Bolivian President Evo Morales has promised to eliminate extreme poverty in the Isiboro-Sécure Indigenous Territory and National Park (TIPNIS), before taking any further steps to design, fund, and build the controversial highway that would bisect the reserve. The decision is expected to put the highway on hold for three years, until the end of 2015.

The surprise announcement comes as lowlands indigenous groups and their supporters continue to challenge the highway on a variety of fronts, and as Bolivia gears up for the 2014 presidential elections. Morales is again the declared candidate of the Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) party, notwithstanding the current controversy over whether a third presidential term is constitutionally permissible.

The Morales government has committed $14 million over the next two years for basic services (water, electricity, health, and education), transportation, telecommunications, natural disaster prevention, and sustainable development projects in the TIPNIS. According to Juan Ramón Quintana, who is overseeing the anti-poverty effort, more than $2 million has already been invested (presumably reflecting the government’s widespread practice of delivering outboard motors, chainsaws, solar panels, electric generators, and similar benefits to communities during the official consultation process on the TIPNIS road, which has been highly controversial).

The Morales government has committed $14 million over the next two years for basic services (water, electricity, health, and education), transportation, telecommunications, natural disaster prevention, and sustainable development projects in the TIPNIS. According to Juan Ramón Quintana, who is overseeing the anti-poverty effort, more than $2 million has already been invested (presumably reflecting the government’s widespread practice of delivering outboard motors, chainsaws, solar panels, electric generators, and similar benefits to communities during the official consultation process on the TIPNIS road, which has been highly controversial).

By October, says Quintana, the TIPNIS will be the first indigenous territory to achieve 100% documentation, through the distribution of birth certificates and identity cards to every inhabitant. An “ecological regiment” has been launched to carry out park security, ecotourism, sustainable development, and training activities for indigenous youth.

While MAS deputies initially announced that the legislature would not seek to initiate or modify any existing laws affecting the TIPNIS during the three-year period, Quintana has suggested that the law protecting the reserve’s “untouchable” status will need to be altered or substituted, in accordance with the ”mandate” of the consulta. According to official reports, all but one of the TIPNIS communities participating in the consulta voted to overturn the “untouchability” law—which the Morales government interprets as precluding sustainable development activities by native groups as well as major development projects like the highway.

The decision to prioritize anti-poverty efforts, government officials say, is a direct response to community demands articulated during the consulta process. Still, TIPNIS leaders remain skeptical. According to Adolfo Chávez, ending extreme poverty in the TIPNIS will require a deliberate strategy to enhance each community’s particular sustainable development initiatives, with the government guaranteeing prices and markets, and will cost at least three times as much as the amount promised. For Fernando Vargas, the program is little more than a strategy to guarantee eventual construction of the TIPNIS highway.

Alejandro Almaraz, former Minister of Lands in the Morales government who strongly opposes the TIPNIS road, sees the announcement as an admission of defeat by Morales. Despite exhaustive and multi-pronged efforts, he argues, the government has been unable to achieve the necessary social and legal conditions to construct the road. Morales will not be able to deliver the TIPNIS highway “like it or not, in the current adminstration,” as he famously promised in 2011.

The continuing polarization around the TIPNIS highway was evident last month in Washington DC, when TIPNIS leaders denounced the proposed highway and the consulta process before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). A counter-delegation of government officials and pro-government indigenous leaders presented the government’s point of view. Morales (along with Ecuador, Venezuela, and Nicaragua) has threatened to withdraw from the IACHR on the grounds that it reflects the ideology and priorities of its primary donors, the United States and Europe, and has been unduly critical of left-leaning Latin American governments.

The Catholic Church, which recently issued a report critical of the consulta process, has come under attack by pro-MAS groups and government officials. The pro-road CONISUR (an indigenous governing authority in the southern section of the park) has threatened to take over church lands within the TIPNIS and bar church representatives from entering the reserve. TIPNIS leaders also charge that increased militarization of the park has restricted their freedom of movement, forcing delays in a recent territory-wide congress when indigenous authorities could not get fuel, or permission from the Navy, for river travel.

Recent revelations in the Chaparina case—the official judicial investigation into the police repression of TIPNIS marchers in September 2011, which has dragged on for more than a year, with little progress—have also reignited tensions. Vice-President Alvaro García Linera has testified that neither he, Morales, nor then-Interior Minister Sacha Llorenti, had prior knowledge of the police intervention or know who gave the order to intervene—contradicting his earlier press statement that the government knows what happened.

Ex-Defense Minister Cecilia Chacón, who resigned in protest after Chaparina, has testified that Morales and other high-level cabinet officials were monitoring events by telephone immediately following the incident as the marchers were being evacuated—raising questions as to why the police were not ordered to retreat. The official government narrative, which holds that the police broke the “chain of command,” has been challenged by Bolivia’s human rights ombudsman, whose report points a finger at Llorenti. Llorenti has been officially excluded from the investigation and currently serves as Bolivia’s representative to the UN.

On the political and electoral fronts, the fallout from the TIPNIS crisis to date has been inconclusive. In the special Beni gubernatorial election last January, the conservative coalition candidate prevailed with 52% of the vote, but the MAS candidate gained 44% —a significant increase compared to the party’s 7% support registered in 2005. In the two provinces where the TIPNIS is located, MAS won 56% and 69% of the vote, respectively—further evidencing indigenous support for the road (for Morales), or the effectiveness of the government’s gifting campaign (for Adolfo Chávez).

On the political and electoral fronts, the fallout from the TIPNIS crisis to date has been inconclusive. In the special Beni gubernatorial election last January, the conservative coalition candidate prevailed with 52% of the vote, but the MAS candidate gained 44% —a significant increase compared to the party’s 7% support registered in 2005. In the two provinces where the TIPNIS is located, MAS won 56% and 69% of the vote, respectively—further evidencing indigenous support for the road (for Morales), or the effectiveness of the government’s gifting campaign (for Adolfo Chávez).

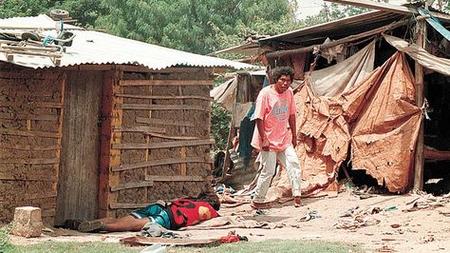

Indigenous leader and ex-MAS deputy Pedro Nuni, who ran independently for governor, gained only 2.65% of the vote. Nuni is now the Secretary of Indigenous Development in the conservative Beni administration. Miriam Yuvanore, a survivor of the TIPNIS police attack (whose iconic photo, showing her bound and gagged, has become a symbol of the event) is heading the TIPNIS subgovernment unit created by the new Beni governor.

As for the 2014 elections, both the original lowlands indigenous federation CIDOB (now challenged by a rival pro-government organization) and the highland indigenous federation CONAMAQ have announced that they will remain independent of any established political party. This represents the final rupture of the Unity Pact, the broad alliance of peasant and indigenous movements that have supported the MAS and Morales since 2005. The COB (Bolivian Workers Central) is in the process of creating its own political party.

Still, recent opinion polls show Morales maintaining a 59% support level in the major cities, apart from rural areas which are his major political base, with no viable challenger in sight. Putting the TIPNIS road on hold and defusing the conflict for a few years may be an insurance policy to guarantee his reelection. But whether the elimination of extreme poverty—if truly achieved—will represent a genuine or a Pyrrhic victory for inhabitants of the TIPNIS, only to be undermined later by construction of the highway, remains to be seen.

Emily Achtenberg is an urban planner and the author of NACLA’s weekly blog Rebel Currents, covering Latin American social movements and progressive governments (nacla.org/blog/rebel-currents).