This post is part of our series on America: Migrant Journeys in collaboration with Global Voices. Stay tuned for more articles and podcasts.

Many migrants in Mexico once dreamt of reaching the United States. But cartel violence running along the train tracks, as well as the increased security along the U.S. border, has made Mexico become a new destination country for migrants.

Rudi Solaris left his native country of Honduras because his coworkers tried to kill him. The 27-year-old former cop joined the police force in search of a steady income and better life for his family. Instead, his workplace became a decade-long nightmare that offered no escape.

Solaris’s story begins in the small city of Choluteca, a short drive from the Pacific coast in southern Honduras, and ends in the industrial city of Monterrey, Mexico, over 1,500 miles to the north. The youngest of seven children, his mother died young, and at age 14, like many young Hondurans from the countryside, he left for the Honduran capital of Tegucigalpa in search of work to send money home.

As a young teenager alone in Tegucigalpa, Solaris found work in construction sites. He joined the police force at age 17 and quickly discovered to what extent organized crime had infiltrated Honduran law enforcement.

“At least half of Tegucigalpa’s police work with gangs,” Solaris said.

Honduras currently has the highest murder rate in the world, a phenomenon created by drug violence and police corruption. The security situation began deteriorating in 2009, when the military ousted former president Manuel Zelaya from office. Mexican drug cartels took advantage of the region’s instability by working with Honduran gangs, like the Mara Salvatrucha, to ship drugs arriving on the country’s sparsely populated Caribbean coast north towards the United States.

During his 10 years in the Honduran police force, Solaris learned firsthand about this reality. At one point he was assigned to work as a prison guard, a post which he held for several years. One day, an official informed Solaris that he would be sent away for several days to guard a prisoner. Solaris says that Honduran prisoners with money to bribe officials can do anything, even leaving the prison for short periods.

When Solaris escorted the prisoner outside of the jail a car awaited him. Two men inside stripped him of his weapons. Solaris soon learned that the prisoner was part of a powerful gang, and his role was not that of a bodyguard, but a bargaining chip in a deal to release the prisoner on a brief visit home on the condition that both men would be returned to the prison promptly. The men drove Solaris into the mountains outside Tegucigalpa where he spent three days in a large house complete with armed guards.

“They told me that if I didn’t try to escape, everything would be okay,” Solaris said. “I spent three days there, and I was so afraid that I didn’t sleep the whole time.”

As Honduras continued to destabilize from 2009 onward, Solaris’s job became more dangerous. On one occasion, many officers simply received notes saying they would be killed if they didn’t begin working for the gangs. One by one, Solaris watched other officers disappear. Eventually, he said that uncorrupt police banded together for protection and moved into a dormitory located within Tegucigalpa’s police headquarters.

“I only left the building to work,” Solaris explained. “It wasn’t safe outside without other officers. I couldn’t have a normal life,” he lamented. “I’ve never even had a girlfriend.”

Solaris lived in fear. One day during work, he witnessed an arms deal between several members of the police and a Mexican gang involved in the drug trade. The next day, he received a death threat because of what he saw. He locked himself in his room for two days with several automatic rifles waiting for assailants to begin shooting through the door. To save his life, Solaris fled from Tegucigalpa, hoping to reach the United States and apply for asylum.

At the Guatemalan border, Solaris boarded a bus to northern Mexico but was arrested at an immigration checkpoint and deported back to Honduras. Solaris turned around and headed north again. Many Central Americans journeying towards the United States utilize Mexican freight trains to avoid vigilant immigration officials. On his second attempt, Solaris decided to ride the trains.

Only a small percentage of migrants who brave the trains actually make it to the United States. Marauding gangs, and even corrupt cops, are known to extort, beat, rob, and rape migrants on board the trains. Others are kidnapped and held for ransom, or enlisted to work with the drug cartels.

“None of that worried me, though,” Solaris said. “Considering where I came from, the train seemed like paradise.”

Solaris made it to Tochan, a small migrant shelter in a working class Mexico City neighborhood whose name means “Our Home” in the Mexican indigenous language Nàhuatl. Today, Central American migrants fill Tochan. Most say they didn’t want to leave their countries, but after suffering from gang extortion and the death threats that came when they couldn’t make the payments, they had no choice.

Although many of the newcomers who arrive at Tochan’s doors were originally bound for the United States, they eventually apply for asylum in Mexico. The lucky ones succeed in getting temporary resident papers that allow them to work. However, even those with strong cases are usually denied and must eke out a living in the informal economy as undocumented workers in Mexico.

Solaris and another Honduran found work in a factory outside Mexico City that produces Chinese fortune cookies. Almost five months passed before Solaris received temporary residency. When he obtained his papers, Solaris took a bus to Monterrey in north Mexico. Finally, he could ride on a Mexican bus without fear of deportation.

Monterrey is a sprawl of factories producing goods for multi-national corporations that are exported to the Unted States. Four-lane highways and strip malls with Pollo Loco’s and other fast-food joints fan out from the city center. Located just over 100 miles south of Texas, here you can almost feel the U.S. influence dripping downwards from the nearby border.

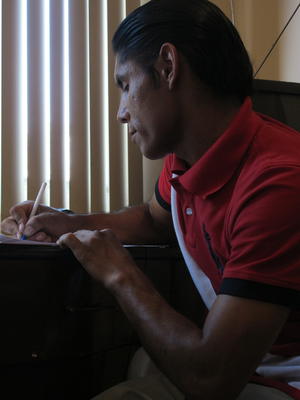

Today, Solaris shares a shabby apartment in Monterrey with a Salvadoran migrant. Each morning, they awake at 4 a.m. and leave for work at a nearby factory sorting potatoes. Sometimes, their shift lasts 18 hours straight.

Solaris’s roommate, Douglas, left El Salvador for the United States five years ago. He crossed the border, but was arrested by immigration, held in a detention center for two months, and deported. Frustrated by the lack of economic opportunities in El Salvador, he headed north again.

“I was traveling towards Arizona on my second attempt,” Douglass said, “but I got on the wrong train and ended up in Monterrey. I found a job and have been here ever since. I can send a little money home to my wife and children. It’s not as good as I’d be making in the United States, but every bit helps.”

Current immigration reform proposals include vast provisions for sealing off the border with Mexico. But until the violence associated with the drug trade subsides, Central Americans will continue to flood north. If they don’t make it to the United States, they will stay in Mexico, creating a new generation of undocumented migrants.

In the current bill for comprehensive immigration reform that recently passed the Senate allocates roughly $40 billion for an increase in border security that includes doubling the Border Patrol to 40,000, as well as adding 700 miles of fencing and aerial surveillance drones. The bill may make it more difficult for migrants to cross into the United States, but it won’t mitigate the violence in Honduras, which will continue to push migrants from one danger zone to another as they try to cross the violent Mexican border in a journey that has become more high-stakes.

Solaris has a cousin who spent three years working at the same potato factory in Monterrey. He saved money and invested it in a coyote, or, people smuggler, who brought him to New York City.

On a recent trip to Monterrey, I asked Solaris if he planned to do the same.

“Not anymore,” Solaris said. “All I want is a job. I just want to be safe. Here in Mexico I have that.”

Levi Bridges is currently spending the year in Mexico City on a Fulbright grant in creative writing to begin work on a book about the life experiences of Latin American migrant workers. He writes at bridgesandborders.com.