the Border Patrol placed Huerta under arrest.

This arrest of a parent of young U.S. citizen children, repeated countless times daily across the country, caught the ire of a young day labor organizer riding by on his bicycle. After exhorting law enforcement not to arrest the dad, Raul Alcaraz Ochoa, 29 and single, decided he had had enough of the daily diet of Homeland Security’s detention and deportation breaking up families. He crawled under the vehicle about to take Huerta away. Eventually Border Patrol forced him out with pepper spray, handcuffed and arrested him, and took him away. That evening, hundreds of supporters called Border Patrol demanding his release, and he was out within 24 hours. Rene Meza Huerta was not so lucky. Detained in isolation in Tucson, despite scores of calls to Washington to release him to alternative detention, within days Border Patrol put him in a vehicle and dumped him over the border into Nogales, Sonora.

The children remained with Huerta's girlfriend, who vowed to care for all six, three of her own and three of his. A trio of underemployed but determined women—grandmother, aunt, and girlfriend—now care for the six children, all U.S. citizens, of stair-step ages, the youngest two-years-old, the oldest a pre-teen.

Ochoa talks about what frustrates him when U.S. immigration policies tear families apart and what drove him to lie down in front of the Border Patrol vehicle, despite all the risks inherent in this act of civil disobedience. He explains, "My family and I have been impacted by discrimination based on immigration status and race all my life. My parents came here to the United States when I was very young, and we lived in the shadows for years. I’ve had relatives detained and deported. Currently, my community deals with unemployment, lack of medical insurance, housing issues, and police harassment and detention on a regular basis. So to me injustice takes place on a daily basis. You know, there comes a point when you say 'ya basta!'—enough is enough.”

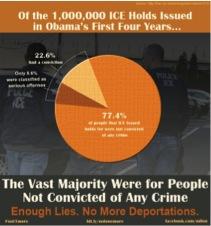

Between 2010 and 2012, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) issued deportation orders to 204,810 parents of U.S. citizen children over a 26-month period. Filmmaker Roberto Lugones of France’s ARTE-TV brought a crew to Arizona last summer to film the phenomenon of families divided due to ICE detention and deportation. He emphasized, “In France, we do some not so great things with the immigrants, but we do not do this. We do not break up the families.”

On occasion, with the support of many people like Ochoa who organize in the border areas to challenge injustice, there are victories. Take the case of Paloma, a young mother separated from her two children for over a year by state protective services. Old unpaid traffic tickets came back to haunt her and, after her arrest and against her express wishes, immigration authorities quickly deported her. From Nogales, Sonora, Paloma did whatever she could to comply with a case plan—attending every scheduled court hearing by telephone, regularly contact her lawyers, meeting home inspection standards, and staying in touch with her kids by letter and phone to win her little daughter back. Early in February, her battle paid off. Officials crossed over with the child, stuffed elephant and bicycle in tow, and mother and daughter were tearfully reunited at a Mexico government office. Amidst tears of happiness, Paloma declared, ”Somos las madres de la revolución, batallando por nuestros hijos”—we are the mothers of the revolution, fighting for our kids.

But what happens to most of the children left behind when caregiver parents are deported? Mariana, a mother of four whose husband was deported following a minor traffic accident, explained sadly, “My children are always afraid. They say ‘Mami, mami, be careful, police behind us!” They don’t want me to go out driving alone. They have nightmares. Sometimes when there’s bad news about an immigrant, they don’t even want to go to school. They are frightened someone will come and take me away. We, the parents, never know when we leave home, if we will come back. “

As a day laborer organizer, Raul Alcaraz Ochoa knows hundreds of these families. He sees off the single men and dads recruited for a day’s work. He hears about when they get busted and detained. If they do, he and the “red de protección“—the day laborer protection network—provide support to those left behind. He describes their work, saying ”We provide worker center members with legal help, and letters when people are in detention. We visit them in detention, too, go to court hearings, and support family members with resources, fundraise to pay their hefty bonds, and arrange food and shelter on the other side for the ones who get deported.” Raul agrees with Mariana, “They leave home for work in the morning, and sometimes they never come back.”

This reality motivated Raul to put himself on the line—because enough is enough.

Laurie Melrood lives in Tucson and is a long-time immigrants rights advocate. See also "Children As Collateral Damage," by Joseph Nevins, November 7, 2011. For more from the Border Wars blog, visit nacla.org/blog/border-wars. And now you can follow it on twitter @NACLABorderWars. See also the May/June 2011 NACLA Report, Mexico's Drug Crisis; the Jan/Feb 2009 NACLA Report, Taking on Policy in the Obama Era; and the May/June 2007 NACLA Report, Of Migrants & Minutemen.