What does—and should—constitute security can be a complicated and controversial matter. But you wouldn’t know this if you only talked to the U.S. Border Patrol and White House staffers, or read The New York Times on March 16.

In one article, a top-of-the-fold, front-page piece entitled “Arizona Border Quiets After Gains in Security,” reporter Julia Preston effectively regurgitates the Department of Homeland Security’s press statements. She tells us what its spokespeople say—and little else—about the U.S.-Mexico borderlands.

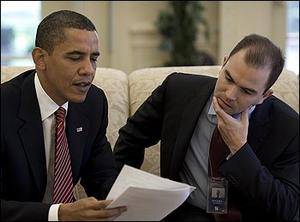

In a different “security”-focused article, positioned right next to Preston’s, readers are introduced to Benjamin J. Rhodes. He is, writes Mark Landler, “a 35-year-old- deputy national security adviser with a soft voice, strong opinions, and a reputation around the White House as the man who channels Mr. Obama on foreign policy.” As suggested by the gushing description and a title of “Worldly at 35, And Shaping Obama’s Voice,” the article, like Preston’s, is one that reads almost as if someone from the Obama administration had penned it.

Together, the two articles exhibit the tendency of all-too-many mainstream journalists to defer to U.S. authority and uncritically repeat the worldview of the country’s ruling class. They also demonstrate how unjustly advantaged groups produce security—in terms of its supposed need. It is in part by downplaying at best the harm done to those on the receiving end of “security,” and by ignoring the larger structures of injustice that in some ways require brutality for their maintenance.

In Preston’s article, readers meet Sabri Dikman, the Border Patrol’s “executive officer” for the Tucson region as he watches live images in an “intelligence center” taken by a drone aircraft and surveillance towers in the border region. Dikman, Preston reports, “liked what he saw—and what he did not see” (unauthorized migrants trying to enter the United States). This reflects a policing apparatus now so effective, one learns, that “[b]order officia ls, once a beleaguered force overwhelmed by illegal flows, have acquired a bit of swagger.”

ls, once a beleaguered force overwhelmed by illegal flows, have acquired a bit of swagger.”

With seemingly markedly lower numbers of individuals trying to cross the boundary surreptitiously, Preston states, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), is now in a position to focus on “more troublesome adversaries”—namely professional smugglers. But these aren’t individual entrepreneurs, according to Jeffrey Self, the head of the CBP’s Joint Field Command for Arizona. “It’s pretty much all organized smuggling at this point and its pretty much all controlled by the transnational criminal organizations” in Mexico, "particularly those linked to narcotics.”

Preston quotes Self without comment. She thus ignores the fact that, as David Spener, author of Clandestine Crossings, points out, claims by U.S. authorities of a takeover of migrant smuggling by drug traffickers—ones the sociologist has found to be “quite exaggerated”—go back to at least the 1970s. But such findings are seemingly non-existent in Preston’s world—to say nothing of how the very boundary policing build-up can give rise to a need for ever-more-sophisticated smuggling efforts.

While Preston constructs security as necessary in the face of nefarious threats from south of the border, Landler’s puff piece on Rhodes seems to suggest that security is required to make the world a better place for all. As exemplified by Rhodes’ push for U.S. backing of “a NATO military intervention in Libya to head off a slaughter by Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi” (reports of which, it turns out, were greatly exaggerated) to his championing of “more aggressive efforts to support the Syrian opposition,” Rhodes, readers hear from Denis McDonough, the White House chief of staff, “cares about people.”

An aspiring novelist, Rhodes is the author of the speech—one that “is likely to focus on America’s unshakeable support for Israel,” according to Landler—that Obama will deliver during his current visit to Israel. (The visit includes a quick side-trip, via helicopter, to the occupied West Bank, which will allow him to ignore Israeli boundary controls and checkpoints.) It is a speech that will very likely say little to nothing of substance about the suffering of Palestinians, the underlying Israeli policies, and U.S. complicity in Israel’s crimes. This despite the deep care that Rhodes has for people.

An aspiring novelist, Rhodes is the author of the speech—one that “is likely to focus on America’s unshakeable support for Israel,” according to Landler—that Obama will deliver during his current visit to Israel. (The visit includes a quick side-trip, via helicopter, to the occupied West Bank, which will allow him to ignore Israeli boundary controls and checkpoints.) It is a speech that will very likely say little to nothing of substance about the suffering of Palestinians, the underlying Israeli policies, and U.S. complicity in Israel’s crimes. This despite the deep care that Rhodes has for people.

Such silence—like the very short-shrift Preston affords to what she calls the "human toll" of "border security"—speaks to the particular variant of worldliness embodied by Rhodes and the administration he serves, and the narrowness of security championed by the White House. It is one in which care and protection are extended only to a privileged few. For those not allied with U.S. interests and its allies, for those who refuse to accept the established order embraced by Washington, they are on the receiving end of the proverbial stick of empire, ones justified in the name of security.

In situations of occupation whereby territory is gained through war, rights denied as a result, and the new status quo maintained through various forms of violence, ending the injustice requires new conceptualizations of security, and the struggles to realize them. This applies to the U.S.-Mexico borderlands, Palestine-Israel, and many other places where a security of a truly human sort is lacking for the geopolitically and socio-economically dispossessed.

Joseph Nevins teaches geography at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York. Among his books are Dying to Live: A Story of U.S. Immigration in an Age of Global Apartheid (City Lights/Open Media, 2008) and Operation Gatekeeper and Beyond: The War on “Illegals” and the Remaking of the U.S.-Mexico Boundary (Routledge, 2010). For more from the Border Wars blog, visit nacla.org/blog/border-wars. Now you can follow it on Twitter @NACLABorderWars.