“They always send a working class boy to do the killing,” commented West Londons warrior-poet Elvis Costello on his lyrics to "Oliver's Army"—and you'd be hard pressed to find a starker example of this axiom than in Colombia. Like many countries in Latin America, Colombia has compulsory military service for all young men at 18 years of age. Unlike other Latina American countries, it has an ongoing civil war.

The dynamics of conscription reveal much about Colombia. For example, those with a high school diploma are only obligated to serve one year, while those without serve 18-24 months. Upon completion of your service, you are issued with a libreta militar (military card), without which you cannot own property, graduate from university, enter into a professional contract, or stand for office; as a deserter, you enter into a sort of 'civil death.' However, if you've got the money, you can buy a libreta militar, a process so common amongst Colombia's upper-middle classes that it is assumed to be legal (it is not). For example, the sons of ex-President Uribe, he of the “Strong Hand, Soft Heart,” did not serve in the military.

Within the military, too, “military service” can vary: in 2002, Francisco Santos, cousin and political enemy to the current President, commented, “the poorest of the poor do the fighting, and the rich people drive the generals’ cars, if anything” (though what he has done to rectify this situation in the 12 years since, is a mystery).

I can only comment of my own experience in combat zones and army bases around Colombia's Caribbean coast, but this delineation between the military service of the poor and that of the rich is most obvious in the army's racial make-up: Afro-Colombians at the more dangerous forward bases in jungle, and whiter Colombians serving in the well protected bases near urban centers—a reflection of the socio-economic disparity played out along racial/regional lines.

Meanwhile, illegal recruitment practices are rampant, most notoriously through the practice of the batidas (round-ups), where an army truck, often with the (illegal) assistance of the police, will turn up in public gathering spaces—bus stops, market places, busy corners, invariably in poor neighborhoods—and demand to see the libreta militar of young men. If they cannot produce them they are put into the truck, and taken to be signed up. Another practice is the use of roadblocks along important roads: in Urabá, the road between Turbo and Medellin is notorious for having regular military stops where all the young men on public buses have their libreta militar's checked, and if they don't have them they are taken to a nearby field for a cursory medical check up in preparation for their no-doubt glorious military careers.

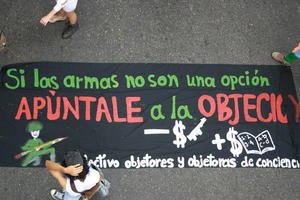

There are valiant Colombian groups promoting and defending the rights of conscientious objection—recognized under both international law and Colombian law—but so far officially only one conscientious objector has been recognized by the state, a 7th Day Adventist who applied on religious grounds. The Collective Action of Conscientious Objectors (ACOOC), who FOR Peace Presence accompanies, stage nonviolent protests (where they are regularly tear gassed), provide legal aides, and accompany conscientious objectors both physically and politically. Nonetheless, the conscientious objectors face both physical violence and deliberate harassment by the armed forces, as explained here by conscientious objector José Luis Peña Rueda, as have the solidarity activists, who have faced legal threats and threats on their lives from paramilitary groups such as the Aguilas Negras.

There are myriad other issues which stem from and play into the issue of conscription in Colombian society: the bankrolling of the Colombian military by the U.S. government, the militarization of everyday life in Colombia, the criminalization and brutalization of peaceful protests, gender discrimination and a culture of machismo, a national trauma which is passed on like an inheritance, and the basic fact that the National Forces focus on protecting multinational interests at the expense of the wellbeing of the Colombian citizenry.

In effect, the Colombian State is ambushing teenagers in poor neighborhoods and drafting them into the army with no respect for their civil rights—the right to freedom of conscious for example, or freedom of movement. It is not only callous and barbaric, but also compounds the inequalities already experienced by the majority of the population in the 7th most unequal country in the world.

Access to education, access to jobs, racial privilege—these advantages are enjoyed by a tiny subsection of Colombian society, while the teenaged sons of the majority of the population are forced to put their lives on the line to protect these privileges that they themselves do not enjoy. There are few clearer examples of structural violence along class lines than the forced recruitment of and forced labor extracted from the Colombian working classes. Elvis weren't wrong.

Luke Finn is a writer and international accompanier with Fellowship of Reconciliation Peace Presence in Colombia. He graduated from the Humanitarian and Conflict Response Institute, University of Manchester. Follow @Peace_Presence and on Facebook.