Top Obama administration officials have made much of their concern about the country’s outsized prison population. In 2015, President Obama famously visited a federal penitentiary, the first sitting president to ever do so. In 2013, then-Attorney General Eric Holder championed sentencing reforms targeting low-level drug offenders. And Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates recently announced that the Justice Department would substantially reduce its reliance on private prison operators.

But at the same time, the Obama administration has arrested and imprisoned a historically unprecedented number of immigrants for nothing more than entering the United States without the federal government’s permission. Every year, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency, a division of the Department of Homeland Security, locks up more than 400,000 people waiting to learn whether they will be allowed to remain in the United States. Even infants and toddlers are sometimes confined behind barbed wire. In doing so, it has helped to reproduce the ugly and pervasive anti-immigrant sentiment that it so often decries.

Meanwhile, the United States Marshals Service, another branch of the federal government, has quietly become a major player in immigrant imprisonment. The unit of the Justice Department responsible for custody of every person charged with a federal crime, the Marshals Service also holds tens of thousands of people in its custody while they await their trials for entering the United States without permission.

The U.S. Marshals’ actions illustrate the dual-edged sword that is immigration law. On the one hand, entering the United States without the federal government’s permission violates civil immigration law and can result in deportation. On the other hand, clandestine entry is also a criminal offense. Entering the country without permission, known as “illegal entry,” is punishable by up to two years of imprisonment. Unauthorized entry after having been deported, called “illegal reentry,” is punishable to up to twenty years. In reality, most people convicted of these crimes are sentenced to about a year-and-a-half in federal prison.

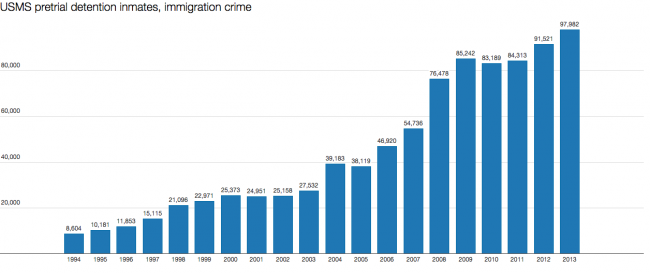

In recent years, immigration crime has become a central driver of new admissions into the federal prison system. In fiscal year 2013, the U.S. Marshals booked 97,982 people charged with an immigration crime into its custody, about six thousand more than the previous year. No other type of federal crime leads so many people into pretrial detention. This data, obtained by the ACLU through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, illustrates that these massive counts of pretrial immigrant detention is a trend long in the making. We have to go back to 2003 to find a year in which immigration defendants did not make up the largest category of federal criminal defendants to spend time in pretrial custody. The second-highest tally, for example, results from prosecutions for drug crimes. In 2013, some 28,323 drug crime defendants spent time in U.S. Marshals custody.

Even more troubling, though, is the fact that immigration crime seems immune to the constraints on pretrial detention that apply to every other type of federal crime. Since as far back as the mid-1990s, pretrial detention for most federal crimes has ebbed and flowed within a fairly narrow range, from 22,819 people suspected of a drug crime in 1994 to 34,188 people in 2010 to 28,323 in 2013.

In contrast, as seen in the chart below, immigration crime bookings have steadily increased, reflecting a decades-long decision to direct federal criminal law enforcement resources towards migration. From 1994 to 2013, the number of people confined while awaiting criminal immigration charge prosecutions jumped almost 900 percent. Interestingly, this enormous growth occurred in periodic segments. The number of pretrial detainees nearly doubled between 1994 and 1997, jumped significantly again from 1997 to 1998, and again from 2003 to 2004. Over the past decade, large annual increases have become the norm.

These periodic jumps show that expansion of immigration imprisonment is a bipartisan affair. President Bill Clinton presided over early periods of growth. His successor, George W. Bush, also oversaw large expansions of the federal penal regime due to migration-related activity. The story is a bit more complicated under President Obama. From 2009 to 2011, the pretrial detention population of immigration prisoners remained relatively steady, albeit at a historically unprecedented level of roughly 85,000 migrants facing time behind bars annually.

That pattern began to change in 2012 and accelerated the following year. In 2013, there were 12,740 more pretrial immigration prisoners than in 2009, President Obama’s first year in office, a 15% increase. This is nothing like the gargantuan growth seen over the last two decades, but it is a clear indication that life has gotten harder for many immigrants under the Obama administration.

In 2014, President Obama famously described his immigration law enforcement objectives as focused on “felons, not families.” By pitting people with criminal records against families, President Obama unmistakably suggested that his goal was to detain and deport migrants proven to endanger our communities. But during President Obama’s seven-and-a-half years in office, the federal government has regularly targeted migrants who have done nothing worse than commit the crime of entering the United States without the federal government’s permission. The end result is that today many of the federal government’s prison beds are filled by immigrants.

The legal conceptualization of illegal entry and reentry criminalizes unauthorized migration, but does little to deter it. No amount of effort will allow the United States to imprison its way out of unauthorized migration. As the legal scholar Jennifer Chacón puts it: “Would-be migrants who are undeterred by the very real and well-known threats of robbery, serious violence, rape, sexual assault, and death in the desert in the course of northward migration seem likely to give very little weight to the possibility of criminal sanctions when deciding whether to undertake the journey. Clearly, for some, the forces that compel migration are powerful enough to overcome even the most severe criminal sanctions they might face.”

Though imprisonment does little to alter migration patterns, it does impact the rhetoric about migrants and migration. Intentionally or not, using the power of imprisonment to target people for nothing more than entering the United States without the federal government’s permission frames migrants as dangerous and threatening. Trapped behind barbed wire and surveilled constantly, immigration prisoners become the symbol of danger that so many make them out to be.

If this outcome is not intentional, then Obama administration officials should quickly embrace a commitment to dramatically shrink the number of people taken into custody on immigration-related charges. If it is intentional, then the Obama administration should be held accountable for fueling the over-heated political rhetoric about migration. Either way, in its final months in office, the Obama administration could take two steps to reduce the number of migrants behind bars awaiting criminal immigration prosecutions. First, it could shut down the major pathway into the criminal court system by returning to the historical norm of prosecuting unauthorized migration through the civil immigration courts. This would have the immediate effect of turning fewer migrants into criminals. Second, the Justice Department could advise federal prosecutors to agree to migrant requests to fight criminal immigration cases from outside of prison. Allowed to unite with their families and meet freely with their attorneys rather than being in detention, migrants would be able to mount more robust defenses to criminal immigration prosecutions. That would raise the likelihood that people are rightfully convicted by law rather than simply surrendering to the prosecutor’s claims due to the trauma of imprisonment.

Neither major-party presidential candidate has indicated an interest in departing from the Obama administration’s heavy-handed reliance on federal criminal law to policing migrants’ lives. If change is to happen, now is as good at time as any to start.

César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández is an assistant professor at the University of Denver Sturm College of Law. He publishes the blog crimmigration.com. His first book, Crimmigration Law, was published in 2015.