Much of the text in this photo essay is excerpted from an article I originally published in the Tucson Weekly.

Everyone in our group of 52 people wakes up at 3 a.m. It's Thursday, May 30, and we are at a campsite on the northern edge of the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge, approximately 25 miles from the international border and 40 miles southwest of Tucson. The group is used to getting up early, but on this day, with 16 miles to cover, we need to beat our normal 5 a.m. start.

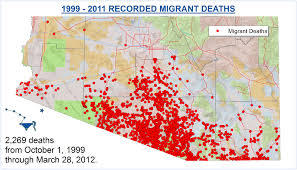

We have already been walking for three days, but this is the toughest day of the Migrant Trail Walk—a 75-mile, seven-day hike from the U.S.-Mexico border at Sasabe to Tucson. This is the 10th annual walk, which brings participants from Southern Arizona and around the world to walk in solidarity with the more than 6,000 migrants whose remains have been recovered in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands since the mid-1990s. The desert south of Tucson has been one of the deadliest places for unauthorized border-crossers.

The point of getting up at 3 a.m. is to get an early start, because once the sun rises in Southern Arizona in late May, it doesn't take long for everything to start to bake. The first three days of the walk have been uncharacteristically cool for this time of the year, with temperatures hovering in the lower 90s. That changes today, as a heat wave approaches that will launch the temperature to well above 100 degrees, creating the deadly conditions that have resulted in the dea so many people.

After we take down our tents and pack the four support vehicles that accompany us, we begin to walk, many with blistered and bandaged feet. It is still dark and the group walks in two files, most carrying a cross with the name of a person who died on the journey north into Arizona. On this first stretch, the walkers proceed in silence and, for some, in mourning. The ground is soft sand at this point, which makes it hard to walk, with ruts and crevices that aren't as visible in the dark. However, by the time we stop for our first water break, after two miles, the first soft light of morning comes over the mountains. With Baboquivari Peak to the west, there is a sense of beauty and peace in this place.

However, as the group turns onto Highway 286, which connects Sasabe to Three Points, it quickly becomes apparent that this area is not at all at peace. For the next two days we will walk along this two-lane road, and about half the vehicles we will see are green-striped Border Patrol trucks, sometimes carrying ATVs on long trailers, sometimes with mounted surveillance cameras, and often with cages on the backs used to detain captured migrants. Up the road at the Border Patrol checkpoint, the armed agents ask the walkers about their citizenship, as they do to the passengers in every vehicle that comes from the south. The feeling is not of peace, but of war.

Indeed, the very area that the Migrant Trail Walk traverses is one of the focal points of a vigorous national debate on comprehensive immigration reform, in which border policing has become a high priority. The way the bill now stands in the U.S. Senate, another $6.5 billion would bolster border enforcement apparatus that already has received unprecedented funds since the mid-1990s. And much of that would be spent on this area of Arizona.

Comprehensive immigration reform would bring an additional 3,500 Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents, the parent agency of the U.S. Border Patrol. This photo is from a Border Patrol rapid reaction unit.

Three billion dollars would go to border policing technology such as this mobile surveillance tower near where we walk. Constant drone surveillance is another mandate in the bill's current version.

The proposed immigration law calls for more fencing like the one in this photo between Sasabe, Arizona and Sasabe, Mexico. The border buildup is a continuation of Border Patrol policies enacted in 1994. This strategy militarized traditional urban crossing points to drive migration through more dangerous crossing areas like the Arizona desert. The “prevention through deterrence” strategy resulted in thousand of people entering the United States in desolate and dangerous parts of the desert in order to evade the walls and surveillance. The coffins above represent the thousands who have died trying.

Kat Rodriguez of Coalicion de Derechos Humanos says about the Migrant Trail Walk that "few of us who have been doing this the entire time thought that we would still be doing this 10 years later." This year, 77 bodies have been recovered in Arizona through April. On May 28, while the group walked, five more skeletal remains of presumed border-crossers were found close by on the Tohono O'odham Nation. Although the number of people crossing the border has declined in the last few years, migrant deaths remain high in Arizona. In fact, the proportion of people dying while trying to cross has grown. Rodriguez said that, "it is more likely that you will die now, than five years ago." In the last 10 years, the remains of more than 2,000 migrants have been recovered in Arizona. Many believe that there are many more remains still to be discovered.

"We don't say it's a failed policy," Rodriguez says, referring to the deaths, "we say it's a policy by design."

Cristen Vernon, a student from Michigan who is walking the migrant trail for the third time, tells me that "it's disgusting that the migrant deaths are not being discussed in this national debate." It's true. So far, the immigration reform debate continues as if these deaths have never happened.The cluster of red dots marks the spots where remains have been recovered and recorded. This is where we walk.

Sasabe, Sonora, native Natividad Cano and Migrant Trail walker remembers a time when there wasn't a wall, when the port of entry in Sasabe, Ariz., was a one-room adobe building. In the 1960s, when she was in fourth grade, she had to go to school across the border in Sasabe, Ariz. "The officer sitting inside his office would wave us through, especially during the heat or cold. He knew us." I ask Cano if she feels at home in the land where she is from anymore. She says no, "it doesn't belong to the people anymore, it belongs to the government." She says that it feels like an "occupied country."

Walker Olivia Mena of Austin, Texas, says, "I suppose that someone on the outside might wonder why are these people walking through the desert, what does that really help? But for me, as someone who formerly worked as a border reporter covering migrant deaths—I even accompanied migrants' bodies back to their homes in Mexico—it is important. And when you share in those kinds of experiences, you realize that those are the kind of people who get lost, they don't get an obituary in the paper here, nor do they show up in the public record or consciousness . . . "

Itzel Cozamayotl, at seven years old the youngest person to ever walk, tells me that she is excited "because I wanted to walk the migrant trail for several years, because I just wanted to finish the journey of the person on my cross or any person who died trying because they didn't have enough food or water."

A sweeping view of the Altar Valley at sunset. This is where we walked. What is difficult to reconcile is that it is also a "graveyard," according to Native American elder Maria Padilla. We walked not only close to the many who risked their lives in the June heat, we also walked among the dead.

Todd Miller has researched and written about U.S.-Mexican border issues for more than 10 years. He has worked on both sides of the border for BorderLinks in Tucson, Arizona, and Witness for Peace in Oaxaca, Mexico. He now writes on border and immigration issues for NACLA Report on the Americas and its blog “Border Wars,” among other places.